On May 2, Canadian federal politics awoke from the plunged it nearly two decades ago. The bizarre 1993 election saw the destruction of Canada’s founding political party and an improbable new Quebec succubus attaching itself to the body politic. The campaigns that followed in the 1990s devastated the NDP. The division of English-Canadian Conservatives into bitterly feuding factions, followed by the theft of their Quebec base by the Bloc, meant that Canadian Liberals could fool themselves for more than a decade that they had returned to their glory days.

Jean Chrétien could bask in the same glow as Lester Pearson and Pierre Trudeau as leader of Canada’s natural governing party. Sadly for the Liberal Party, the damage done to its Quebec base by Trudeau was concealed by the party’s ability to sweep Ontario in this period. The decline in francophone support for the Liberals in Quebec is a constantly sloping line from 1980 through to 2011. That reality was masked only by the party’s rock-solid hold on Quebec’s anglophone and allophone voters. Now, even they are beginning to move.

The distortion of the Reform/Alliance split on the right, political deep freeze into which Quebec had with the ongoing grip of the Bloc Québécois on at least 50 MPs, meant that for Canadians who did not live in one of the 50 to 75 competitive ridings there was little point in paying attention to increasingly hysterical partisan rhetoric, let alone voting. No wonder the years after 1993 saw a secular decline in voter turnout, especially among the young.

Federal politics appeared to be as rigged a game as any in Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt, with genuine political contests here and in Cairo confined to internal power struggles for nomination and succession within the main parties. Until 2000, to be nominated as an Alberta Conservative or an Ontario Liberal was to be guaranteed a seat and a pension, no less certainly than in any Arab faux democracy.

Cracks in this unnatural frozen political landscape appeared in 2004 when the Liberals squandered their governing advantage after a decade of adolescent leadership battles. A wider fissure emerged in 2006 when Stephen Harper, having reunited all but the Quebec wing of Canadian conservatism, won a narrow victory. The foundation shook further when he solidified his opening in Quebec and Ontario in 2008, and thwarted an attempted parliamentary coup by his enemies that November.

The conventional wisdom over the past five years has been virtually unanimous: that the Bloc’s removal of such a huge slice of political real estate, combined with the solid hold of Liberals on much of urban Canada and the Tories’ advantages from Thunder Bay west, doomed Canadians to another in an apparently endless set of shaky minority Parliaments, following yet another unpopular and apparently pointless election.

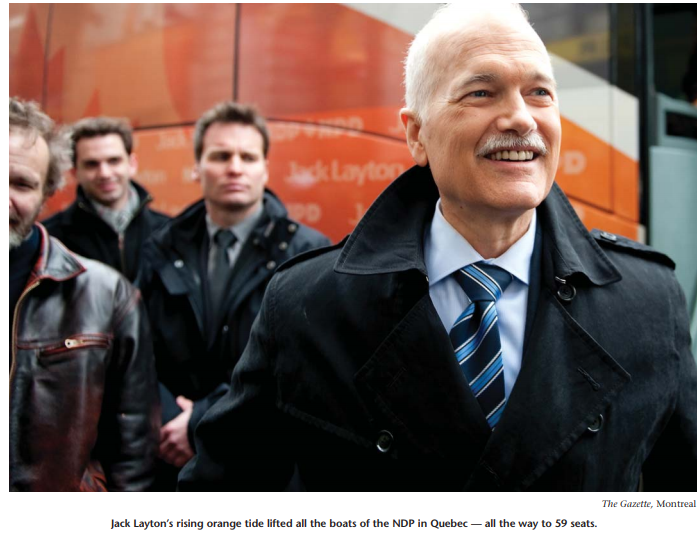

Once again, Canadian voters humiliated pollsters, pundits and political hacks by exploding the conventional wisdom in a totally unpredicted manner. Quebec voters woke Canadian politics from its torpor, seizing the opportunity to assert their view of the necessary direction of national politics. The first clues came in a stunning poll prior to Easter weekend, followed by an astonishing increase in Jack Layton’s personal popularity in the province and culminating in the hours before election day with almost rock-star-like events featuring “le bon Jack.”

