January 2009. It is my second week as deputy news director at Al Jazeera English and the war between Gaza and Israel is starting. I had become a consultant for the international network a few months before. Tony Burman, who had recruited me, was looking to restructure the newsroom in Doha, Qatar. One of the objectives was to integrate the Web platform with the television assignment desk. At the time, the two teams were not even on the same floor. During the entire month of bombing of the Gaza strip, the coverage of that conflict was all but from within Gaza. With the kidnapping of the BBC reporter Al Johnston, Gaza had become a “no-go zone,” and access via Israel and Egypt had been refused to foreign journalists. Al Jazeera was the only news organization broadcasting from Gaza along with the New York Times and a few other print media still reporting from that area.

The use of social media was limited mostly to propaganda. Organized partisan groups of both sides strove to influence public opinion using social media. The Israeli military started its own YouTube channel broadcasting clips of surveillance and airstrikes portraying its technological command of the battle space. Hamas had also sought to use the media. In Gaza, a group of Hamas fighters allowed an Algerian journalist to videotape the inside of their homemade rocket factory and spread it over the Internet. But at the end, with the foreign press shut out, scarce electricity and little Internet infrastructure, the media dynamics in Gaza centred on a handful of journalists.

That was almost three years ago. Today, technology has changed the news ecosystem, and access to information is far more widespread than it has ever been. The Ben Ali government in Tunisia cracked down hard on the media — shutting down news outlets, arresting bloggers and locking out foreign journalists. But, as the story was unfolding there Al Jazeera was able to tell and show the unrest without having one of its journalists in the country.

A video of one protest led by the mother of the young Tunisian man who set himself on fire was posted on Facebook. It was seen by the Arabic network of Al Jazeera, which showed the video of the mother on air. And by the time Mohamed Bouazizi died of his burns on January 4, 2011, protests had broken out in Tunisia and spread across the Arab world. Before many others, Al Jazeera flooded bulletins with footage, streamed online and updated its Twitter, Facebook and blog sites.

The story was not only about the power of social media but about a new collaboration between old and new media. The Al Jazeera network, for instance, broadcast images and testimonies of repression to its 100 million viewers, many in the Arab countries. It gave wide coverage and reach far beyond Tunisia. Although it took a little while, it got the attention of most media, the people and the governments across the world. Traditional news organizations broke away from the safety of their well-established reporting, using raw material from the streets. Realizing the power of witnesses of history, they had found a new lease on life by integrating that new power with their offering. Undoubtedly, this year more than previous ones, technology transformed the role of media in society.

The internet and the mobile phone have turned the news industry upside down. Less than two years ago, I was working on a television program and got bad reactions for using Skype to reach out to Canadians who lived outside the big cities where CBC had no studios. The team was thrilled to be able to get a woman who had suffered a terrible ordeal at a hospital to tell her story from her home in Peterborough via Skype. The complaint was about the poor video quality. Today, we broadcast YouTube video or amateur video covering events like the Arab Spring. The pictures are all shaky but it has greater value than professional footage.

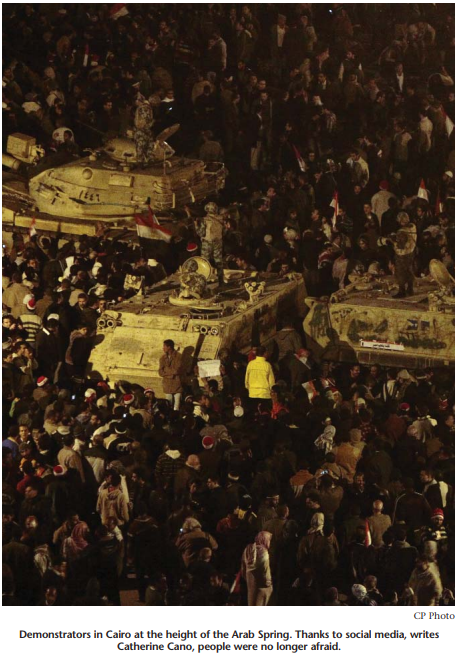

When the uproar started to reach Egypt, the people were aggressively using digital tools to communicate to the world their dissatisfaction with the regime in place. Al Jazeera, which has been reporting from Cairo since its launch, was well placed to be on top of the story. Many of its reporters in the newsroom were natives, some not much older than the Mubarak regime itself. By then, BBC, CNN and most broadcasters and news organizations were reporting the revolution and the major shift in the Middle East. Social media were at the heart of the coverage, and the merge with traditional media brought the events to a level never seen before.

