Conservative leader Andrew Scheer has a rough few months ahead of him. Despite an increase in votes and seats, his election performance is being panned by many. He gained votes and seats while losing personal appeal and popularity – a difficult result upon which to base a “trust me” appeal to party members. Whether Scheer will last as leader until April, when the party holds a formal leadership review, is an open question.

But Conservatives need to look beyond the leader and the fresh wounds of the six-week campaign. A visceral disdain for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, combined with a hubristic belief that this election should have been won, risks blinding Conservatives in a diagnosis of what really went wrong and what must now be confronted if this regionalized, marginalized and perennial minority party is actually going to win power across the country.

Politics is a game of addition. You win by adding new voters to your coalition. So, why do federal Conservatives focus on their core vote all the time? When you turn your base from a floor into a ceiling, you will lose every election every time. Seeing politics from a “movement” perspective has you cater to “values voters” and mobilization of supporters, not adding to your overall voter pool.

In its still-brief existence as a party, the Conservative Party of Canada has won three elections and lost three elections. Its popular vote has ranged from 29 percent in 2004 to 39 percent in 2011. This year’s election garnered it a middling 34 percent, and a healthy official opposition status with more seats than in 2015.

A deeper dive into the results reveals troubling portents. This 338canada analysis pulls no punches:

Together, Quebec and Ontario hold 199 federal electoral districts and the Conservatives lost ground in 139 of them (70 percent) compared to 2015. That’s the election right there for the Conservatives. Losing ground in 70 percent of districts in the two most populous provinces in the country is a sure path to defeat.

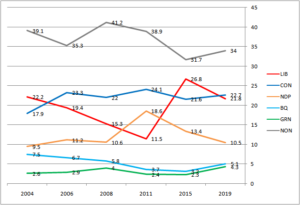

Figure 1, via CBC poll analyst Eric Grenier, shows the share of votes cast since 2004 as a proportion of all eligible voters. Conservative party support has hardly moved, making a Conservative victory exactly what it has become: a coin toss.

Share of votes cast in federal elections since 2004 as a proportion of all eligible voters

Source: CBC News

Electoral math isn’t hard; it’s just unforgiving.

Conservatism is not homogenous across Canada, but the 2003 Canadian Alliance/Progressive Conservative merger sought to mediate divergent perspectives. Unfortunately, this conciliatory strategy has been forgotten.

Following its loss in 2015, the party fell into the classic trap of speaking to itself. The 2019 campaign featured a platform and presentation that spoke mostly to voters and seats already in the bank. Its reactive policies on climate change, carbon pricing and energy reflected the dominant western conservative strain animating the party today. This strain is rooted in strong provincial conservative parties, a vigorous regional block of MPs, and the party’s recent leadership and history.

The party has failed to embrace new thinking around issues such as climate change. It failed to see the value in emphasizing health care during the campaign. It stuck instead with an overly rigid conservative worldview that left voters wondering if the party even “got it.”

The party also became blind to the political toxicity of social conservatism, at least where Conservative leaders are concerned. What any Conservative or Liberal leader personally believes, matters to voters. Scheer’s personal social conservative views on abortion, same-sex marriage, and LGBTQ rights held the party back.

This is a dilemma for principled conservatives who privilege individual liberty over collectivism and the state. But the party needs to acknowledge that the country it seeks to govern has, for the most part, come to terms with these realities, even if some Conservative members and voters have not. It is more than just not wanting to reopen debate that are politically fraught. Voters measure leaders and parties on the values they are perceived to hold on each of these issues. Scheer was found wanting.

Conservatives pride themselves as being more principled than their opponents. No virtue-signaling for them. And there is a legitimate distinction between a conservative view of the role of government, say, and the view held by Liberals and New Democrats. But the problem is this: what mobilizes conservatives does not motivate enough Canadians to win.

Meanwhile, provincial government power was being won by Progressive Conservative parties that had no problem emphasizing the adjective in tandem with the noun. Yet, an article of faith among many federal Conservatives is that progressive is “not our word,” despite many Canadians seeing themselves that way.

What Conservatives must do is make conservatism relevant to people’s lives and realistic in its approach to public policy problems. There are viable conservative approaches and solutions to climate change, income inequality, economic growth, fiscal management, health care and so much more. But they must be based in contemporary Canadian values, including compassion, to break through the voter ceiling the party has imposed upon itself.

To be fair, the party’s electoral challenges are not Scheer’s fault alone. In the short time it found itself in opposition, the party refused to appreciate that it needed to turn the page on what came before. Instead, it mired itself in political stasis, ignorant to the fact that voters change, too. It persuaded itself that the problem was one of presentation not substance. It proved to be both.

If your party platform insufficiently distinguishes yourself from your opponents, then voters are left looking at your values for clues as to whether to vote for you. Values repel, not just attract. The value proposition of the Conservative Party of Canada must become more attractive to voters to break through its self-imposed ceiling.

Unless Scheer confronts the core problems holding the Conservative party back, he will find his time as leader resembling English philosopher Thomas Hobbes’s famous description of life in medieval times: solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

Photo: Conservative Party Leader Andrew Scheer delivers his concession speech to supporters in Regina, on October 21, 2019. EPA/DAVID STOBBE

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.