Once again, Canadian voters humiliated pollsters, pundits and political hacks by exploding the conventional wisdom in a totally unpredicted manner. Quebec voters woke Canadian politics from its torpor, seizing the opportunity to assert their view of the necessary direction of national politics.

Polls played an inordinate role in this campaign once again. Pollsters love to insist they merely record trends and do not influence them. This is nonsense. When a campaign is hit out of the blue by a bad poll, morale sags, volunteers quit, donations dwindle and the campaign often makes gaffes in a desperate effort to regain momentum. It can be the start of a vicious spiral, with media reports mocking the failing campaign and the depressed turnout at events, each pushing the party or candidate down news agendas as the newly designated loser.

The crack cocaine of this decade in election polling — overnight tracking polls — has heightened the phenomenon. Political hacks up until the wee hours of the night before would stumble out of bed at 6:45 a.m. each and every morning this time, firing up their BlackBerrys and laptops, then sitting impatiently counting the minutes until Nik Nanos’ overnight numbers moved on the Internet at 7 a.m. Nik’s numbers shaped the thinking of the media outlets as they planned their campaign coverage and its tone. Morale and money shifted every time the numbers reversed direction, as they did several times over the month.

But it was a CROP poll out of Quebec that caused jaws to hit the floor across the nation, mid-campaign, late on Wednesday, April 13. It was this campaign’s hinge moment for the professionals. CROP and Leger are regarded as the gold-standard opinion trackers of the very fickle Quebec electorate. Their sample sizes are large, their analysts’ depths of experience impeccable. So when CROP reported a massive jump in NDP support in Quebec, placing it ahead of both the Conservatives and the Liberals, and reported a sharp drop in Bloc support, heads snapped throughout political Canada. It was a rogue poll, Liberal pundits initially spun; it was “not serious,” said some Quebec commentators, because the NDP could never translate it into seats.

The CROP poll was like a depth charge dropped from high above its submarine target. It tumbled through murky political waters, sending increasingly loud pings of imminent danger back to the nearby campaign motherships. It was embargoed for publication until the morning, but spread lightning-fast through the political Twitterverse. The explosion came with the morning news channel’s campaign reports. First, reporters and political hacks exchanged brief profane incredulous messages; next, campaign workers across the country spread the impact nationwide within minutes. New Democrat heads exploded, and the Liberal campaign balloon began its slow sagging drift in the subsequent poll numbers.

The poll’s timing could not have been worse for the Liberals and the Bloc, coming just as the impact of the debate was beginning to sink in and families were gathering for Easter and Passover holidays. Subsequent numbers did not immediately confirm the CROP data, but by the end of the second-last week of the campaign, two improbable developments appeared to be on the edge of unstoppability. The Bloc was in real trouble, though it was not yet certain to whose benefit. Secondly, the Harper campaign was holding steady in Ontario with some signs of growth at the expense of the Liberals.

Up to that mid-campaign polling eruption, Election 41 seemed to be fulfilling pundit expectations: Harper was wooden, controlled and controlling, travelling in a security bubble, banging on about the disaster that would destroy Canada if voters were not wise enough to give him a majority. The media and his opponents made great sport and caricatured his obsessive need to control everything from the liquor consumption on the campaign plane to the number of questions he would permit reporters to ask.

The exceedingly low expectations for Michael Ignatieff allowed him to surprise observers by giving rambling, high-energy, sweaty performances to enthusiastic crowds. But some of the more seasoned Liberal operatives muttered quietly that he had no message discipline and that his love of the first-person pronoun and of stories with himself at the centre made drawing on the Liberal brand, its achievements and its heroes — let alone a clear simple message about his vision of the future — virtually impossible.

Layton stumbled out of the gate, literally and figuratively. He hobbled onto his campaign plane only weeks after exceedingly painful hip surgery, into small, half-filled rooms, and seemed to lack his usual punch as a political performer. The early poll numbers were not helpful. The media’s lazy default preference of forcing a two-horse race as quickly as possible began to deliver the New Democrats’ nightmare — a squeeze off the front page and down the nightly newscast lineups.

