Buzzwords such as livability, sustainability, mixed use and walkability are commonly used to describe the modern-day urban planning philosophy. The reality on the ground, however, is often much different and may not align with the aspirations such words reflect. In many urban areas, most growth continues to happen on the peripheries of cities, where the impacts of many of the transportation and planning mistakes of yore linger to the present day. The result — rigid zoning that discourages mixed-use development, overbuilt road infrastructure, a lack of small-scale retail and commercial development — is still leading to new communities that are largely car-dependent and create future economic and environmental liabilities for Canadian cities. How does this outcome persist despite a widely accepted urban planning approach that rejects it? Why are we — elected officials and planners — failing to achieve sustainable growth, particularly in greenfield developments where we’re starting from scratch?

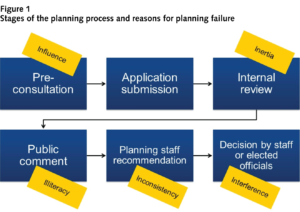

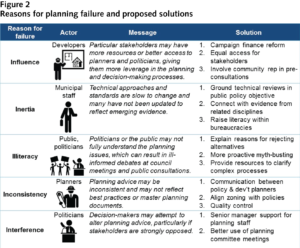

To date, critical analysis of the broader systemic challenges facing the municipal land use planning process has been limited. Identifying and acknowledging these issues would be an important first step to developing solutions. Although the reasons why effective planning outcomes may not materialize in particular cases certainly vary depending on individual circumstances, they can be summarized in five overarching themes: influence, inertia, illiteracy, inconsistency and interference, each arising in different stages of the planning process (figure 1). Elected officials, land use planners, transportation engineers and developers all share responsibility and must be aware of the ways in which they may — consciously or not — derail the planning process and propagate a failed model of urban growth. By analyzing each of these issues in turn, we can begin to identify solutions to help achieve better planning outcomes (figure 2).

Influence

The first contributor to planning failure, influence, occurs when particular interest groups or stakeholders have more resources or better access to planners and politicians than other groups, giving them additional leverage in the planning and decision-making processes. In many municipalities, it is common to hear residents say, “Developers run City Hall.” While this claim might not necessarily be accurate, there are certainly a number of practices that perpetuate this perception.

Campaign financing, for one, although not under the control of local governments, is problematic: the development industry contributes substantial sums of money to municipal campaigns. In recent municipal elections in Ontario, 54 percent of corporate contributions came from the development industry, and candidates who received contributions from the development industry were twice as likely to be elected. Although a direct correlation between campaign donations and council votes on applications made by donors may not prove causation, development industry funding is greater in municipalities where there are more projects in the approval process. Fortunately, some provinces have banned corporate and union donations, including, as of the next municipal election cycle, Ontario — an important step to removing this influence on decision-making.

Even with a limited ability to contribute to municipal campaigns, developers and lobbyists often retain greater influence due to the access they are granted to planners and elected officials. As regular fixtures at city halls, these stakeholders have professional expertise and time to dedicate to specific projects. On the other hand, residents and community organizations are at a disadvantage, operating on a volunteer basis with limited available time and few resources. Not only can this imbalance impact political decision-making and public service advice, but it also erodes public trust in the planning process, leading to the belief that the scales are tilted.

Both elected officials and planners ought to be conscious of these imbalances and reflect on their implications. Planning departments must take steps to rebalance the scales by providing more opportunities for community groups to participate in development approval processes. For instance, the City of Ottawa has introduced a preconsultation pilot that allows a community representative to participate in confidential preapplication meetings with developers. Although the community representatives must keep proposal details under wraps, the process becomes more inclusive because resident representatives are involved from the outset, are granted an opportunity to influence discussions and become able to better understand how planning decisions are determined.

Inertia

Technical requirements also pose a potential obstacle to achieving good planning outcomes. The second reason for planning failure, inertia, covers outdated technical approaches and standards, many of which have not been updated to reflect emerging evidence.

Roadway standards are one example. Even in the face of a demonstrated link between wider lane widths and higher crash rates, transportation officials and the standards to which they pledge fealty have been slow to respond. Meanwhile, the efficient flow of private motor vehicles is often prioritized over transit, walking and cycling, undermining broader municipal public health, economic and environmental objectives. Furthermore, technical standards are often based on risk analyses that ignore the risks arising from public health and environmental impacts.

The good news is that change is afoot. The work of the National Association of City Transportation Officials to develop standards that take account of wider policy objectives is gaining support, and cities such as Ottawa are widening their transportation “level of service” lens to include more sustainable and less polluting forms of transportation.