Technology has changed the news ecosystem, and access to information is far more widespread than it has ever been. The Ben Ali government in Tunisia cracked down hard on the media — shutting down news outlets, arresting bloggers and locking out foreign journalists. But, as the story was unfolding there Al Jazeera was able to tell and show the unrest without having one of its journalists in the country.

The public sphere was emerging from dissatisfaction and deep frustrations. The digital universe provided a means to express it, resulting in communicative freedom. The Internet, the text messages, the photos and videos encouraged individuals to be part of a collective movement. The mass reaction to the events took the fear away. Suddenly, people were not alone and they could count on the support of hundreds and thousands of others.

Suddenly, people stopped being afraid. They saw, heard and read many more like them expressing their concerns and opposition. More importantly, citizens saw the direct impact of their actions beyond the reactions and support from Arabs and the international community. They contributed to the overthrow of both the Tunisian and Egyptian governments and wide spread protests in Bahrain, Syria and Yemen. The Arab Spring revolt saw the launch of new private newspapers and television stations and less censorship, although military police have continued to arrest and sentence bloggers to years in prison.

Since that powerful shift in the Arab countries, people across the world have continued to raise their voice. An overall sense of frustration has gone through and now beyond the Middle East, reaching other countries and continents, and for other reasons. There is a global atmosphere of dissent. Just a few weeks after the revolt in Egypt had captured our attention, a devastating earthquake followed by a tsunami hit Japan, killing almost 16,000 people and injuring thousands more. Many buildings were destroyed and worst of all, the Fukushima nuclear plant was struck, resulting in contamination and high risk for the population living around it. The impact of the leaks provoked a worldwide reaction, the strongest being in Germany. Using social media to communicate, hundreds of thousands of Germans gathered in big cities and protested for weeks, demanding an end to nuclear power plants. Chancellor Angela Merkel resisted until her party lost its stronghold in a regional election. She then reversed her position and announced she would close down the 17 plants in the country.

Across the Atlantic, other voices were raised and hundreds of worried Americans came out on the street. Most were frustrated with government and the banks that were blamed for contributing to the widening gap between the haves and have-nots.

The now well known Occupy Wall Street movement spread all across the United States and even into Canada. These protests gathered a lot of media coverage at first but did lose momentum as traditional news organizations lost interest. Using social media at first to gather strength and organize locally, the Occupacy movement has not developed into a major force yet. But it is testimony to the level of unhappiness and worry among Americans. The last three years have been dire for most, including the middle class. Many well educated professionals have had little or even no work at all during that period, living on their savings. Now, tired of the politics, they are running out of patience. The Occupy movement may not be speaking with one voice or be about one thing, but no matter what brought citizens to that level of frustration, the point is, enough is enough. And between the offand on-line dialogue and sharing awareness, this could result over time in a peaceful but lasting revolt.

There is no doubt that because of social media, citizens’ active participation in protests has tremendously increased. People can more effectively network and organize, the information spreading more rapidly and to a wider audience. As Nathan Jurgenson from the University of Maryland wrote: “With social media, people can see the difference they are making. They are not just passively consuming dissent but are more actively involved with creating it.”

The technology revolution has facilitated the sharing of information, allowing citizens to have access to more unfiltered news. It has also created many opportunities and challenges for news organizations. On the one hand, the outreach is creating real connection with thousands of citizens on any issues every day. The possibility of hearing from people on a large scale offers a better grasp of the views and reactions on any story or event. On the other hand, digital communication and the social networks also increase news organizations’ audience exponentially. But the media’s capacity to manage and to take full advantage of this new input has shrunk. Traditional media, which by all standards still attract wide audiences, are going through a midlife crisis.

Public broadcasters around the world are being challenged and cut drastically. In August, the BBC lost about 400 jobs and 1,000 more were to be cut in the next few months as a result of the merger of BBC News and World Service. The BBC benefits from big grants from the British government not comparable to the CBC in Canada. The CBC is also expecting significant cuts in its budget as part of Ottawa’s expenditure review, the Deficit Reduction Action Plan. Some critics of the CBC would stop funding it and others would emulate the donor-based PBS model, which is struggling in the United States. As for the other American networks, audiences are decreasing slowly, but decreasing nonetheless.