As usual, the Bloc got little coverage in English Canada, except when it was clear that Gilles Duceppe was off his game, performing weakly in both the English- and French-language debates and campaigning lazily and poorly. Elizabeth May got a brief flurry of national attention for her exclusion from the national debates, but her strategy of getting herself elected in a distant Vancouver Island constituency meant that she basically wrote herself and her candidates out of the national campaign. Her significant victory in defeating Conservative cabinet minister Gary Lunn was a personal vindication of her decision. It remains to be seen whether she has sacrificed the Green Party on the altar of her ambition; the party lost nearly half its votes nationally.

The plot line for this election was set in the fall of last year, when it became clear that there was little prospect of the Liberals breaking out of the frustrating zone of support where month after month of polls had placed them — the mid to high 20s. The party knew that it had to force an election in the spring at the latest for several external reasons: the Ontario provincial election was set by fixed-date legislation for October 6, ruling out any federal election later than June. The newly elected BC Liberal premier, Christy Clark, had also signalled that she intended to advance that province’s election to the late fall. So there was little prospect of another clear window until the spring of 2012.

Waiting another year presented an additional raft of problems for Ignatieff. Supporting the government and its likely austerity budget and its increasingly draconian crime bills for another year — to the sneers and derision of the NDP — was untenable. Quebec was due for an election in 2012 or early 2013, to be preceded by a leadership race to choose Jean Charest’s successor, not the ideal circumstance for staging a federal Liberal comeback in the province. In addition, the Canadian economy seemed on the mend; in another year, recovery might be a demonstrable political success for the Harper government.

Sadly for the Liberals, their lack of internal discipline meant these strategic calculations leaked and became part of journalists’ stories for months throughout the fall and the winter. The Conservatives adroitly used the increasingly obvious Liberal hunger for a campaign to do two things: delay the date of their own budget until late March, granting a much longer window for the economy to benefit from the injection of stimulus billions.

But it also allowed the Tories to do something much more damaging to the Liberals — to spend millions on demeaning, but highly effective, television attack ads. As one foolishly candid young Tory war room staffer admitted to Paul Wells of Maclean’s, the party’s goal in this second demolition of a Liberal leader was strategically quite different from the first.

The entire Conservative campaign message was clear to anyone paying attention a year before the writ was dropped: “We need a majority to protect the Canadian economy and your family from the disaster that would result from a separatist/socialist coalition.” It was a bold and high-risk campaign message.

Stéphane Dion was destroyed by a campaign undermining his competence to lead and his alleged inability to take tough decisions, summed up as: “Not a leader!” The even more brutal devastation of Michael Ignatieff was one step lower in political ethics. As the young staffer gloated, the Tory goal was to frame Ignatieff as “malicious” concerning the personal interests of Canadians and as a self-seeking “opportunist” with no legitimate credentials as a leader.

Liberals were furious at the effective use of yellow journalism to promote false allegations against their leader, along with attack ads designed to convey an impression of Michael Ignatieff as an unpatriotic Canadian and a chameleon-like congenital liar. They should be grateful that only their sagging poll numbers, and some pushback in the Tories’ own research about Canadians’ reaction to the severity of their carpet bombing of Ignatieff’s life story, halted the publication of even more scurrilous campaign material designed to convey his failure as a husband and father and to portray him as a “cosmopolitan” who frequently sneered at Canada from his perch as an effete Europhile intellectual.

Layton had an entirely different experience in the final days of the campaign as a result of a similar Liberal war room stunt, using the hapless Sun TV gang as the facilitators. A 15-yearold story was fed to the new news channel. It claimed that Layton had been a found-in at a massage parlour when he was a Toronto city councillor. The New Democrat war room pounced on the story, issuing counter-attacks within minutes from his wife, his lawyer and Layton himself. Still, having the leader’s name and massage parlour in the same headline, even if in a story carried by a station whose viewers were mostly employees and their anxious family members, could not be a good thing, thought most veteran campaign watchers, including this one. We were wrong. Layton enjoyed what one cheeky pollster privately called “a bathhouse bump.”

