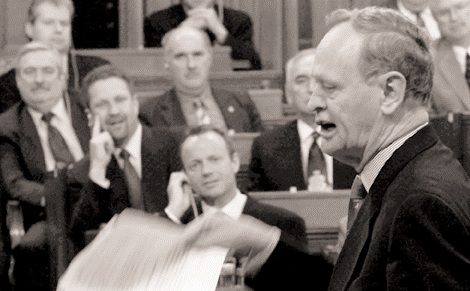

In strictly partisan terms, the Liberal Party’s re-election last November to a third consecutive majority government was a remarkable accomplishment. No federal party had won three consecutive majorities since the Liberals won five of them from 1935 to 1953, and no Prime Minister had led his party to three consecutive majorities since Prime Minister Mackenzie King in 1935, 1940 and 1945. Whatever one’s views of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, historians will be forced to give him full credit for these three majority victories.

The Liberal three-peat does, however, raise the question: Is Canada a de facto one-party state? In one sense, the obvious answer is no, because four other parties won enough seats in the House of Commons to secure official party status. And a smattering of other parties also contested the election, from the Marijuana Party to the Marxist-Leninists. We are not North Korea, Syria or Eastern Europe, circa 1970. Moreover, it took only a matter of days for the partisan arguing to resume after the votes were counted. Alliance leader Stockwell Day began telling the Prime Minister who should be dropped from his cabinet; Mr. Clark lectured the Prime Minister on a variety of subjects, sounding, if only to himself, as if the Conservatives had won the election rather than barely survived it. We can be quite sure that the partisan debate will be in full throat throughout the parliamentary session.

Partisan parliamentary debate, however, should not obscure the pertinence of the question–is Canada a one-party state? Multi-party democracy presumes that at least one party is ready and capable of replacing the existing government by winning an election. Clearly, no party was ready and capable in the last election, despite the pretensions of the Canadian Alliance. Will any party be ready and capable next time?

No one can predict the political future three, four or five years from now. There are too many unknowns for sensible prognostications. There may be changes in the Liberal leadership. We do not know how the economy will be performing three or four years from now. We cannot predict domestic or international crises that may test the mettle of the existing government.

What we can say is that none of the opposition parties–and this observation is particularly relevant to the Official Opposition, the Canadian Alliance–has absorbed the lessons of Canadian political history. The future is seldom like the past, but the past does offer clues about what it takes to be successful in Canadian politics.

The most important clue is the nature of non-Liberal governments in the 20th century. Only four of them lasted any length of time, and they all shared roughly similar characteristics. The Conservatives who defeated the Liberals these four times put together a coalition, which is what parties must do in a geographically sprawling, regionally sensitive, linguistically divided, ethnically diverse country.

The non-Liberal, Conservative-led coalitions that won did not endure more than two terms. The coalitions eventually broke asunder. They did not succeed in cohering long enough to replace the Liberals as the country’s dominant party. But they did come together for a while, and provided a temporary alternative to Liberal rule, thereby creating a competitive two-party system and forcing the Liberals to renew themselves.

These successful non-Liberal coalitions were comprised of four elements: traditional Tories in Atlantic Canada; Conservatives in Ontario, backed by Toronto financial interests; Western populists (and business interests); and, critically, various hues of French-speaking Quebec nationalists. The Conservatives formed a majority government only once without significant strength in Quebec–in 1917 under Prime Minister Robert Borden. (”Significant” means either a majority of seats in Quebec or a healthy minority of them, as in 1930 when Prime Minister R. B. Bennett won 24 seats to 41 for the Liberals.)

If history is even a crude guide for Canadian political success, it can easily be demonstrated how far the non-Liberals have been, and remain, from re-creating any semblance of the only coalition in a century that has defeated the Liberals. The Conservatives show strength mostly in Atlantic Canada. The Alliance has captured the hearts of Western Canadian populists (and significant business interests). Both have some support in Ontario, but not enough to seriously threaten the Liberals. And neither has anything remotely like a base of support in Quebec.

