Full disclosure: I have always liked and admired Michael Ignatieff. Before he returned to Canada in 2005 to run as the Liberal candidate in Etobicoke-Lakeshore with his not-so-secret plan to run for the party’s leadership, I felt he was probably Canada’s finest public intellectual. His book and television series Blood and Belonging was one of the most penetrating and useful analyses of the forces that precipitated the devolution of state-to-state warfare into ethnocultural conflict that have ever been penned.

His defence of the decision to invade Iraq — while discredited as time passed — was elegant and provided a sweeping historical and geopolitical context that was never present in the triumphalist exhortations of other supporters. And while it was often cited out of context, his parsing of concepts such as a “moral war” and the lines between justifiable and illegal state use of force in his book The Lesser Evil: Political Ethics in an Age of Terror made it absolutely clear that you were reading the works of a superior mind.

He had held academic postings at Cambridge, Harvard and Oxford. He had been on the cover of GQ magazine. The British press had labelled him “the thinking woman’s crumpet.”

In sum, he was the total package. It was small wonder then that the three so-called “men in black” who came to visit him in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in October 2004 would see him as the ideal candidate to lead Canada’s natural governing party past its sponsorship-scandal muddle back to glory. Given his pedigree, his accomplishments and the accolades he had received throughout his career, the man himself could be forgiven for agreeing with them.

But we all know how that worked out. Michael Ignatieff did indeed go on to lead the Liberal Party of Canada — though not in the way anyone envisioned in 2004. Instead, seven years later, he presided over its worse electoral showing in a century.

Two years after that ignominous failure, Ignatieff returns with this memoir of his travails in the arena of public life. He states that his purpose in chronicling this journey is “for the young man or woman who believed in me and saw me fail. I am writing this to help them succeed when their time comes.” But in most of this thin (183 pages) tome he wrestles with a more introspective (if unasked) question: Was it something about him that led to this monumental — and uncharacteristic — failure; or is it the political system itself that is too brutish and crude to allow the likes of him to survive?

Ignatieff’s opening chapter is entitled “Hubris” and in it, he hints that the answer will be found in the first half of this question. He makes clear he wants “to explain how it becomes possible for an otherwise sensible person to turn his life upside down for the sake of a dream, or to put it less charitably, why a person like me succumbed, so helplessly, to hubris.” Ignatieff asks — seemingly rhetorically — “The idea [to return to Canada to become prime minister] was preposterous. Who did I think I was?”

The fact that this opening introspection lasts for a meagre three and a half pages, however, suggests his modesty is a tad fleeting.

While confessing that “I certainly didn’t have a good answer to the question of why I wanted to hold high office,” he proceeds to wonder if his motive might be found in family history: a father with a lineage that goes back to “minor -nobility” in 19th-century Russia and who went on to a distinguished career as one of Canada’s most accomplished diplomats; a mother who was the niece of Vincent Massey and whose roots go back to building of the CP Railway. This heritage caused him to feel as if he “belonged to a family of nation builders.”

But if DNA beckoned him to public life, Ignatieff also acknowledges that he grew up in an environment — and around the likes of Lester Pearson and Jack Pickergill — where “good government…was [viewed as] the ultimate solution to any national problem.” It’s a perspective that may have shielded him from the new realities that awaited his return to Canada after his 30-year absence.

This admission lays the groundwork for the stunning self-doubt that winds its way through the greater part of his story. Here we begin to see the transformation of Michael Ignatieff. A man who was always the smartest guy in the room finds himself “about to spend the next five years of my life in a state of constant dependence on the opinions of others”; he “had to unlearn being clever, being rhetorical, being fluent.” This is how he describes it: “As you submit to the compromises demanded by public life, your public self begins to alter the person inside. Within a year of entering politics, I had the disoriented feeling of having been taken over by a doppelgänger, a strange new persona I could barely recognize.” His rude exposure to politics seems to draw him to a conclusion that to sublimate your authentic self and become someone else (being dependent on “the opinions of others” and “unlearn[ing] being clever”) is a prima facie prerequisite of the new craft he wished to ply.