The Conservatives’ frame for this election was revealed two years earlier, when Harper, in a series of interviews, took his coalition-bashing message out for a trial run. Most pundits — and his opponents — shook their heads at his obsession with the battle of November 2008, one that he had after all won. We should all have paid more attention. By 2010, Jim Flaherty was regularly framing the second half of the message: “We saved Canada during the great recession. But our economy is still fragile. We can’t risk changing horses now.”

The entire Conservative campaign message was clear to anyone paying attention a year before the writ was dropped: “We need a majority to protect the Canadian economy and your family from the disaster that would result from a separatist/socialist coalition.” It was a bold and high-risk campaign message. For a personally unpopular prime minister, about whom many Canadians still had deep anxieties about secret right-wing political desires, and who had been refused a majority twice previously, to rest his entire campaign on such an appeal seemed bizarre. He was right and the conventional wisdom was wrong.

Beyond knowing they were going to run another demonization campaign against the Prime Minister, the Liberals struggled about what to put in the shop window right up to the moment of their decision to defeat the government. Their general thesis was that their cheesily named “Family Pack” of small social welfare goodies would be the centre of their offer, with their counter to the Harper appeal for a stable majority being that the Harper government was fundamentally undemocratic and politically corrupt.

That this ethics attack was driven by the leader’s own conviction, rather than research, was revealed in a bizarre comment he made to a private meeting of Liberals. He claimed that Harper was “opposed to elections” because that was when he lost his power “to the people.” One may make a long list of criticisms of Harper’s understanding of how parliamentary democracies should operate, but fear of elections is not among them — he triggered two, and he threatened the former governor general with a third if she did not grant him a prorogation. Canadians simply did not believe that Stephen Harper was a secret northern Hugo Chavez demagogue waiting to be outed.

As Ensight Canada’s post-election research first revealed, voters were fed up with hyper-partisan rhetoric and simply did not believe, as lawyers would put it, that the Liberal Party approached this issue of political corruption “with clean hands.” An arrogant, angry messenger delivering an improbable attack message, while crowding out his own positive vision, was the core of the Liberals’ strategic folly.

The New Democrats’ ballot question was the last to be agreed internally, and was the most subtle — almost too subtle to be noticed, it appeared for the first few weeks of the campaign. An NDP leader’s strategic campaign dilemma is brutal and perennial. At 18 to 20 percent in the polls, the media and the voters know you are not going to be prime minister and begin to write you out of the story. So for New Democrat strategists, the challenge is to develop a campaign meme that sidesteps that dead end. David Lewis did it brilliantly with “corporate welfare bums.” You could vote for him to fight corporate welfare whether he was prime minister or not. Another classic, in various forms, is “We’ll fight for you and your family” This is less effective in a tight strategic voting race, though, where soft New Democrats might drift to the Liberals to block a Tory majority.

Jack Layton wanted a spring 2011 election as keenly as the Liberals did. Observers who doubted his conviction, given his flat poll numbers and ongoing health irritations, did not understand what a sophisticated long-term political strategist Layton had evolved into. He wanted, as did Harper, to face Ignatieff. It was not clear that the embattled Liberal leader would survive another year with the party stalled in the mid-20s. Layton also wanted to face Gilles Duceppe, whose weakness he had sussed, and whose ability to launch a revival of the Bloc under a new leader might get in the way of the NDP’s Quebec ambitions. Most of all, he could see also that another year of Conservative governing success, punctuated perhaps by a provincial Conservative victory in Ontario, would not be helpful to NDP fortunes.

Layton was a seasoned and confident campaigner, and he thought he had the measure of his opponents after their three previous rounds. In a private conversation, late last year, he fretted that Duceppe and Harper would do a deal on the budget to prevent an election one more time. He was almost right. The Conservatives did try to do a deal on the harmonized sales tax with the provincial government, but the PQ, not eager to have the Charest government win such a victory, instructed its federal cousins to raise the ante to impossible levels. Duceppe did as required, saying he needed another $5 billion in Quebec goodies to support the budget. The Tories snorted and gave up on Duceppe, knowing there would be no possible deal in that direction. Ironically, they quietly announced at mid-campaign that they would complete an HST deal with Quebec by September.