In other words, both the Conservatives and Alliance represent elements–but only elements–of the coalition that history suggests is necessary to threaten the Liberals’ dominance. Unless and until one of these parties, or a new political formation representing a melding of the two, begins to reassemble all the elements of the successful non-Liberal coalition, they will fail to threaten the Liberals.

There was something else about these non-Liberal coalitions–with the exception perhaps of R. B. Bennett’s. They were pragmatic arrangements rather than ideological formations. The issues of the day differed. Some of the great questions of moment, such as Canada-US free-trade under Brian Mulroney, were sharply defined. But pragmatism and brokering the interests of different regional and ethnic groups had more to do with political success than did the siren songs of ideology.

Procrustean politics does not work in Canada. Parties that try to shape the country to their message rather than shaping their message to the country–the whole country not just elements of it–are likely to lose. This is not merely the message of the past. It resonates today, witness to which are the Liberals’ three majority governments and the repeated failure of the Reform and Alliance parties to defeat them.

Procrustean politics does not work in Canada. Parties that try to shape the country to their message rather than shaping their message to the country–the whole country not just elements of it–are likely to lose.

It will be argued by those of a more ideological persuasion that what has worked for Conservative governments in Alberta and Ontario can be transferred with few modifications to national politics. Obviously, anyone on the political right will be pleased with the victories and subsequent governing approaches of Premiers Ralph Klein and Mike Harris, and perhaps very soon Liberal Premier Gordon Campbell in British Columbia, whose policies seem inspired by the Klein-Harris successes.

This is a trap into which Canadians searching for national alternatives have frequently fallen–to believe that what works in a provincial context can be transposed onto the national landscape. Conservatives chose successful provincial premiers to lead them, hoping their provincial success would bode well for the national party. George Drew, John Bracken and Robert Stanfield, estimable men all and provincially successful too, failed as national leaders to build a successful alternative to the Liberals. The same, it might be said, applies thus far to Stockwell Day, the former Alberta Treasurer supported publicly by Premier Klein.

Provinces, especially the large ones, are diverse societies. Provinces have their cleavages, but no province is as diverse as the country writ large. Provincial politics does not require (Quebec excepted) leaders with proficiency in two official languages. They do not impose on leaders or parties the need to reflect interests as diverse as those of, say, fishing villages on the East Coast, farmers on the prairies, large concentrations of multicultural Canadians in cities, and so on. They don’t demand of leaders that they play on the international stage. And they don’t require leaders or parties to handle complicated national files or craft messages that will resonate everywhere in Canada.

If it were easy to make the leap from provincial success to national triumph, you would expect Canadian politics to be full of shining examples of this. In fact, there are few. There have been successful provincial politicians who shone in federal politics, but not many of them–and none at all who tried to transfer their received wisdom gained in provincial politics into a kind of national vision. So it is a comforting illusion, but nothing more, to suggest that what has worked in the smaller theatres of provincial politics can be the script for national success. The history of Canadian politics suggests otherwise–resoundingly.

There is therefore nothing inherent in Canada that drives the country to one-party dominance. The problem, rather, is the failure of some political people to understand the nature of Canadian politics, the essence of which consists of trying to understand the whole country, not just parts of it, and to frame policies, choose leaders and craft messages that have a chance of being appreciated in all parts of Canada. It has been the consistent conceit of the Reform/ Alliance Party, born largely in Western Canada, that the essence of its message, if presented forcefully enough, with a new leader and a new party label, would finally resonate sufficiently beyond the West to bring the party to power. Having failed three times, it is now incumbent on the Alliance to step back, reconsider some of its policies and reshape itself into a more moderate, less ideological and therefore more electable political formation.

