Few people will ever know who they are, but regional campaign directors are the lynchpins of modern federal election campaigns in Canada. Think of them as the metaphorical film producer, who must execute the studio’s vision with the resources provided. Regional campaign directors work with the party’s national campaign office and connect with the politicians and volunteers on the ground. During the election campaign, regional campaign directors have three principal responsibilities that, if left unfulfilled, would be disastrous for the party’s electoral performance: 1) Ensure the party has a full slate of credible, vetted candidates across the region; 2) act as a conduit for communication between the local campaign organizations and the central party headquarters; and 3) to help design, organize and orchestrate regional stops by the leader’s tour.

Filling the slate

Having a full slate of candidates is an indicator of the health of the political party. A great local candidate can add a few percentage points to the popular vote above and beyond the central campaign. A poor local candidate can drag down a regional or national campaign, particularly if there are controversies that pull the party off message. Thus, regional campaign directors are not only responsible for identifying people willing to carry the party banner but also ensuring that potential candidates will not cause embarrassment to the party due to their previous affiliations, social media postings, or other evidence of an unsavoury past.

This is why regional campaign directors work closely with local electoral district associations (EDAs) and campaign chairs to recruit and vet quality candidates for party nominations contests. The regional campaign director plays various roles depending on the specific riding in play. In ridings where the party has a willing and popular incumbent, the process is typically straightforward. In winnable ridings where there is no incumbent, the regional campaign director works with the EDA to find local notables – people with name recognition in the community and strong fundraising networks. For these reasons, successful politicians from other levels of government are prime targets for this recruitment.

The second tier of ridings is often the most difficult type for regional campaign directors to fill – those that are marginally within reach of victory for the party. This puts these seats out of reach unless a sudden local controversy or national wave of support propels the party’s candidate past the favoured opponent. Local notables and star candidates are unlikely to put their names forward for the party’s nomination given the risk involved. Regional campaign directors and local EDAs often struggle to find strong candidates as a result.

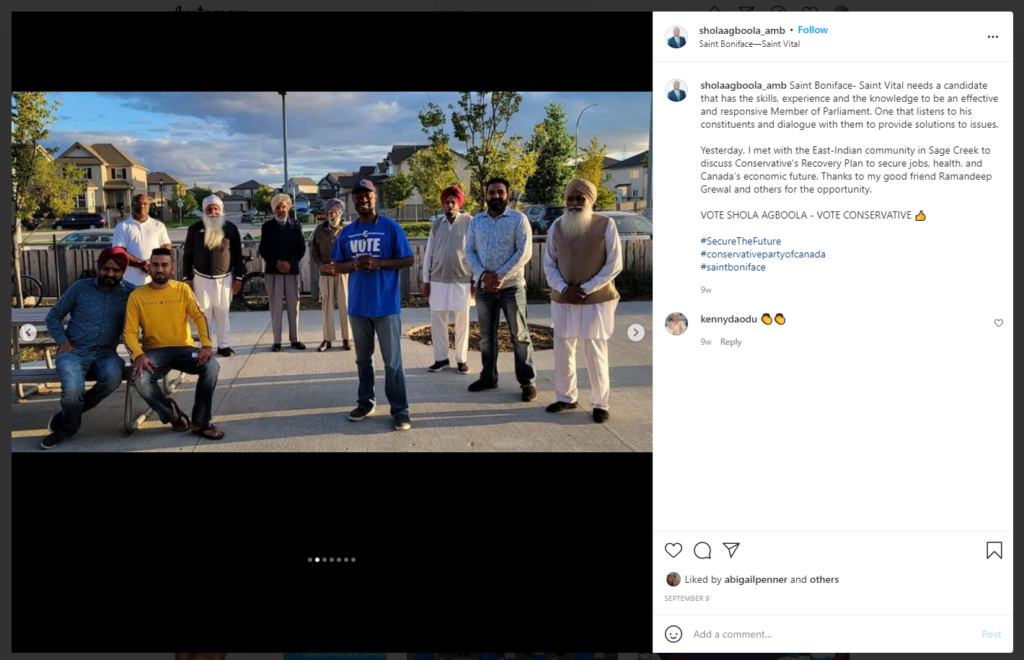

The final tier of ridings – the non-winnable seats – involve a different type of recruitment. Rather than looking for stars, the focus shifts to avoiding embarrassment. Strong vetting will ensure that these stop-gap candidates have clean financial and criminal records as well as pristine digital footprints on social media. Central party organizers offer some help in scrubbing social media accounts. As important as having a full slate is to the national image of the party, there is little the central campaign can or will do to assist the regional director with the candidate recruitment process in these difficult ridings. This work spills into the writ period, especially in the case of snap elections like the one in 2021.

Linking the centre to the local

Regional campaign directors play a limited role in defining the shape of the national strategy. Designed at the centre, each regional campaign tends to feature unique sets of policy priorities promoted by leading political personalities. During the writ period, the regional campaign director and candidates feed local priorities they hear at the doorsteps into central decision-making. Combined with public opinion data, this intelligence helps the policy and communication teams adjust messaging as necessary.

A well-functioning national campaign engages the various regional directors in this sort of strategizing. Without an integrated approach, parties may risk highlighting priorities in one part of the country that turn off voters in another. Announcements of policy promises are staged in regions where they are popular, with other parts of the platform being highlighted in different parts of the country.

This is where the leader’s tour becomes so important. Regional campaign directors have considerable responsibility for working with the leader’s advance team to identify ideal locations for the staging of events. On the ground, the regional director often drives the advance team around in search of venues that align with the chosen messaging – both in terms of backdrop, as well as in terms of hosts’ affinity for the party. This alignment is crucial. In-depth legwork by the regional campaign director may help the leader avoid embarrassing gaffes.

Once the location is set, the regional campaign director is charged with filling the location with supportive audience members. This involves calling local campaign teams and asking them to send volunteers to attend rally events or to serve as background extras in main street photo ops (for example as customers in restaurants). Convincing local campaign managers and volunteers that their time is better spent boosting the leader’s tour stop rather than door-knocking can be a hard sell. But it is a necessary part of the campaign given that the national headquarters has neither the time nor contacts to set up the regional events itself.

Despite being out of the limelight, regional campaign directors play an integral role in Canadian elections. Over time, the role has evolved to resemble that of a film producer.

Each film in production features a different cast and crew, as does each regional campaign. Every production, like every region, has its own storylines and dynamics. While the studio may attempt to package and market the film in the most favourable light, if the quality of the production is poor, it will reflect poorly on the entire organization. Casting is as important as assembling a full and competent campaign slate, just as staging a scene is as important as organizing a leader’s tour stop or photo-op. Executive producers, like national campaign managers, often get most of the credit or blame. But they rely heavily on their producers – regional campaign directors – to get the job done.

This article is abridged from a book that UBC Press plans to publish in 2022. It is part of the Inside the Constituency-Level Election Campaign special feature series.