Conservatives were outmanoeuvred by Layton in the pre-budget dance. Layton presented a face of sweet reasonableness in demanding a relatively modest set of health care, pension and homeowner subsidies and reforms, and declared his willingness to negotiate. The government met him halfway, it thought, in a series of discussions convened by the Prime Minister. Layton kept his opponents and the media guessing right up to budget day, when to the surprise of many he pulled the plug dramatically, triggering the election. Curiously, the Liberals thought that their effort in the days that followed, to be seen as the official executioner over ethics, was of political benefit to them. It wasn’t.

It might have been possible for the Harper government to deliver everything that Layton would need to support its budget, but with considerable savvy Layton set his bar just tantalizingly out of reach, by adding demands on pensions that would require provincial assent. His bias was strongly in favour of defeating the Harper government, but as he told his caucus and campaign team, it was essential that they bargain in good faith, as a contrast to both Duceppe’s foolish goalpost moving and Ignatieff’s simple obduracy.

The New Democrats’ strategic framework had been set weeks earlier, following the first discussion between Harper and Ignatieff. Unlike the other party leaders, Layton had developed a practice of leading hours-long late-night conference calls with a group of a dozen to two dozen key advisers and allies across Canada. The debate that night was about how to respond to the government’s offer. It was even longer than usual. Slowly and subtly Layton moved the consensus to a budget defeat and an election unless his demands were met. Later he performed the same careful consultation and persuasion with his caucus, several of whose senior Ontario and BC MPs had been very skittish about his strategy.

Well after midnight that same night in a Toronto consulting firm’s boardroom, a small group of Layton team members turned the range of options over and over, their strategic reflections well lubricated by a case of Canadian wine. Their conclusion was that an election was the goal, with avoiding been seen to have triggered it, until as late as possible, the essential tactic. To their delight the Liberals volunteered for the role of Harper slayer and chose to make the trigger ethics, not economic fairness.

However, only days before the government’s fall, the NDP was still struggling with the best crystallization of its ballot question. Many close to the leader and caucus wanted it to be “fairness for you and your family,” with the usual shopping list of social policy goodies that often framed an NDP campaign. The problem with this approach was that the Liberal Party’s leftward tilt — the most astonishing part of which was abandoning the very corporate tax cuts it had launched in government and then supported the Harper government’s implementation of — made it likely the Liberals would try match NDP promises here, too.

NDP national director Brad Lavigne and chief of staff Anne McGrath, the two staffers closest to Layton, knew that their challenge was to offer persuadable voters clear proof that Layton was the strongest “antiHarper” choice, in the face of a Liberal strategic voting onslaught. They resisted the pressure from some veterans to deliver a big-picture vision and ran a nearly picture-perfect campaign. They also tacked carefully between bashing first Harper and then Ignatieff, careful to frame the criticism in terms that would allow uneasy partisans of either opposing party to still come to them later. They needed to convey the message “You have a choice” believably, in the face of often cruel poll numbers.

Brian Topp had the epiphany for the apparently vacuous slogan that Layton used with increasing impact as the campaign unfolded: “Ottawa is broken!” By starting with a “running against Ottawa” message, Layton won permission from angry voters to go on to offer a solution, one that he alone would deliver, on pensions, health are, home heating oil, etc. Topp lays out the path that led to this subtle positioning in his article elsewhere in this issue.

In the final week, Layton’s surge prompted changes in all three campaigns. The Bloc and the Liberals attacked the NDP with a series of hilariously bad attack ads, the most hilarious being a Liberal claim that Layton and Harper were “two sides of the same coin.” Harper attacked the prospect of a Layton-led coalition, flipping Ignatieff into the junior role. This helped spook some Liberals into voting Conservative, especially in suburban Toronto. Ironically, it helped other Liberals decide to vote for the NDP as likely winners. In the GTA ridings in and around Toronto, the combined impact was a blue army from the north and an orange army from the south, crushing the Liberal fortress of Toronto in a pincer movement.

