BCE Inc. recently announced a $3.9 billion bid to acquire Manitoba Telecom Services Inc. (MTS), the incumbent telecoms provider in Manitoba. Approving the deal would solidify Bell’s dominance of Canadian markets and be at odds with recent CRTC and Competition Bureau findings that telecommunications and TV markets are highly concentrated and anti-competitive.

While the Liberal government is under no obligation to keep its predecessor’s policy, it should consider the real benefits of staying the course.

Do Low Prices Lead to Poor Quality Networks?

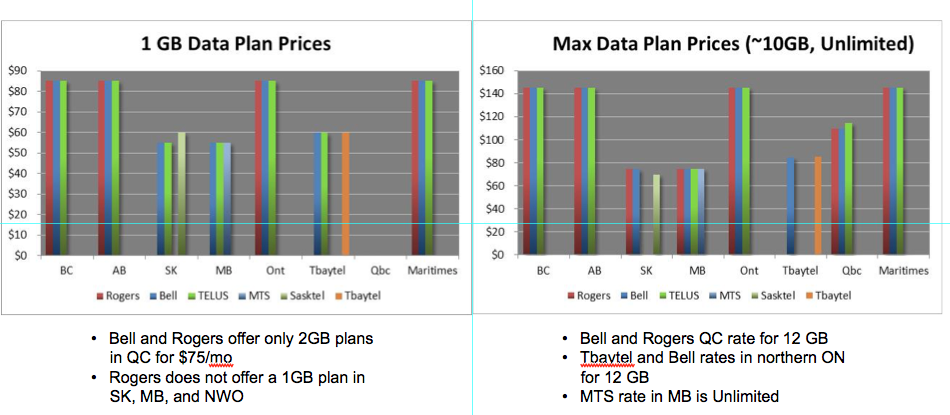

Manitoba residents enjoy some of the most affordable prices for wireless service in Canada. In BC, Alberta, and Ontario, by contrast, Bell, Rogers and Telus do not face strong rivals, and monthly rates for popular voice and data plans are $30-$70 higher than they are in Manitoba, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1: Retail Wireless Plan Prices by Province (September 2014).

Source: MTS, SaskTel & Tbaytel (2015), para 25.

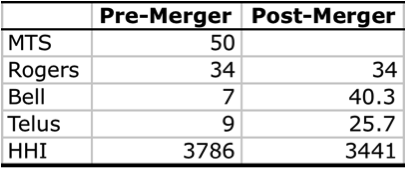

BCE’s CEO George Cope, however, contends that the Manitoba market might become more competitive, especially after Bell sells a third of MTS’s customers to Telus. Instead of two rivals (MTS and Rogers) being engaged in unsustainable price competition, there will be three strong players competing vigorously on the basis of technological and service innovation, Cope asserts (see Table 1).

Table 1: Wireless Carriers’ Market Shares in Manitoba Pre- and Post-Merger

Source: MTS (2015). Annual Report 2014, p. 7.

The regulatory economist Gerry Wall supports this line of argument, telling the National Post that “the aggressive pricing strategy has been successful in terms of keeping customers but . . . has taxed (MTS) financially – and the investment required for 4G and next (generation) networks is very challenging.” As Wall sees it, cheap prices in the short run might be costly in the long term if there is not enough money to build the 21st century infrastructure that Manitoba needs.

But is he right? In fact, while prices are low in Manitoba compared to most of the country, profits and investment at MTS are higher than Bell’s. The deal will also do nothing to change the fact that this is an extremely concentrated market.

Even these points understate the potential impact of BCE’s takeover of MTS. For instance, Bell’s plan to divest a third of MTS subscribers to Telus ignores the fact that both companies have a network sharing deal in the province. Rogers and MTS have a similar pact, but so far nothing has been said about what will happen to that arrangement if this deal goes ahead. Even if Rogers was included in a provincial triumvirate on decent terms, the cozy national oligopoly will only be expanded and reinforced.

Experience in Canada and around the world shows that having four or more rivals results in more competitive pricing, and a greater diversity of service offerings – a virtuous circle that helps reduce barriers to adoption and innovation. This is especially important since Canada ranks 32nd out of 40 OECD and EU countries when it comes to mobile phone adoption.

Profits and Capital Investment at MTS are Higher than BCE’s

Cope and MTS CEO Jay Forbes claim that MTS is being starved of investment capital because of ‘ruinous competition’ and unsustainable prices. Such claims are misleading, however, given that profits and capital investment at MTS are actually higher than at BCE, and have been for many years. BCE’s pledge to drag MTS and Manitoba out of the past and into the future by investing a billion dollars over five years to build state-of-the-art fibre optic networks, expand Bell’s Fibe TV service and increase wireless 4G LTE network coverage in Manitoba, does not entail a net increase in capital investment, but holds the line with existing trends at MTS.

