As alarm bells ring across the country about the troubled state of Canadian media and local news, policy-makers have overlooked a surprisingly obvious and relatively accessible fix.

That local news is under threat in Canada, and with it, Canadian democracy, is not in dispute. The numbers show a sea of red ink, indicating that many Canadian media are on the financial brink.

Some of the loudest cries of alarm come from the country’s large media groups. Yet less powerful, independently owned newspapers and television stations in small and medium-sized markets face a more acute financial crisis.

A recent Nordicity/Miller study projects that up to 30 private local TV stations in small and medium markets will fade to black by 2020. These are located in cities such as Kamloops, Prince Albert, Thunder Bay, Timmins, Rivière-du-Loup, Val-d’Or, Moncton and St. John’s. When a station closes in a large market, viewers can turn to alternative sources of local news, but outside the biggest cities, losing the local television station deprives citizens of their most important source of local news. And any reader of local newspapers in smaller centres can attest to the decline in local content. As people need access to accurate and substantive information about their communities in order to participate as citizens, this decline is dangerous.

This is a big problem for Canadian democracy. It’s the subject of a major study by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. The driving cause of this crisis is changes in advertising spending away from local newspapers and TV stations and toward digital platforms, most of which reside outside Canada.

This is not the first time media in our country have faced down a financial crunch. In the 1960s and 1970s, Parliament recognized that foreign media threatened the viability of Canadian media and introduced measures to prevent advertisers from writing off as a business expense the cost of buying ads in foreign-owned publications and broadcasters at tax time.

Section 19.1 of the Income Tax Act was enacted in 1976. Its immediate result was to reduce Canadian spending on United States border TV stations by approximately $10 million dollars, about 10 percent of that year’s total TV advertising buy. Since then – and until recently – section 19 has underpinned the viability of Canadian radio, television, newspapers and periodicals, keeping Canadian advertising revenues largely in the hands of Canadian media players, who employ Canadian journalists and inform citizens in our democracy.

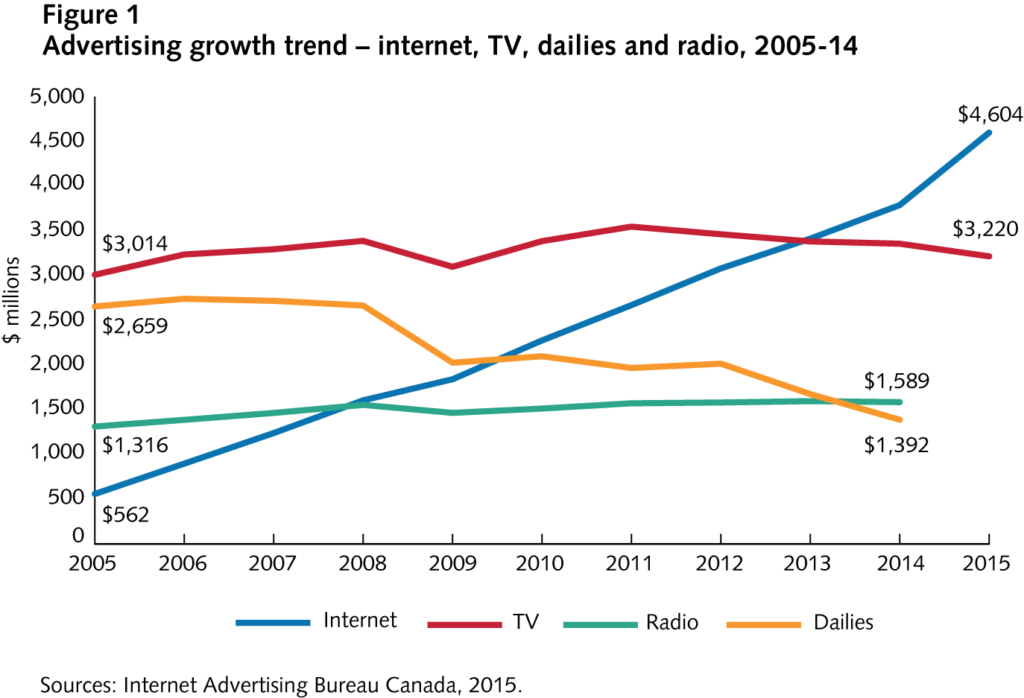

But early in the 21st century, Internet advertising began to take off in the Canadian market, growing exponentially from $562 million in 2005 to a projected $5.6 billion in 2016 (figure 1).

Based on data from the Canadian Media Concentration Project at Carleton University, we estimate $5 billion of Canadian advertising spending goes to foreign-owned internet companies such as Google and Facebook — approximately one-third of the major media advertising spend. With the Interactive Advertising Bureau projecting $5.55 billion in overall internet advertising revenue in Canada for 2016, we estimate that almost 90 percent of what Canadian advertisers spend on digital ads will leave the country.

Section 19 of the Income Tax Act provides that advertising expenses in newspapers are tax deductible only if the advertising is placed in an issue of a newspaper that is edited and published in Canada, and owned by a Canadian citizen or a corporation that is effectively owned by Canadians. Broadcast advertising expenses are not tax-deductible if the advertising is placed on a station or network whose content is controlled by an operator located outside Canada and if the advertising is directed primarily to a market in Canada.

In 1996, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) issued an opinion that a “web site is not a newspaper, a periodical or a broadcasting undertaking,” meaning that all Internet advertising was deemed tax deductible, regardless of site nationality. As is standard CRA practice, this opinion specifically left the door open to revision at some future date. It reflected the context of the early days of the Internet, when websites did not perform the functions of print media or broadcasting because of bandwidth limitations. And, of course, the only viewing platform then available was the personal computer, as mobile smartphones and tablets did not exist.

While this CRA interpretation may have been appropriate for 1996 technology, it is no longer appropriate given current practices, where content is distributed over the Internet to a wide range of devices, using a variety of technologies and program languages that enable video and audio. Whereas a 1996 website could not provide broadcasting, newspapers and periodicals, the 2016 Internet does. A new interpretation of the Income Tax Act is required— one that acknowledges this reality.

In its opinion, the CRA noted that “newspaper” was not defined in the Act. It therefore drew its definition from a contemporary version of Webster’s Dictionary, as well as a 1935 court case. Its definition of “broadcasting” derived from various references in the Act, as no other definition was then available.

Three years later, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC )— the body charged with interpreting the meaning of broadcasting in Canadian law — defined broadcasting transmitted over the internet in its New Media Exemption Order (now known as the Exemption Order for Digital Media Broadcasting undertakings). The CRTC determined that broadcasting over the Internet was indeed broadcasting, since the Internet simply represented another form of telecommunication.

Hence, the time has come for the CRA to update its interpretation and end the tax deductibility of ads placed on foreign-controlled digital platforms. This would respect the original intent of section 19 by helping Canadian media, which are essential to our democracy and our culture, when they need it more than ever.

As little as a 10 percent shift of foreign Internet advertising back to Canadian digital media would mean an influx of $500 million annually in incremental advertising revenue.

This solution has been hiding in full view in the Income Tax Act, while the local news crisis rages on. A collateral benefit of this proposal is that it would boost the Consolidated Revenue Fund by $1 billion or more annually, while also defending Canadian media and, hence, democracy.

Photo: Lars Hagberg/The Canadian Press

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.