But the big question mark going into the close of polls on election day was whether the NDP’s astonishing growth in Quebec was going to deliver victories to candidates who had never set foot in their ridings, where the campaign organization was a phone number in another town. There were many red-faced pundits and pollsters on election night. Not among them was Allan Gregg, who not only predicted the Liberal nightmare in Toronto, but also foresaw what was about to happen in Quebec. As he said privately five days before election day: “When you are at 51 percent of francophone (!) support in Quebec — that’s nearly as high as Trudeau in 1980 — no one has a safe seat anywhere in the province.”

Even so, seasoned political hacks, pundits and opposing politicians had a collective heart attack as the first poll results from the unique riding of Gaspésie-Îles-de-la-Madeleine emerged at about 9:15 EDT on election night. The riding carves an arc along the southern shore of the mouth of the St. Lawrence River and the tip of the Gaspé Peninsula and also includes the romantic Îles-de-la-Madeleine in the middle of Canada’s primal river.

Gaspésie-Îles-de-la-Madeleine, by a quirk of geography and history, votes in the Atlantic time zone, unlike the rest of Quebec. So its first results came minutes after Newfoundland’s puzzling outcome, followed by Nova Scotia’s equally mixed data, began to leak. As I paced in a Toronto TV studio, my reaction was echoed across the country in campaign offices, in the hotel suite where Harper sat with his family and advisers in Calgary, and probably most painfully in many Bloc Québécois campaign offices and victory headquarters across the province.

The improbably named Philip Toone — an NDP candidate so modest in his ambition that he admitted, blushingly, that he had not been able to afford the cost of the ferry ride to the islands to visit his voters on the Îles de la Madeleine — stole an astonishing 30 percent of the vote in the first poll reported, which climbed quickly to a clear majority of more than 50 percent within minutes.

“Holy shit!” I whispered to myself, before remembering I was wearing a live microphone. It was true: Quebec voters were going to blow up this election. It was the first real proof of what the polls had been reporting for weeks. Quebec voters did not give a damn whether their NDP candidate was in Las Vegas or had yet started to shave. Desperate for change, they came out in the tens of thousands to vote for “Smilin’ Jack’s” local representative. It was the first proof that May 2 would mark the end of an era in Canadian politics, and a massive shift in the Canadian electorate.

The humbling of the Liberal Party, the public revelation of a rot that had begun three decades earlier, one masked by the Bloc and a divided family on the Canadian right since 1993, was by dawn painfully visible from Vancouver to Halifax. The destruction of the temporary response to the failure of the Meech Lake Accord, the Bloc Québécois, was even more absolute — four aging MPs, not including Gilles Duceppe, were all that remained of a party that had twice held 54 seats.

Harper’s political war machine had been able to convert its 39.6 percent of the votes, and an increase of fewer than 600,000 out of 14.7 million votes cast, into 166 — or 54.2 percent — of the seats. In a 21st-century version of trench warfare, it had moved its battalions a few miles forward into suburban Toronto, taking more than 400,000 new votes and winning four secure years of majority government. Harper had achieved something no one had ever done, a national majority based west of Quebec. The capture of Ontario, along with his western bastion, gives him a political freedom of movement no Canadian prime minister has enjoyed since Mackenzie King.

But it was the astonishing break-through of Layton’s New Democrats in Quebec and his solidifying of beachheads in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Alberta and BC, that was at least as electrifying a result of this very Canadian election. The party made big vote gains in six provinces. A combination of vote splitting by Liberals in Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan and the late surge of Blue Grits to the Conservatives cheated the party out of recapturing seats in traditional strongholds like Winnipeg North, Saskatoon-Rosetown-Biggar and Vancouver Island North.

The humbling of the Liberal Party, the public revelation of a rot that had begun three decades earlier, one masked by the Bloc and a divided family on the Canadian right since 1993, was by dawn painfully visible from Vancouver to Halifax. The destruction of the temporary response to the failure of the Meech Lake Accord, the Bloc Québécois, was even more absolute — four aging MPs, not including Gilles Duceppe, were all that remained of a party that had twice held 54 seats.