I say ”conceit” because in everything that transpired in the change from the Reform Party to the Canadian Alliance one essential ingredient was missing in the overtures to the Conservatives: a genuine attempt to incorporate core values and ideas from the Conservative Party into the Canadian Alliance. The Alliance basically said to Conservatives: ”We are stronger than you are, so join us.” What the Alliance should have done, had it been serious about attracting Conservatives or bringing about a merger of the parties, was to have studied the history and policies of the Conservative Party and identified at least some core Conservative ideas and values that could be brought into the new party. That would have been genuine co-operation rather than force majeure. The policies I have in mind are, for instance, a commitment to regional development, tolerance of abortion, and support for government cultural policies. Such an approach would have irritated some (perhaps many) Alliance members, but it would also have made the party more inclusive and therefore more electable.

What the Alliance should have done … was to have studied the history and policies of the Conservative Party and identified at least some core Conservative ideas and values that could be brought into the new party.

I realize this approach would have been difficult for another reason: that the Reform Party was born in rebellion, not against the Liberals in the first instance, but against the Conservatives. Reform grew up with the Conservatives in power in the late 1980s. Many of its core supporters were former Conservatives. There was among Reformers the belief of the righteous that they were custodians of true ”conservatism,” and that the Conservatives had lost the faith. In Alberta, to take the most obvious example, Reform decimated not the Liberals but the Conservatives. Replacing the Conservatives was therefore the first essential step to political legitimacy, but having accomplished that objective the Reform/ Alliance refused to concede it had anything to learn from the Conservatives.

We shall see in the next few years whether the lessons of Canadian political history and three consecutive defeats impose themselves on the Alliance and the Conservatives. In the meantime, we are left with another Liberal majority government and a series of questions about the health of Canadian democracy. These questions arise, not because the Liberals won, but because of how they won and what their victory revealed about Canadian politics beyond the simple failure of an opposition party to shape itself into a pragmatic, winnable alternative.

Perhaps the likelihood of a Liberal victory contributed to something that deserves more attention than it received in the immediate aftermath of the election””the low voter turnout. Obviously the health of a democracy depends on more than just tabulating the number of people who voted in an election, but that tabulation is at least an imperfect guide to the citizenry’s interest in its so-called civic society.

Only 62.5 per cent of Canadians on the voters’ lists bothered to participate in the election by voting. From 1945 to 1988, voter turnout averaged 75.4 per cent of all voters on the list. Since then, Canadian federal elections have witnessed a steady decline in turnout. Indeed, if Canadians used the US method of calculating voter turnout–those who voted compared to the total eligible population, rather than those with names on the list–the 2000 turnout would have been only 51 per cent, or about the same as we saw for the recent US elections. Canada therefore is now at or near the bottom of voter turnout for western democracies. That cannot be a healthy sign for Canadian democracy.

If Canadians used the US method of calculating voter turnout–those who voted compared to the total eligible population, rather than those with names on the list–the 2000 turnout would have been only 51 per cent, or about the same as we saw for the recent US elections.

Problems obviously exist with the new method for placing names on the voters’ list. Canada used to enumerate voters in every election. People went door-to-door across the country in a massive effort to prepare the voters’ list. In the last two elections, however, Parliament authorized a permanent voters’ list that was supposed to be updated from a variety of data bases, including passport renewals, driver’s licences, death notices, etc. Clearly, this new system has been plagued by problems, some of which were reported in the media during the last campaign. Parliament would do well to conduct a serious study of the new system during the next session and either revise the procedures thoroughly, or scrap it and return to the old door-to-door enumeration.

But the explanations for the low voter turnout obviously go beyond the mechanics of preparing the voters’ list. I don’t have definitive explanations. I suspect political scientists and others will be probing the questions surrounding the low voter turnout, and their work may help shed light on answers. Some of my speculations would include the following:

- Politics in recent years under Mr. Chrétien has become rather humdrum, which was no bad thing. For almost two decades before he became Prime Minister, the Canadian body politic had featured highly divisive issues that wound up pitting region against region and at times large elements of the Canadian electorate against the federal government. These included wage and price controls, the Goods and Services Tax, the National Energy Policy, patriation of the constitution, Meech Lake, Charlottetown, and Canada-US free- trade. Deficit reduction dominated the politics of the mid-to-late 1990s, and although a necessary and worthy subject for government attention, it was hardly the stuff of passion.

