(Version française disponible ici)

With each budget, the Quebec government unveils its major public infrastructure priorities for the next 10 years. The 2020-2030 Quebec Infrastructure Plan was presented as the most ambitious ever. Public transit was one of the government’s four priorities (along with health, education and culture). For the first time, the plan was to balance investment in public transit with investment in our roads.

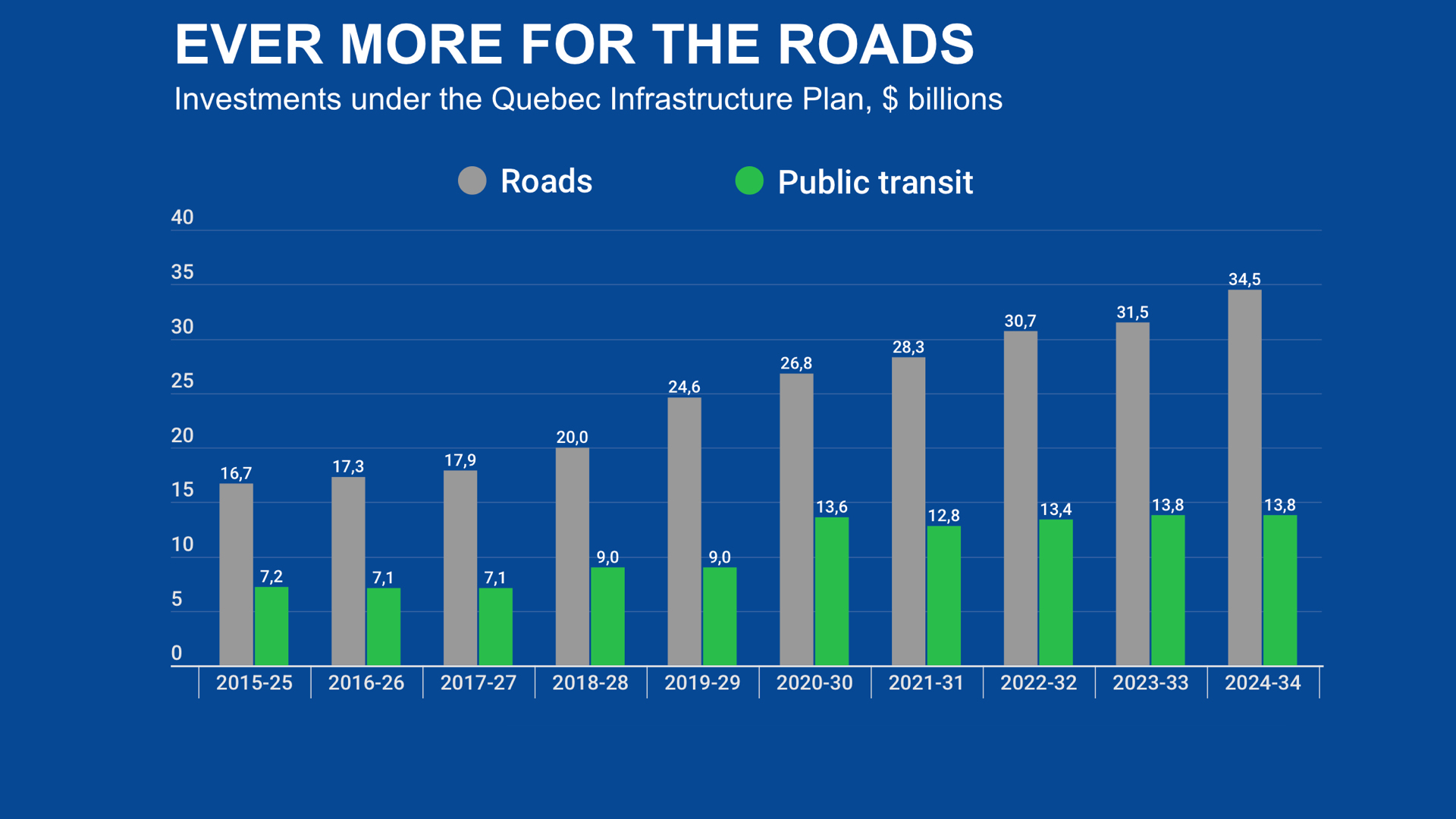

The goodwill of this proposed “strong plan for the future” did not last. After a rebound in 2020, investment for public transit in subsequent infrastructure plans have not budged, stagnating at just under $14 billion. In contrast, planned spending on roads has risen steadily, from $25 billion to almost $35 billion with the tabling of the 2024 budget. The gap is growing steadily, as figure 1 shows.