And so he tries to adopt a new persona and begins to play the game by these rules. He gets on the Liberal Express bus and tours small-town Canada, kissing babies, slapping backs and demonstrating that he appreciates “how much depends on making a connection, any connection, with the people listening to you.”

We also know how this worked out.

In Ignatieff’s telling, his efforts to “connect” with average Canadians failed because his opponents “denied me standing in my own country,” robbing him of his authority to make his case. He is, of course, referring to the Conservative attack ads that accused him of “just visiting” and claimed that “he didn’t come back for you.” He admits that this relentless cant “did contain enough truth to be credible” — he had, after all, been out of the country for 30 years. He also notes that “the longer you leave an attack ad unanswered, the more damage it does,” attributing the effectiveness of the Tory ads to the Liberal Party’s lack of funds to counter with a campaign of its own, as well as the media’s lack of interest in the stump speeches of an opposition leader.

But by this point in the telling, you begin to see what everyone else saw but Michael Ignatieff could not. The Michael Ignatieff we saw trying to wage retail politics was not just unconvincing, but a candidate who smothered and denied the very virtues that originally made him such an appealing addition to public life. Take this passage: reflecting on the 2011 campaign, he claims that “the best part about being a politician is that you live the common life of your country: at the lobster festivals, county fairs, demolition derbies, corn roasts, rodeos, backyard barbecues and holy days at the synagogues, temples, mosques and churches…I served cotton candy, sampled samosas, threw out the first pitch, flipped burgers, fired the starter’s gun, rode horses in the parade and felt how good it is to be in places where no one can be turned away and where we share life together.” And “I loved every minute of it.”

Now I have no reason to doubt that Michael Ignatieff found a certain epiphany in the common sense and common occurrences of common folk. But by his own admission, he confessed that “none of this [the glad-handing and the small talk of campaigning] came naturally to me,” including physical contact with people. And I do not believe for a minute that he ever thought that this was “the best part about being a politician” or even that he “loved” it — or, more damningly, that this was “what he came back for.” While I am neither Sigmund Freud nor a clairvoyant, I suspect that the author is being more dishonest with himself than with us.

Here is how the real Michael Ignatieff seeks to explain his understanding of what the “common touch” of a politician and a connection with the voter require: “These are ancient arts, the skills that are commended in -Baldassare Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier written in the early sixteenth century…The word he used to describe the key talent in politics was “”˜sprezzatura.‘“ (In case you are bewildered by this curious definition of what it takes to be a man of the people, he offers the reader some assistance by noting that “this is without an exact equivalent in English.’“)

Watching Ignatieff throughout his time in politics, I was reminded of a great hockey goaltender who had been hit in the head once too often; every time an opponent drew back his stick to shoot again, he winced, rendering himself unable to stop the puck.

Michael Ignatieff didn’t come back to ride a horse in a parade, but when he did, not only did he look awkward and out of place, he also reduced himself to “just another politician” pandering for votes. Indeed, it was this inauthentic self that he put on display that robbed him of his standing and authority and gave credence to the claim that perhaps “he didn’t come back for you.”

Ignatieff came back because he was a superior intellect, with an evolved understanding of the world and Canada’s role in it, and — whether through hubris or ambition — believed he had the talent and wherewithal to run the country. Early after his return he wrote — without the counsel of his fart catchers — an 8,000-word policy manifesto entitled “An Agenda for Nation Building.” In it he laid out his prescription for righting wrongs against Canada’s Aboriginal peoples, improving productivity through investments in higher education and research and development, and restoring central Canada’s economic prowess by investing in high speed rail and knitting the country together with a new national energy grid.

Yet for the next five years, Canadians heard nary a word about these innovative and bold ideas. Had he stuck to that belief in ideas — and shown evidence of it instead of listening to the opinions of others or buying into the notion that he had to turn himself into someone he wasn’t — he might be prime minister today.