- If those who probe Canadian ”values” can be believed, Canadians have come to expect somewhat less from government. Canadians are more self-reliant than ever. Ottawa’s share of national spending continues to shrink. So if government really does mean somewhat less than before, at least some Canadians may not reckon voting to be worth the effort.

- International trade treaties have shackled what governments can do, or even contemplate. Cross-border capital movements and ”market forces” sometimes mock governments’ capacity to act. At home, the services most directly touching the daily lives of citizens–health-care, education, roads, environmental protection, policing–are provincial. The voter turnout for provincial elections has not been declining.

- We also live in the age of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which has thrust courts, and especially the Supreme Court of Canada, into the role of settling many of the most contentious issues surrounding individual or collective rights.

- We live, too, in the television age, a medium principally of entertainment rather than information. The average Canadian television set is on 21 hours a week, about the same amount of time a student is in school classes. Television has tremendous reach but little depth, and certainly in my lifetime television has changed the nature of political campaigns, political advertising and strategy, and even the skill sets required for political success. It is doubtful, however, if television has done anything to engender a greater degree of civic engagement; indeed, if political sociologist Robert Putnam’s work in the United States is any guide, television may have produced precisely the opposite effect.

There may also be a widespread feeling that Parliament has grown irrelevant. The media coverage of Parliament focuses largely on Question Period, which is pure theatre, so that what citizens see via the media likely leads them to conclude that little serious business is done in Parliament.

Parliament has always been a debating chamber, the place for robust debate and argument about the issues of the day, the challenges of the future and the legacies of the past. It has always been a rough-and-tumble place. But it is largely just that: a talking shop. Its deliberative functions long ago atrophied; its legislative function is highly scripted. There is no possibility–and I say this with considerable certainty–that anything will change under Mr. Chrétien, who has grown up in and prospered under the institutional status quo and who, as Prime Minister, greatly benefits from it.

I do not deny that within the private councils of the Liberal caucus individual Liberal backbenchers may have some influence on government policy writ large or on this or that piece of legislation. But I would suggest that their influence is limited and largely indirect, and it is certainly largely hidden from public view. True, a handful of Liberal MPs sometimes goes public with discontents. But a rule of thumb to apply in listening to such public expressions of discontent is this: Those who speak publicly are invariably those with the least influence. That is why they run to the media, because the rules of the game–the rewards and punishments for backbenchers–require effective dissent to be privately expressed.

The parliamentary system has been called an ”elected dictatorship.” One of its virtues lies in the ability of a government commanding a parliamentary majority to get things done. There is, however, something increasingly at odds between the rules and mores of this particular elected dictatorship and the way Canadian society and its private institutions operate. Successful companies long ago learned that strict, hierarchical management chains don’t work very well. Employees are not to be treated as soldiers responding to orders but as individuals with ideas and skills. Companies have frequently flattened out their hierarchical management structures to get better ”buy-in” by employees and therefore better overall results.

We also have the best-educated population in Canadian history, and education provides a sense of personal empowerment, giving people the intellectual tools to reach their own conclusion. Everything we know about contemporary Canadian society–a point drilled home by political scientist Neil Nevitte–is that we are no longer a deferential lot. We are more self-reliant, more self-demanding, more self-actualizing; and therefore less inclined to follow established lines of authority. We are also justifiably skeptical of the bombardment of advertising messages that surround us daily, so we are less impressed than ever by messages from anywhere, including government, that attempt to paint black as white. Since Parliament is a form of organized intellectual mendacity in which partial truths or selec- tive interpretations are falsely elevated to wis- dom, citizens are skeptical, even outraged, by the daily attempts to make whole cloth from ill-fitting bits and pieces. Citizens know they make mistakes in their own lives, as do the institutions for which they work; they recoil from the unwillingness of those in political life to admit error.