Objectively speaking, critics of the mainstream media — private and public — bring up interesting arguments and there might be some reason to pause and start a conversation. One can look at the way the three American networks dealt with the Arab Spring story. For the last few years, there has been little if any coverage of the Middle East. In fact, even the story developing in Tunisia was ignored for many days before journalists were assigned to cover it. Anchors suddenly showed up in Cairo but stayed no longer than 36 hours. Because of the danger in the square, most stayed put in their hotels, and rightly so. How can you suddenly claim to be experts and understand the complexities of these stories if you pay attention to them so sporadically? Without the social media, the American viewers at least would have been missing a big part of the story.

The biggest controversy by far in the media this year is the Rupert Murdoch hacking scandal. Reporters at the Murdoch-owned news properties allegedly hacked the phone messages of more than 4,000 people, including the voicemail of a 13-yearold murder victim, Milly Dowler, which set off a furious public backlash in Britain. It was also reported that a New York City police officer was approached to hack into the phone messages of American families and victims of the September 11 terrorist attacks.

Murdoch has amassed a worldwide media empire, which in America includes Fox News Channel, the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post, and hundreds of local broadcast stations and cable channels. This is a company that has a lot of control over a nation’s public discourse and although quite powerful, it has found out that it is not above the law.

Two thousand eleven was also another year of mistakes. The most embarrassing story has to be about the chastity garter belt. A new Web site in the UK called “Churnalism.com” was scheduled to launch in March. Its mandate was to help the public distinguish between independent journalists and reports that were more or less a cut-and-paste from news releases or PR work. Their research had found that half the reports were from news releases. But in the era of information overload, the founder was afraid no one would know about his new Web site. He then determined that the best way to tell people about “churnalism” was to do it. He and his team created a bunch of fake news releases and a Facebook page on a chastity belt. The story got picked up around the world by the Times of India, in Greece and Israel, as well as in the US by WGNTV in Chicago, which presented a full report.

This story demonstrates the changing newsrooms, which rely increasingly on two sources: social media and PR. According to the fourth annual digital journalism study published last March, which polled 478 journalists from 15 countries, 61 percent of journalists are citing the use of agencies in sourcing leads, making PR the dominant source for news stories.

Social media for its part is used as a tool for news gathering and verification, with nearly half of journalists using Twitter and one-third Facebook. Forty-seven percent of journalists used Twitter as a source, up from just 33 percent last year. The use of Facebook as a source went up to 35 percent this year from 25 percent in 2010. There are also risks attached to the use of social media as a source of information. It is often hard to validate its veracity. In a world where the news cycle is the next minute, it is getting more common to hear a piece of news that has not been checked or confirmed. Nowadays, some news organizations who want to stay competitive print or broadcast an unverified piece of information, warning they are in the process of confirming it.

The problem is that in our viral world, these news elements take on a life of their own, being tweeted, and re-tweeted blogged or appearing on Facebook a thousand times before they are corrected by the original news source. By then, even if it is a few minutes later, it is too late. Admittedly, it is not always a controversial news story, and more often it is just one more element in a story. At the end, we are definitively more informed but not always better informed.

A Pew Research Center survey published in March 2010 found that 37 percent of American Internet users, or 29 percent of the population, had “contributed to the creation of news, commented about it or disseminated it via postings on social media sites like Facebook or Twitter.” That was before the “like” button was integrated on Facebook, which makes it easy to share stories. We are talking about millions of people.”

In Canada, the use of social media is quite high. According to an Ipsos Reid report of a study on Canadians use of social network Web sites, 50 percent of Canadians and 60 percent of on-line Canadians have a social media profile, while 45 percent visit a social media site at least once a week. And 30 percent visit once daily. That is 35 percent and 19 percent more than two years ago. According to Steve Mossop, president of Ipsos Reid in western Canada: “While the number of Canadians accessing online social networks may be peaking, the engagement in this platform has not diminished. In fact, we continue to see dramatic increases in usage.”

Journalists are not setting the agenda any more but are part of the conversation. They do not have the monopoly on wisdom but must continue to find ways to maintain the goals of objectivity. It has become harder in a more opinionated information world. The explosion of social media in 2011 was a turning point. The Arab Spring was only the beginning.

Photo: Shutterstock