A second example is the use and planting of trees in urban settings. While a technical standard may require that trees be planted at a minimum distance from a roadway to maximize their lifespan, rigidity in the application of that standard ignores the significant role of trees in slowing traffic, storing carbon, improving aesthetics or incentivizing pedestrian travel. For this reason, technical analyses should be grounded in larger policy objectives. Better articulation of the links to relevant evidence from other disciplines could help build broader support for planning recommendations. Planners are well positioned to champion the reform of rigid technical standards within municipal administration and advocate for approaches that more effectively address the challenges of 21st-century cities.

Illiteracy

A failure to raise public literacy on planning issues can contribute to less informed debates at council meetings and public consultations. Illiteracy often manifests itself in various forms of urban myth: more traffic lanes will reduce congestion; density is undesirable; hedges breed mosquitoes. Experience shows that public opinion and emotive responses on such issues may sway elected officials to adopt positions that may not be grounded in evidence. In order to counter these tendencies, planners must effectively communicate project objectives and anticipated outcomes in plain language while addressing underlying fears and concerns. A meeting format known as deliberated consultations, which provides opportunities for the public to hear from experts, weigh the costs and benefits, and discuss options in round-table groups, has been shown to lead to more evidence-based outcomes.

A greater focus on early outreach is needed. While planning reports and committee meetings provide opportunities for planners to promote their position and outline supporting evidence, these stages of the planning process often come too late to influence public opinion. It would be helpful if planners adopted a more proactive role to dispel common misperceptions associated with urban development. Ongoing efforts to spread information should capitalize on visual mediums of communication such as infographics and short videos. Effectively communicating complex ideas in ways that are both visually appealing and accessible is essential to attracting an audience and generating interest.

For more dedicated residents, municipalities can offer workshops to help citizens understand planning processes. Elected officials, city managers and senior management could also benefit from these intensive and interactive sessions, which could ignite discussion on key challenges within the bureaucracy. Another useful approach is to move toward translating dense, indecipherable zoning codes into plain language, with simple graphics and annotations. The public is clearly interested in urban development, and planners should take advantage of this curiosity by seeking out new opportunities to convey their extensive knowledge to residents.

Inconsistency

As much as planners are making strides to improve public understanding of their work, there are instances when planners themselves fail to follow best practices. The fourth challenge, inconsistency, arises when citizens and officials see conflicting or unpredictable planning advice that may not reflect best practices or when approaches to individual applications do not evenly apply the principles of master planning documents such as Official Plans.

Municipal planners are charged with providing elected officials with independent, professional advice. Even when faced with external pressures and legislated timelines, planners must remain accountable to their profession and, in the case of government planners, must act in the public interest. And yet, recommendations to council to approve applications that fail the test of good planning practice — such as set-back single-storey retail with expansive streetfront parking lots in areas planned for pedestrian-oriented mixed-use development — are unfortunately not rare in Canadian municipalities. Planners need to acknowledge and confront poor planning practice in their profession.

Solutions to improve outcomes could include establishing clear, public criteria to be met when planners recommend approval of planning applications that require Official Plan amendments; the criteria used now are not obvious in most municipalities. A second fix is improving coordination between policy planners and the development review departments in city bureaucracies: there is often a divide between those who devise the plans and those responsible for applying them against development applications. . Lastly, planning departments should consider peer quality control mechanisms, to challenge planning recommendations before they reach the desks of busy senior managers who may not have the time or detailed file knowledge to effectively evaluate planning reports.

Interference

Finally, interference by elected officials in planning processes can derail good planning outcomes. Decision-makers may attempt to alter planning advice, particularly if stakeholders are strongly opposed. Two forms of interference may occur. The first is legitimate: the rejection of planning advice at committees or at council. Municipal councils are entrusted to make decisions on behalf of their constituents and have every right to reject planning advice. But addressing influence and illiteracy can reduce the likelihood of planning recommendations being overturned by elected officials.

The second form of interference occurs when political pressure is brought to bear on planning recommendations during the report-writing stage. Municipal organizational structures must prevent politicians from intervening here in order to ensure that the advice to council is not tinged with political considerations. The public service adage “Courageous advice, loyal implementation” applies well to how the planning function ought to interact with the political level. Political interference in planning recommendations can seriously compromise the quality and impartiality of professional advice being provided to council and the public. When it occurs, it becomes essential for senior management to protect the independence of staff, while elected officials need to respect the professional role of planners in word and deed.

Acknowledging these five major causes of planning failure — influence, inertia, illiteracy, inconsistency and interference — is an essential step toward achieving sustainable growth and better planning outcomes. While it is always tempting — and more fun — to focus on planning success, meaningful dialogue on the reasons for planning failure will enable the identification of potential solutions and strategies to improve planning processes. Cooperation from all actors is necessary to overcoming these five challenges; however, elected officials need to play a leading role to ensure public trust and city building that maximizes the value and benefits of professional planning.

Photo: Shutterstock, by Anton Gvozdikov.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.