Gary Condit’s offices can be an extremely rewarding experience. Typical duties of interns can range from assisting with phones to researching legislative projects.

— U.S. Rep. Gary Condit’s official website

Filing and photocopying may not sound glamorous, but in the United States an internship can be the first step to political office. Or, as David Brooks observes in Bobos in Paradise, a post-collegiate internship unlocks the corridor to the cultural elite.

According to the Washington Center for Internships and Academic Seminars, 30,000 to 50,000 young people work as interns in congressional and government and lobbying offices in the Capitol every year. Nor is the intern phenomenon confined to K Street. Over 3,500 Fortune 500 and non-profit organizations in the United States advertise on www.internshipprograms.com, an online clearing house for intern seekers and employers. Currently there are more than 300,000 U.S. college graduates seeking internships through this service. In New York City, you can find interns working in fashion and finance and media, from Ms. magazine to National Review.

Chances are you can name at least one famous U.S. intern. But do you know anyone who has ever taken an internship in Ottawa? Or on Bay Street? Herein lies the scandal. Internships do exist in Canada, but they are relatively scarce and largely confined to the public sector. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat places interns in most federal government departments, agencies, and Crown corporations for nine- to twelve-month periods. Created under the auspices of the Youth Employment Strategy, the Treasury Board’s Federal Public Sector Youth Internship Program has sponsored 4,500 internship opportunities since its inception in 1997.

From the start of 2001 until October 1st, a total of 27 internships were advertised through the Treasury Board’s Program. During the month of September, there were 15 such advertised positions.

These low numbers should give us pause. Internships breed leaders. And in the current economic slowdown, internships provide young people with an attractive alternative to paid employment. Internships enable youth to escape employment’s version of the vicious circle: “no job without experience; no experience without a job.” As Graham Donald, executive director of the Canadian Association of Career Educators and Employers, observes, “internships offer both interns and employers a low-cost, low-risk way to arrive at a mutually beneficial fit.”

That logic evidently escapes Canadian employers. Although some large Canadian corporations, notably Nortel Networks, have introduced ambitious internship programs, smaller businesses have lagged behind their U.S. counterparts. Part of this may be explained by dissonant business cultures: Bay Street tends to reward those with the right credentials and connections; Wall Street those who have climbed up from the ground floor. But that theory only goes so far in explaining Canada’s internship vacuum. In the public and non-profit sectors, more fundamental institutional problems are at play.

Start first with the public sector. One major venue for federal government internships is the Public Service Commission of Canada (PSCC), which has employed over 5,000 students since 1980. These co-ops and paid internships are run through the Post-Secondary Co-Operative Education and Internships program, a branch of the PSCC. A small number of government organizations—including the CBC, the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency (formerly Revenue Canada) and Transport Canada—recruit interns outside of the PSCC or the Treasury Board. Still other agencies, such as the Department of Fisheries, secure additional funding for internships through Youth Internship Canada (YIC), a project of Human Resources Development Canada (HRDC).

Internships in the public sector generally fail our young people. Every one of the internship programs scrutinized in the 2001 Auditor General’s report “suffered from undue lack of precision in the statement of program objectives…” Possibly the only clear, unifying objective among public internships in Canada is a general enthusiasm for left-wing causes. The International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, a major source of overseas internships, paid for one intern in 2000 to work for the International Labour Organization, and another to work with a labour group in Peru. This taxpayer-funded organization, according to chairperson Kathleen Mahoney, last year drew on “its considerable human rights expertise, organization, and advocacy skills” to give intellectual ammunition to anti-free trade protesters in Windsor and Quebec City. Its three-day symposium in Windsor featured Noam Chomsky “and other experts.”

Canadian non-profit organizations also recruit interns. CareerEdge (www.careeredge.org) is a private-sector initiative advertising non-profit youth internships across Canada. Since 1996, it has placed just under 5,000 youths in internships at hundreds of Canadian non-profit organizations. Interns earn $1,500 monthly stipends for six-, nine- or twelve-month positions in host organizations. Some 320 non-profits participate in the program; the public sector has eschewed the service, preferring to advertise its internships on government websites and to conduct its own marketing.

A similar service is www.campusaccess.com. CampusAccess breaks down its internship offerings into separate categories. On one randomly chosen day in October, 2001, CampusAccess featured 31 Canadian non-profit organizations underwriting business and trade internships; nine organizations sponsoring medical and health-related internships; seven for technology internships; 14 for child-related internships; 55 for humanitarian and developmental internships; and 16 Canadian-based organizations offering environmental internships.

Co-op placements form another, more formalized system of Canadian internships. Predominantly technical, engineering, and accounting programs sponsored the roughly 72,000 co-op positions completed in Canada during 2000. These run for four-month periods during the course of a student’s educational term. The other major system of formal internships in Canada is overseen by the Canadian Association of Student Internship Programs (CASIP). Fourteen Canadian universities participate in CASIP, which provides 1,100 placements at salaries of around $35,000 per year. The placements are generally reserved for engineering and computer science students, and take place between the second and third years of a student’s undergraduate training.

All this sounds impressive. But when we compare Canadian opportunities to American ones, we find key differences. To be sure, comparison is tricky, owing to the blurry definition of “internship.” In Canada, an internship may mean anything from a menial summer job with a small stipend to a two-year work placement to a post-medical school posting.

