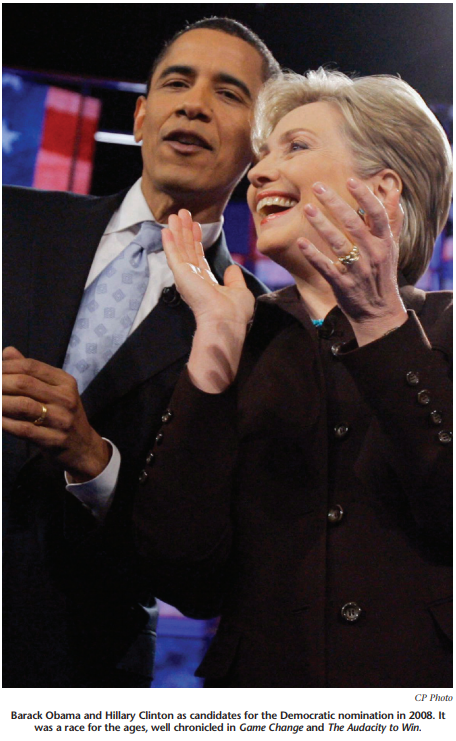

No matter the candidates, the 2008 US presidential campaign was going to be one of the most fascinating in a very long time. It was the first since 1952 that did not feature an incumbent president or vice-president, and like the 1968 campaign it took place against the background of an unpopular war. But the cast of characters that walked across the stage during the campaign made it an even more fascinating race than it was already meant to be. It included the first woman ever to have a realistic chance to become a major party nominee, the first African-American to secure a major party presidential nomination, a war hero viewed suspiciously by significant elements in his own party and an unknown woman from Alaska who, at 44, gave birth to her fifth child and learned that she would soon become a grandmother. Little wonder, then, that the 2008 campaign generated an extraordinary range of books.

Two of the best of these books are The Audacity to Win and Game Change. The former is by an insider, David Plouffe, who served as Barack Obama’s campaign manager in both the Democratic primaries and the general election. The second is by two journalists who followed the campaigns closely and had the opportunity to interview scores of people who lived it in real time. Together, the books satisfy any political junkie’s need to know what happened inside the campaigns and provide an insightful analysis of 21st-century political campaigning. Both are well written and tell compelling stories.

The story told in The Audacity to Win begins with a strategy session in October 2006 involving Plouffe, his business partner David Axelrod and Barack Obama to figure out an effective way to walk back from Obama’s unambiguous pledge nine months earlier that he would not be a candidate for president in 2008. Obama suggested a radical approach: telling the truth — that the situation had changed, and that a possibility he had ruled out in January was now something he was willing to consider. Thus began a three-month period of reflection and consultation that ended with the public announcement on a bitterly cold morning in Springfield, Illinois, that he would seek the Democratic nomination for president.

Much of the book documents how Plouffe and others built the campaign organization and developed its strategy to secure the nomination. There were primary highs — victory in Iowa — and lows — defeat in New Hampshire. There were unexpected challenges, caused most notably by the oratorical explosions of the Reverend Jeremiah Wright. There were challenges converted to opportunities, such as Obama’s highly praised speech on race given in response to Wright’s interventions in the campaign. There were triumphs — the successful European tour in the summer before the Democratic convention in Denver — and missteps — Obama’s “bitterly clinging to guns and religion” remark during the Pennsylvania primary.

For an insider, Plouffe’s account of the primary campaign is remarkably self-aware and critical. To be sure, he does not hesitate to point out how the Obama campaign outmanœuvered the Clinton campaign at almost every critical point. One of the key differences, for example, was how the two campaigns approached caucus versus primary states. The Clinton campaign seemed incapable of organizing for caucuses, while the Obama team had sufficient tactical flexibility to adjust itself to different modes for selecting delegates. Plouffe is unable to provide a good explanation for the Clinton campaign’s clumsiness in this respect, but one might speculate that Clinton’s confidence that she would win the Democratic nomination caused her to build an organization oriented strategically and tactically to fighting the general election. In any event, by the final third of the primary season the Clinton campaign had abandoned any notion of winning caucus states.

Yet, despite its strategic and tactical superiority, Plouffe is quite candid about the shortcomings of the Obama primary campaign. A press conference intended to deflect accusations of financial misconduct with a Chicago developer was a “disaster,” and Obama prepared poorly and performed even worse in a debate prior to the Pennsylvania primary. Most famously for Canadian readers, a campaign adviser spoke imprudently to Canadian consular officials to clarify Obama’s position on NAFTA. The result was a leaked memo that made Obama’s campaign rhetoric on trade seem disingenuous.

Plouffe’s relatively candid assessment of the primary campaign is unfortunately replaced by a self-congratulatory analysis of the general election. In this part of the story, the almost flawless Obama team routs the incompetent and hapless Republicans led by John McCain. From fundraising to running mate selection to debate performance, Plouffe heaps ridicule on his opponents. He does concede a couple of errors by the Obama team in the general election: withdrawing from large, energy-filled rallies during August and allowing Obama to offer a “my resumé is bigger than hers” critique of Sarah Palin, which misfired by highlighting his own experiential shortcomings. Yet, despite a climate that greatly disadvantaged the incumbent party, the race between Obama and McCain was closer for longer than it should have been.