Reflecting on his shortcomings — and housed more comfortably, once again, in the hallowed halls of academe — Ignatieff finds solace in his vast understanding of the history of intellectual thought. He notes that brilliant men, from Cicero to Edmund Burke to de Tocqueville to John Stuart Mill and Max Weber, all tried their hand at the real world of politics. All were found wanting. “Why theoretical acumen is so frequently combined with political failure throws light on what is distinctive about a talent for politics,” Ignatieff writes. “The candour, rigour, willingness to follow a thought wherever it leads, the penetrating search for originality — all these are virtues in theoretical pursuits but active liabilities in politics, where discretion and dissimulation are essential for success.”

This is an excuse dressed up in the fancy cloth of Ignatieff’s usual good writing. Authenticity matters in politics. Ignatieff’s mistake was the failure of nerve to be himself. He lost playing by someone else’s rules, and yet now declares that these rules are immutable.

It’s a conclusion that leaves me wondering how someone so smart about so many things could be so wrong about the one thing he seemed to care so much about.

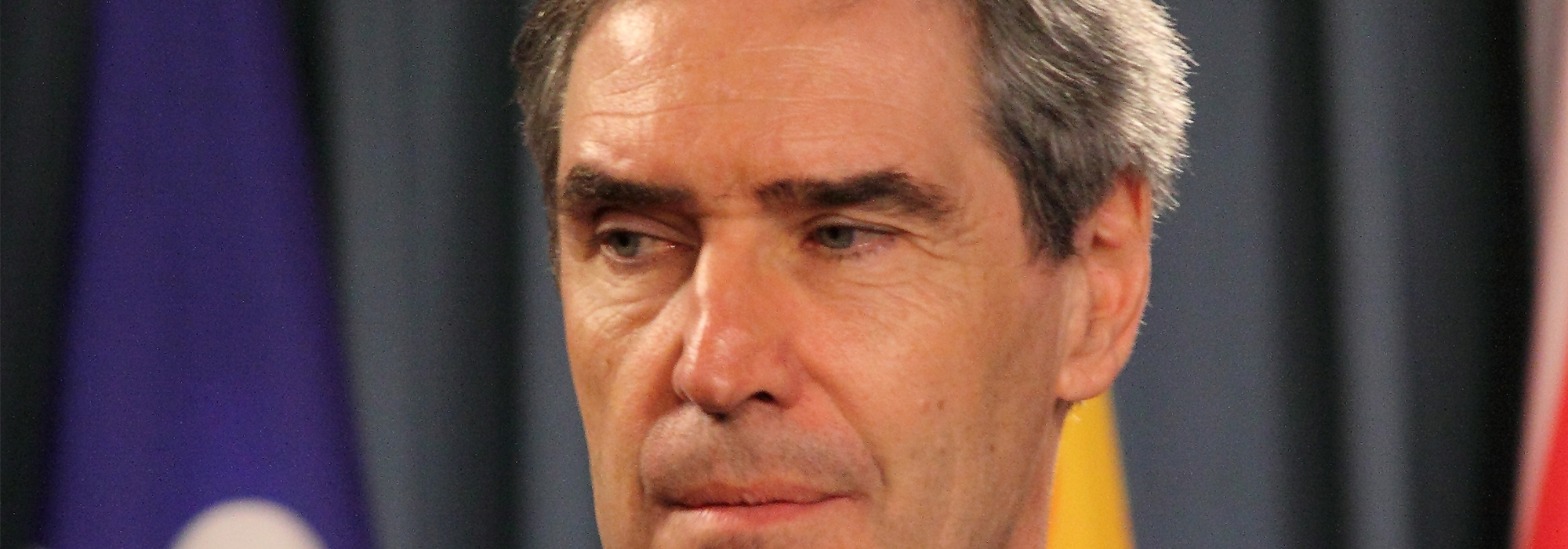

Photo: Art Babych / Shutterstock