A mid the euphoria of election night at the Layton victory party, some party veterans muttered that that was just as well. If the NDP had won another dozen seats in BC, the Prairies and Ontario, the country would be faced with another minority parliament. Harper’s endless warnings that it would have triggered an instant power struggle with a coalition as the likely outcome were not a paranoid fantasy.

Serious discussions at a very senior level about roles and agendas and timing had indeed taken place. A very secret “scenarios committee,” composed of statesmen and officials from several political tribes, had been convened months earlier. They had prepared a plan for government, a draft Throne Speech and budget, and had tested its main themes with senior Liberals and New Democrats. Harper’s sabre-rattling about a coalition was not wrong, except that everyone involved in this year’s discussion was adamant about one change: there was no role, formal or informal, for the Bloc. The plotters had learned the lesson of the infamous “Three Stooges” photo of 2008, used so effectively by the Harper government to demolish support for that effort.

Constructing such a coalition would have been constitutional, perhaps even an appropriate political solution to a hung Parliament. But it would have severely strained NDP/Liberal relations, if the Grits had hung onto opposition, especially given the contempt many Liberals and most New Democrats felt for the hapless Liberal leader. The project would have been launched over screams of rage from the Conservative establishment and its phalanx of media allies. In the cold light of the morning after, most veterans of both the orange and red teams breathed a sigh of relief.

Absorbing their gains would be a tough enough challenge for the New Democrats’ political and managerial leadership, without the additional strain of juggling the stresses of a coalition government with a deeply embittered Liberal caucus. For Liberals, leaderless, deprived of many caucus veterans and heartbroken at the appalling election result, mustering a professional negotiating team for detailed coalition bargaining would have proved challenging. Moving from the bitterness of defeat to the exquisitely delicate and dangerous process of coalition building and execution might have ended in tears and recrimination.

In the aftermath of their historic thumping — reduced to third place for the first time in their history — Liberals promptly began fighting over the slim spoils of defeat. They couldn’t even agree on the choice of an interim leader, much less a timeline for electing a permanent successor For the generation of Liberals schooled in the tough discipline of the Pearson and Trudeau eras — where one did not speak ill of a fellow Liberal on pain of public rebuke — it was a searing postelection humiliation. For the generation that sharpened its teeth in the bloodshed of the Chrétien-Martin wars, it was Liberal politics as usual. For many young Canadians it was proof of the vulgar and venal nature of partisan politics. The Liberals’ fratricidal squabbles are more valuable to Harper and Layton than anything they could do on their own. Each wisely guarded his counsel, while no doubt hooting with sardonic glee in private at the demise of institutional discipline in the most successful Canadian political party of the past century.

By 9:30 p.m. on election night, returning to their traditional role in Canadian politics, Quebecers led the country to its new leader of the opposition and to our new prime minister. For the first time in nearly two decades, Quebecers pointed Canadians to their native son as their choice to lead them. That he is an anglophone who has spent most of his life in Toronto blinded many non-Quebecers to the power of his heritage and his deep connection with his native province. They failed to push Jack Layton beyond number two, but they signalled as clearly as their parents had, in 1958, 1962, 1968, 1984, 1993 and 2006, that Quebecers had decided to return to their famous vote efficace — a late-blooming tidal surge in one direction.

As one of the sages of federal journalism on the role of Quebec in Canada observed in a private message on election eve, Quebec’s Ottawa representatives have for decades changed federal politics. He went back to the Noranda used-car dealer Réal Caouette’s Créditiste victory in 1962, which frightened federal Liberals into the Bilingualism and Biculturalism Commission, the august review of a path forward from les deux solitudes of Canada in the 1960s that laid the foundation for work that continued in a new century. Then came Trudeau and the “three wise men,” who laid the next level of brickwork in modern Canada, building the promise of a bilingual federal government and the Charter of Rights, which, with medicare, frames much of what is uniquely Canadian for two generations. Mulroney’s massive 1984 sweep brought another generation of determined Quebec politicians to Ottawa.

The Quebec Mulroneyites provided the necessary solid foundation for the free trade battle, and they shed gallons of political blood attempting to repair the rent that Trudeau’s constitutional crusade — absent Quebec — left in the fabric of the country. Mulroney was betrayed by key Quebec Liberals and then by his own chosen lieutenant in the mission. The veteran Quebec watcher mused about what changes to federal politics this new generation of ambitious young politicians would deliver.

