Like a number of other advanced economies, Canada is nearing the end of peak central bank rates. (U.S. peak rates may last longer and Japan is a clear exception.)

Strong expectations are building of significant rate cuts beginning in June or July with inflation falling to just below the upper end of the Bank of Canada’s (BoC’s) target range and in light of anemic Canadian private sector growth for more than a year as of May 2024.

Yet, despite these projected declines starting mid 2024 for the BoC and later this year for the Federal Reserve Board (Fed), policy rates are very unlikely to reach the ultra-low rate levels of the 2010s when the reductions are completed.

Greater structural inflation and borrowing demand will keep Canadian and U.S. rates higher for longer in the mid-2020s.

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem’s clear guidance is that Canada is unlikely to see a return to pre-COVID-19 rates. In former governor Mark Carney’s view, pending central bank rate cuts generally will be “slower and shallower.”

We expect a central tendency for BoC rates of three to four per cent in the mid-2020s within a broader range of two to five per cent over the economic cycle.

Projected rate cuts will provide some crucial relief for homeowners renewing mortgages and businesses with floating rate debt. However, homeowners, businesses, markets and governments will need to find ways to cope with these higher-for-longer rates relative to the 2010s.

The two phases of higher for longer

The first stage of the fundamentally different policy path for the BoC, the Fed and other major central banks (excluding Japan) occurred from mid-2022 through at least May 2024.

These leading central banks reversed their near-zero rate stances of 2020-21 when they recognized that inflation’s surge during 2021 and the first half of 2022 was neither temporary nor transitory.

Rapid monetary restraint was essential to prevent global and Canadian leaps in inflation during that period – caused by extreme supply shocks (COVID-19, then the Ukraine war) and policy-driven demand from massive monetary and fiscal support in 2020 and 2021 – from becoming a future wage-price spiral.

In Canada, the consumer price index (CPI) in June 2022 was 8.1 per cent higher than a year earlier and inflation expectations for firms and households were rising rapidly.

The BoC’s rapid shift to monetary restraint was clear in hiking its policy rate from 0.25 per cent in January 2022 to five per cent in July 2023. It has maintained this five-per-cent peak through at least May.

Successful monetary tightening by early 2024 was evident in the 4.75-percentage-point increase in nominal rates and the 1.5 to 2.0 percentage-point-plus increase in inflation-adjusted (real) rates from mid-2023 onward. It caused excess demand in the Canadian economy to dissipate and the annual CPI inflation rate to fall to 2.7 per cent in April.

Supply shocks and macroeconomic policy shift

A range of structural factors has fundamentally changed in this decade from the late 1980s-to-2010s era of disinflation and the low or negative real interest rates of the pre-COVID-19 decade.

For the BoC and most other central banks, the second stage of higher-for-longer rates will likely include substantial cuts in 2024 and 2025, but to levels well above the 2010s.

Structural changes pushing worldwide and Canadian trend inflation rates higher this decade begin with the turnaround of the global labour market from large excess supply in the late 1980s to 2010s to tightness in the early 2020s.

The globalization of key goods sectors has been partially reversed as geopolitical changes and supply chain resiliency needs have fueled “friend-shoring” and “near-shoring.”

These and other fundamental supply shocks – such as catastrophic weather events and shifts in the demand for and supply of energy and other key natural resources – are raising input costs and consumer prices.

For real rates, the shift of macroeconomic policy in the 2020s from easy money and constrained fiscal policy during the previous three-plus decades bears emphasis. Monetary policy normalization since mid-2022 is critical as monetary approaches materially influence real rates.

Enormous fiscal support during COVID-19 and the pandemic restrictions in 2020 and 2021 was a sea change for governments in Canada, the U.S. and Europe.

Fiscal stimulus led by the U.S. continued in 2022 and 2023, albeit with smaller increases in Canada. Notably, combined spending by Canadian governments rebounded again in 2024.