One of the questions that Plouffe never really addresses in his book is: Why not Hillary? Why did a significant number of Democratic operatives actively seek an alternative to the woman who was the presumptive nominee going into primary season? The answer to these questions can be found in Game Change. In essence, Hillary Clinton had two major weaknesses within her own party: her support for the Iraq war and Bill Clinton’s lack of self-discipline. By 2006 many Democratic activists simply could not accept her vote in favour of going to war. Other activists worried about the practical electoral consequences that might ensue if some personal misconduct by her husband emerged during the general election. Hillary Clinton’s support within the party turned out to be deep but insufficiently broad.

As this cast of characters suggests, one lesson of these books is that, despite talk of new campaign technologies, the core of politics remains people. Politics is labour intensive, and the personalities of its leading figures and their ability to build personal relationships and judge talent are critically important.

Like all good stories, Game Change has villains. Principal among them, ironically, are the Clintons. Neither one comes across as a sympathetic character. Bill Clinton’s performance during the South Carolina primary, in which he first let his own deeply held private and personal grievances against the Obama campaign overshadow Hillary’s message and then seemingly belittled Obama by comparing his South Carolina victory to Jesse Jackson’s success there in 1984 and 1988, was one of the lowest points of his wife’s campaign. Hillary’s inability to manage her campaign staff effectively paralyzed her campaign at times and made it difficult to frame a consistent message about why, other than entitlement, she should become the party’s nominee.

John and Elizabeth Edwards — the latter surprisingly — are also villains in the Heileman-Halperin story. They were the narcissistic candidate whose self-destructive behaviour led his own staff to contemplate blowing up his campaign, and the spouse whose positive public image masked private behaviour that Heileman and Halperin describe as “abusive, intrusive, paranoid [and] condescending.” Edwards’ narcissism fuelled his relationship with Rielle Hunter, and his abuse of “longtime aide” (actually gofer) Andrew Young to conceal his paternity of Hunter’s child is one of the darker moments in the story of the campaign. Perhaps Edwards’ narcissism was due to his wife’s derisive attitude toward him. In any event, these two Democratic power couples — the Clintons and the Edwards — come across as thoroughly unlikeable.

Although about two thirds of Game Change is devoted to the Democratic primaries, the book also provides important insights into the Republican primaries and the general election. John McCain’s extraordinarily wild ride from front-runner to dead man walking to nominee tells us much about McCain’s resilience and the inherent weakness of the Republican field. Rudy Giuliani, Mitt Romney and Mick Huckabee were all deeply flawed pretenders to the nomination who lacked any capacity to exploit McCain’s early primary meltdown. Huckabee had little money and limited appeal; Giuliani’s personal life was problematic and his position on social issues anathema to many conservatives; Romney kept stumbling into bad headlines and became defined as a “flip-flopper.” For Republicans contemplating 2012 it doesn’t appear that the field has become any deeper.

Of course, perhaps the most interesting parts of Game Change involve the selection and performance of Sarah Palin as the nominee for vice-president. According to Heileman and Halperin, the McCain campaign had always planned to “shock the world” with its vice-presidential pick. For a very long time, Joe Lieberman looked to be the name that would appear alongside McCain’s on the ticket. But his prochoice views eventually disqualified him, and McCain reached out to Sarah Palin, a name that was far from the centre of the radar. She came to the campaign with an approval rating of 80 percent as governor of Alaska, but the campaign spent less than a week vetting her as a potential running mate. More importantly, when she was thrust into the middle of a presidential campaign with no experience at the national level, the McCain camp did not really have an opportunity to prep her for the intense scrutiny and rigorous schedule she was about to endure.

In the beginning the choice appeared inspired. Palin energized the base and threw the Obama campaign off balance. Her speech to the Republican convention was a triumph: she ad-libbed her hockey moms as pit bulls with lipstick line, and she overcame a malfunctioning teleprompter that left parts of her speech off the screen. McCain was ecstatic, and Palin became the main storyline from the convention. But her weaknesses were about to be revealed in her infamous Katie Couric interview, which seems to have sent her into something like a catatonic depression from time to time during the remainder of the campaign. Although she recovered slightly during the vice-presidential debate with Joe Biden, the bloom was off the rose, especially among influential conservative opinion leaders.

As this cast of characters suggests, one lesson of these books is that, despite talk of new campaign technologies, the core of politics remains people. Politics is labour intensive, and the personalities of its leading figures and their ability to build personal relationships and judge talent are critically important. As related in these two books, fundamental character flaws in its major players — with one notable exception — deeply affected how the 2008 presidential campaign unfolded. The notable exception, of course, is Barack Obama. Although both books acknowledge that Obama made mistakes and underperformed at times, his basic character is depicted as being remarkably flawless. His only vice appears to be an inability to give up smoking, but otherwise the portrait seems almost too good to be true. One can understand David Plouffe’s reluctance to expose fundamental flaws, but the absence of critical distance from Obama in the journalistic account is a weakness. One wonders whether fear of losing access to a sitting president is a factor here.

These books are enjoyable reads that provide surprising insights into high-profile individuals and a surprising campaign. They are very much worth the time spent on them.

Photo: Shutterstock