One way to compare internship opportunities across countries is to collect data from private-sector companies soliciting interns in both the United States and Canada. MonsterTRAK, for example, advertises for internship, co-op and entry-level positions in both countries. This private service uses the same terminology and definitions for all advertised positions. MonsterTRAK.ca, launched last spring, is the Canadian version of MonsterTRAK.com, the largest repository of internship positions and entry-level jobs anywhere in the United States. Pierre Tison, the director of Montreal-based MonsterTRAK.ca, says the harmonized service “makes everybody’s life easier in terms of learning what’s out there for internships.” Non-profits may advertise on the service free of charge. Private companies and government agencies pay $395 to advertise a position at every school linked to MonsterTRAK.ca.

For the three-month period from August 1, 2001 to October 1st, MonsterTRAK advertised three co-op positions in Canada. These Calgarybased positions were all at the same company, Nortel Networks. By contrast, 46 internships were advertised during the same period in the United States. The difference between 46 and 3 is more than the tenfold difference in population. Consider also the wider breadth of openings on the U.S. website: They included postings in architecture, engineering, media, marketing, management, fashion and health care.

Rising Star Internships (www.rsinternships. com), another private-sector initiative, also maintains a presence in both the United States and Canada. In one week, from September 29, 2001 to October 6, the service offered 16 newly advertised internship positions (in public policy thinktanks, research institutions and advocacy organizations) across the United States; during this same period, the service did not advertise any internship positions in Canada.

The leading international website for non-profits—Action without Borders,” or www.idealist.org—lists 23,724 U.S.-based non-profits actively seeking interns but only 847 Canadian non-profits advertising for interns—less than four per cent of the U.S. figure.

Charity Village (www.charityvillage.com), which bills itself as “Canada’s supersite for the non-profit sector,” boasts tens of thousands of registered charities and non-profit organizations in its online database. And yet, over two weeks in September, 2001, it advertised just one internship position, at the Urban Renaissance Institute in Toronto. Meanwhile, over at www.usinterns.com, the U.S. analog to Charity Village, more than 65,000 internships and co-op postings can be found at any given time throughout the year.

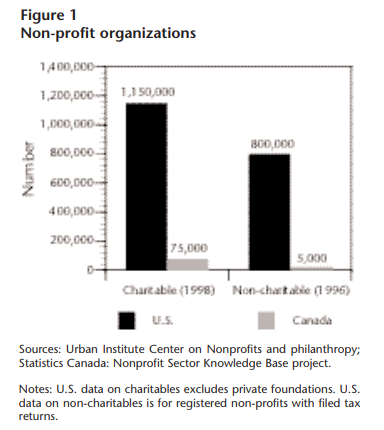

Blame Canada’s internship problem in part on a skeletal non-profit sector. According to the National Center for Charitable Statistics at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., there were 1,539,000 private non-profit organizations operating in the United States in 1998. We do not have precise Canadian comparisons. A 1997 report by the Canadian Policy Research Networks (CPRN) found scarce information on Canadian non-profits. What little information we do have, however, is revealing. As of 1999, roughly 80,000 charities were registered with the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency. (Since charities must file an annual return, a form T3010, this is a reliable figure). By contrast, there were more than 1.1 million charities in the United States. That puts the U.S. figure at 15 times the Canadian figure. But the Canadian figure is highly inflated; it includes hospitals and religious organizations, which are not included in the U.S. figure. When you correct for these differences, the number of U.S. charities is probably closer to 30 times higher than the Canadian figure.

According to a report last year from Statistics Canada, only 5,000 non-charitable non-profits had filed an annual tax return in Canada as of 1996. By comparison, the total number of registered non-charitable nonprofits in the United States in 1996 was more than 160 times this figure.

An expansive welfare state during the 1960s and 1970s led to a retrenchment by businesses and charities in Canada’s civil society. That, in turn, has led to a dearth of internship opportunities in the private sector. How, then, do we encourage more internships?

One private-sector option is to do away with special tax status for charities and non-profits altogether. One advantage of this approach is that it would cut down considerably on the bureaucracy of Canada Customs and Revenue. With fewer exemptions and lower tax rates, Canadians could then decide for themselves

which causes to support. Whichever charities and non-profits won in the marketplace of donations would have more funds to spend on causes that Canadians support, and they would consequently have more funds to sponsor more of the internships which young people desire. One advantage of this approach is that it would cut down on the bureaucracy of Canada Customs and Revenue.

To be sure, the libertarian approach may be politically untenable at the present time. It would force Ottawa to significantly re-engineer our tax laws. More ominously, it might tempt government to replace—less efficiently—those charitable causes that lost their funding. Another, even more politically improbable approach would involve weakening privateand publicsector unions, which steadfastly oppose internships. Unions also crowd out voluntary donations by shepherding forced dues toward ideologically-friendly causes.

One immediate solution in the public sector involves out-sourcing. Through initiatives such as CareerEdge and MonsterTRAK, there are significant economies of scale to be had in promoting internships via online campus networks. The U.S. public sector learned this lesson a decade ago, and its application has accelerated with the Internet. In Canada, it costs Ottawa a few hundred dollars to advertise an internship position on every campus by using CareerEdge. It costs upwards of $10,000 for the HRDC to market the same position in-house.

Neither of the above recommendations, however, should distract us from the most formidable obstacle to a healthy internship and non-profit sector in Canada: punishingly high tax rates. More money in the hands of citizens, non-profits and private companies would all significantly boost voluntary donations and internship opportunities for young people. Canada’s internship scandal is a symptom of an economy that prefers state-sponsored charity to spirited private-sector initiative. That bodes ill for the next generation of leaders.

Photo: Shutterstock