In fact, MTS’s significant and timely investments in 4G LTE wireless networks, high-speed broadband, and next-generation Internet Protocol TV (IPTV) services all show that its operations compare either favourably with, or are performing better than, anything Bell offers throughout its own territories. Ninety-five per cent of Manitobans, for instance, have broadband access from MTS at 5 Mbps, which compares favourably to Bell in Quebec and Ontario, and is higher than the Atlantic provinces.

MTS’s HSPA+ and LTE wireless networks currently cover 98 percent and 78 percent of Manitoba’s population, respectively. The latter figure is less than the 86 percent coverage that Bell has achieved but this is likely due to the rural and dispersed nature of Manitoba’s population, and should be short-lived because of the step-by-step nature of major new network deployment. Indeed, MTS already plans to achieve 90 percent population coverage by 2018.

MTS also began to roll out fibre-based networks, and services that run overtop of them such as IPTV, in 2003, long before Bell followed suit in 2009-2010. Today, 70 percent of households in Manitoba can access MTS’s IPTV service, Ultimate TV, while fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) is available in sixteen communities.

Bell boasts that 7.5 million businesses and homes have access to fibre to the neighbourhood/node (FTTN) or fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) networks in its service area, and that its Fibe TV is available to 6.2 million homes. Yet, Fibe TV is available to proportionately fewer homes and take-up is roughly half the rate of MTS’s Ultimate TV (about 25 percent).

MTS has also offered smaller, more affordable TV packages for years, including some of the most popular sports channels on a pick-and-pay basis. The CRTC’s new ‘skinny basic’ and pick-and-pay TV model therefore poses few problems for MTS. Year-after-year, however, it has complained bitterly that buying high-quality entertainment and sports programs is extremely difficult. Its latest annual report noted that the CRTC had offered MTS and other distributors little protection against vertically-integrated competitors who create and own content but who charge unfair rates or block their ability to buy content rights altogether.

In short, the CRTC’s efforts have been a classic case of too little too late for smaller, non vertically-integrated companies such as MTS. Even the steps it has taken have been fiercely opposed by Bell, which has turned to cabinet and the courts frequently to overturn these moves.

Data Caps

MTS is the only operator in Manitoba to provide unlimited data plans, both for mobile and home broadband. As it boasts, its Internet and cellphone subscribers can use the Internet as much as they want without having to worry about costly overage charges.

Those days likely will be numbered, however, if BCE’s bid for MTS goes ahead. Data caps are the norm for Bell subscribers and treated as a lucrative new revenue stream and a tool to mitigate the threat that streaming services like Netflix pose to its broadcasting services. The telecoms consultancy Rewheel notes that wireless markets that go from four to three carriers usually see a steep rise in prices and a wider use of more restrictive, costly data caps.

Some Options for What Might be Done

So, if Bell’s bid to buy MTS is bad news for Manitobans, and Canadians at large, what’s to be done? Four options seem possible.

Option #1: Nothing

Accept the deal as proposed with some minor tinkering at the edges.

Option #2: The OFCOM Solution

Canadian regulators could join forces to do what the UK telecoms and media regulator OFCOM did in 2011 when faced with a reduction of five competitors to four in the UK market. In that case, when Orange and T-Mobile proposed to merge, OFCOM blessed their merger, but on the condition that the newly created firm Everything Everywhere (EE) hand over a quarter of its LTE spectrum to the number four player, Hutchison 3. It has been a vital fourth player in the UK market ever since.

Yet the chances of a new fourth player emerging in Manitoba are slim given that the most likely candidates, Shaw and Wind, showed little interest in the province prior to merging, and even less since. Moreover, pursuing such a course must account for the fact that Bell’s network sharing deal with Telus could freeze Rogers out of the market once its similar pact with MTS expires. Any conditional approval of BCE’s bid for MTS must prevent that from happening while maintaining prospects for a viable new fourth player to emerge.

Option #3: Double-down on the open access and regulated wholesale access rules while promoting Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs)

Regulators might double down on the CRTC’s wholesale mobile wireless ruling last year on concentration, while expanding it to include better access to towers, to backhaul (local and long distance connections between cellphone towers), and for Mobile Virtual Network Operators (small providers that don’t own their own infrastructure). Strict limits on the use of data caps should also be imposed.

Option #4: Kill the deal

Perhaps the most politically difficult option would be to kill the deal. This would be a prudent course to take nonetheless especially given that the remedies recently adopted by the CRTC and Competition Bureau to address the already sky high levels of concentration in the mobile wireless, wireline and TV markets have yet to be even fully implemented. To approve even more consolidation in light of such realities would be unseemly and akin to blessing bad behaviour.

That is reason enough to turn back an already dubious deal.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.