Looking ahead at inflation’s prospects, a recent analysis of global labour markets highlighted the greater resilience of demand for and the lesser supply of workers in the early 2020s, with resulting pressures for higher wages.

Research has also spotlighted the inflationary effects of rising long-term demand for services given this sector’s stickier prices from causes such as greater labour intensity in supply.

Climate change’s effects have boosted inflation already this decade and will have an increasing impact, unless there is huge progress in climate adaptation and mitigation.

Importantly, generative artificial intelligence, quantum computing, 3-D printing and other technology advances are disinflationary. However, in our view, they will only partially offset the inflationary pressures from ongoing supply shocks and other changes.

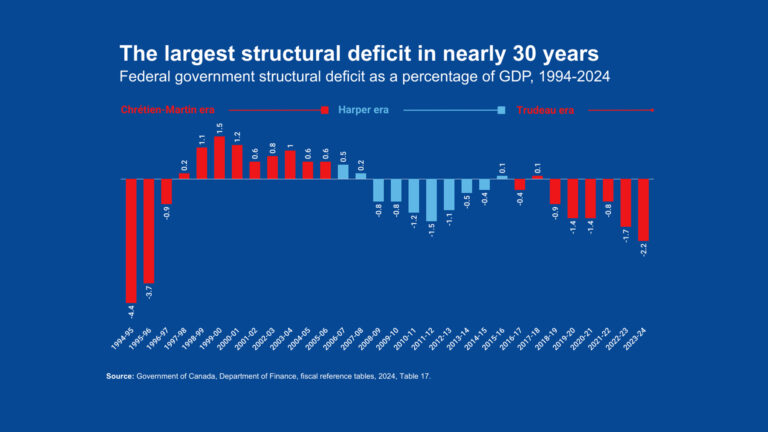

Far greater demand for funds this decade, combined with the reversal of the global savings surplus, will increase real rates in the mid-2020s and likely beyond. Government debt and deficits skyrocketed during 2020-21. Despite lesser deficits in 2022-23, most countries show few prospects of returning to balance.

Pressures for greater government spending to address health care and infrastructure capacity were serious before COVID-19, and have escalated significantly in the wake of the pandemic.

Increasing population growth in the U.S. and especially in Canada, as well as sharply rising defence spending commitments globally, are exacerbating these pressures. Real rates will also be increased by the massive funding needed globally and in Canada for climate mitigation and adaptation.

Impacts and risks

The expected rate cuts this year and likely next year will help households and firms with floating-rate debt. Yet, higher-for-longer rates this decade have already forced painful adjustments for many households, businesses and markets, and will continue to do so.

Household indebtedness soared in the era of ultra-low rates and easy money policy.

Looking ahead, Canadians will need to be much more careful about borrowing. The tough lessons of surging mortgage payments for many households since mid-2022 make more consumer prudence vital in incurring future debt and managing existing obligations.

For markets, lower policy rates will help support Canadian equities, debt and housing prices. However, the adjustment in alternative investment assets, especially for commercial real estate, with higher rates from mid-2022 onward is far from complete.

Structural factors such as hybrid work have transformed commercial real estate occupancy and demand, making it unlikely there will be a return in the mid-2020s to the pre-COVID full office workweek. The sector’s financial vulnerability merits caution even though it will vary significantly by building quality, location and age.

For governments, public debt costs rose significantly from 2022 onward. The jump in cumulative deficits during 2020-24 has led to higher-for-longer borrowing costs.

The importance of restoring federal and provincial borrowing to a sustainable path – despite increasing climate, defence, health, infrastructure and other needs – is difficult to understate. Federal debt service costs in the next fiscal year alone will exceed the cash component of Canada health transfer payments to the provinces.

For the BoC, staying the course with policy normalization, especially with meaningful positive real yields, is imperative during its pending rate cuts.

Canada needs to avoid the ultra-easy policy stances that fueled excessive demand for housing three times during 2002-22, as well as the mistakes of the mid-1970s and early 1980s of easing rates too soon after major bouts of inflation.