What we have, therefore, is a hierarchical political system in which the trappings of egalitarianism–one person-one vote; one MP for every constituency; one parliamentary vote for each MP–are mocked by the concentration of power in only a few places within the system, notably the Prime Minister’s Office and the cabinet, with few, if any, checks and balances to this power. Increasingly, the rest of society is not structured in this fashion, but parliamentary politics is, with the result that a gap of credibility, or at least of interest, grows between those who work within the political system and those who send people there.

The trappings of egalitarianism—one person-one vote; one MP for every constituency; one parliamentary vote for each MP—are mocked by the concentration of power in only a few places within the system, notably the Prime Minister’s Office and the cabinet.

We know that the Canadian Senate is hardly a check or balance, an observation so obvious and tired as not to require elaboration. We know, too, that strict party discipline in parliamentary votes robs MPs of any public deliberative function. We increasingly appreciate that courts, not legislatures, are the institutions charged with sorting out contentious issues.

We know, too, that the first-past-the-post electoral system produces parliamentary majorities–thereby encouraging the ”elected dictatorship”–while simultaneously distorting the overall voting intentions of the election. Governments arrive in Ottawa with parliamentary majorities built on only a minority of the total votes cast. The same can be said, by definition, of MPs, who are often elected with fewer than half the votes cast in their constituencies. These discrepancies produce anomalies every election for parties whose seat total and share of the popular vote are quite dissimilar. Where a party gets its votes can be as consequential for parliamentary results as how many they receive. This over- and under-representation linked to the first-past-the-post system often plays itself out with regional consequences whereby parties find themselves shut out of whole regions even though they scored a respectable minority of the votes there. Or, conversely, a party can be supreme in parliamentary terms–as the Liberals have been in Ontario””despite winning only about half the popular votes in the region.

The first-past-the-post system therefore exacerbates rather than attenuates the regional cleavages inherent in Canada, with no offsetting attenuation possible through an elected Senate, such as in Australia where the elected Upper House is chosen on a proportional representation basis. Since one of the enduring tasks of politics in a diverse country that was created as a bold act of political ingenuity must be to reconcile competing regional and linguistic claims, our political system to some extent works against this necessary objective of national governance.

No democratic country has a perfect electoral system. No sooner, for example, had our friends in New Zealand dropped the first-past- the-post system for a multiple-member constituency form of proportional representation than voices were heard questioning the wisdom of the change, since the new system almost guaranteed minority governments. The recent US election highlighted an obvious criticism of the electoral college system, which produced a president who won half-a-million fewer votes than his opponent.

If Canadian political parties were up to the task, especially those in opposition, they would spend time in the years ahead thinking about modifications to the electoral system that would make it more representative, as well as changes to the parliamentary system to make it more deliberative. Changes on both fronts might well induce Canadian citizens to reconnect somewhat to a system many of them have relegated to the margin of their consciousness. But the task cannot be left to parties alone: The political system belongs to us, not to them.

No one should believe that even the most serious reflection will move this government. Not since the 1950s has Canada seen a government that offered so little internal renewal. There are two broad ways by which renewal can occur in a competitive party democracy: either by replacing the governing party with another or by the governing party renewing its personnel and policies. Neither happened in the last election. Not only did the Liberals win, but their leader and most of their caucus won re-election. The number of new Liberal recruits was startlingly low; the recidivism rate of Liberal MPs astonishingly high.

Elections are about choices. Voters do not choose in a vacuum: up or down for just one party. They shop around, and among the options available last November the largest number of voters preferred the Liberals. None of the opposition parties, for reasons I tried to explain at the beginning of my remarks, looked fit to run the country. But in returning the Liberals, Canadians chose a party that had done almost nothing to renew itself. Under these circumstances, what ails the political system will strike those who still run it as non-existent or inconsequential. They have won again within that system and will see no reason to solicit views for change. That does not mean the rest of us must sit like mutes; indeed, it is through opportunities such as this that we can chew matters over so that when conditions are more propitious for change we will be ready with matured reflections to help improve what is, after all, a system that belongs to us, the people of Canada.

This is the text of a speech prepared for delivery at Simon Fraser University, Jan. 19, 2001.

Photo: Shutterstock