Such a U-turn may come as a surprise, but it seems to reflect the vision of Transport and Sustainable Mobility Minister Geneviève Guilbault. She recently said that managing public transit is “not a mission of the state.”

Premier François Legault followed suit by resurrecting Quebec City’s third-link project for automobiles between the city and Lévis on the south shore despite the Caisse de dépôt saying it is not supported by data. (The Caisse had been given the mandate to examine transportation in Quebec City).

Guilbault’s assertion and the premier’s persistence illustrate the dominance of road transportation in people’s habits, and ultimately in their preferences: those of economic agents (households, businesses and organizations), but also those of decision-makers. Why is there this double standard in the way transit investment is viewed in Quebec?

The problem of the ‟profitability” of public transit

There is a persistent idea that public transit is unprofitable. Yet the car is no more profitable. In fact, car transport is far more subsidized and more costly to society than public and active transit.

In the Quebec City region, for example, every dollar spent by an individual travelling by car costs society an average of $5.77. In comparison, a dollar spent on bus transport adds only $1.21 in social costs. A study published this spring for Montreal came to generally similar conclusions: the social cost of each private dollar spent on car travel is three times higher than that spent on public transit.

The financing of public transit is partly based on a user-pay system whereby one-third of the budget is provided by the user while two-thirds comes from public funds (municipal and provincial governments). Road transport, on the other hand, is essentially financed by appropriations to the ministry of Transport, i.e. by all taxpayers.

The increase in the fleet of electric vehicles poses a major challenge for the collection of fuel taxes. One potential avenue is the kilometre tax, although the government does not want to increase the burden on taxpayers.

The car, a tried and tested solution?

Many people believe the solution to congestion lies in increasing the number of highways available. However, numerous studies have shown that this reasoning does not hold water.

Economic actors adjust to the road network that is put in place: adding highway infrastructure naturally increases road use. This phenomenon of induced traffic is well-documented and well-known to town planners and urban economists. It has also been demonstrated in reverse: the withdrawal of highway infrastructure leads to the phenomenon of ‟traffic evaporation.”

Increased highway supply – and the urban sprawl it generates – entails additional costs for society. It also poses challenges for management of local public services and their funding. So far, the solution adopted by municipalities is to welcome new residents (and the property tax that comes with them), but this only postpones the problem, since the new services will also have to be financed.

A truncated justification?

To justify its road investments, the ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility produces cost-benefit analyses. In particular, it is claimed that travel time is saved, kilometres of journeys saved and human lives saved. However, such analyses overlook a number of externalities.

Highways have a negative impact on property owners living near them. Visual, air and noise pollution are reflected in property prices. Limiting negative externalities, with noise barriers for example, does not necessarily succeed in neutralizing all their effects. Road development also generates environmental costs linked to the destruction of natural habitats.

Similarly, the analysis of public transit infrastructure does not include all the externalities generated. Taking these externalities into account in the cost-benefit calculation is all the more important given the positive externalities generated by public transit.

The beneficial effects of public transit in the Quebec context

Like proximity to roads, proximity to public transit has an impact on property values. In this case, the impact is positive, as has been shown by studies looking at the impact of commuter trains and the métro, as well as rapid-transit buses and express lines.

Public transit infrastructure can also have a significant impact on structuring the urban fabric by stimulating new construction and ensuring the survival of businesses. This is particularly true in the restaurant and retail sectors, where the majority of purchases are made close to home.

Follow the U.S. lead on inter-regional bus service

Federal government must step up transit funding to cut emissions

Rural Recognition: Affordable and Safe Transportation Options for Remote Communities

High-performance rail service is a solid intercity solution for Canada

There is a common notion that a road is an investment, while public transit is an expense. This presumption is contradicted by numerous studies and is based on habits that are difficult to change. That’s why a shift is needed to offer credible and practical alternatives to the car.

Massive investment in public transit would provide a sustainable alternative to the car, as well as encourage active travel and reduce the negative externalities of highway congestion. The impact of investment in transit extends well beyond an electoral term. Decisions should reflect this reality.