Among the poisoned legacies of 1993 was the eruption of the Bloc Québécois, planted and nurtured by the provincial souverainiste movement, as its agents of influence in Ottawa. For two decades it froze Quebec out of federal politics and locked Canada into a bizarre calculus where 50 slices were always removed from a 300-slice electoral pie. It was as if the president of the United States were elected by all the states except New York and California.

The constitutional battles that had given it life — from the Victoria Accord of 1970 through endless conferences and container loads of documents and culminating in the Constitution Act of 1982 — were launched before any Quebecer under 40 years of age was born. The Bloc had lasted long past its sell-by date for two reasons: a savvy and determined leader in Gilles Duceppe, and the good fortune of the sponsorship scandal, followed by Stephen Harper’s foolish attack on Quebec arts and culture. The Bloc was absurd and the damage it inflicted on Quebec in Canadian political life was finally undone only this year.

For Jack Layton, that Election 2011 should have turned out thus was the sweetest part of an exceedingly sweet night. Refusing to be discouraged by Ed Broadbent’s heartbreaking experience in his efforts to build a federalist social democratic beachhead in the face of heavy souverainiste machine-gun fire, or by the desolation of the 1990s for Néo-Démocrates, Layton began the task of rebuilding from the moment he arrived in the leader’s office in 2003. In the office of the new leader of the official opposition, Quebec management will fall under a team led by Raymond Guardia, recruited in the Broadbent era, who in turn recruited many of this year’s improbable young Quebec victors. He and Jack Layton — not, as some pundits have speculated, Tom Mulcair — will now teach them politics.

Layton learned one of the most important lessons in politics, and often in life: it is the lessons of the most stinging defeats that pave the path for future victory. Using some of the same organizers and many of the same messages, Layton quietly built a new foundation for his party in the one province that had failed to embrace the CCF and NDP since the party’s founding in 1933. But he did not repeat an error of that earlier time, of making partnership with some in the souverainiste movement or Quebec labour who turned out to be Broadbent’s fair-weather friends.

For nearly the nation’s entire history from Macdonald to Laurier to King, Canada had been governed by politicians able to find the right partnership between Quebec voters and those in the rest of Canada. Often it was the product of an enduring partnership between an anglophone leader and a Quebec lieutenant, or, in the case of Laurier, St-Laurent, Trudeau, Mulroney and Chrétien, a Quebec native son able to build an enduring political bridge between two of Canada’s founding peoples.

Late surges of support for their chosen leader by Quebec voters presaged enormous victories across the country. Even in 2006, it was the Harper breakthrough in the Quebec City region, modest in seat numbers by historical comparison but dramatic in the conferred legitimacy it settled on an unknown leader from the opposite end of the country and of the political spectrum from Quebec, that allowed him to become an acceptable prime minister.

Election 41 was both a hello and a goodbye to Canadians for Liberal Leader Michael Ignatieff. Instead of taking an unpopular leader with a strong brand, a great front bench team and a large base of voters in virtually every province except Alberta and focusing on their strengths — everything but the leader — party strategists did the opposite: buried the brand, hid the key lieutenants, failed to mobilize the base with a visionary message and framed the campaign around the leader. That this decision failed is less surprising than that Liberal organizers attempted such a bizarre campaign. By week three, senior Liberals were muttering treasonously, a curious echo of the disastrous 1988 Turner campaign when the same circumstances caused some Liberal insiders to plot an unheard-of mid-campaign coup d’état.

For Jack Layton, who faced a shaky opening 10 days — his health being added to the usual desire of lazy editors to force a two-horse race as quickly as possible — this boneheaded strategic decision by the Liberals opened an inviting window. In another echo of 1988, Layton is far more popular with voters than is the NDP. In some polls he was the choice of five times more Canadians than Ignatieff, when asked whom they would like to spend an evening with. He parlayed that personal appeal into a new credibility as the anti-Harper choice.

Ignatieff had made it clear to intimates that he was not going to serve another term as opposition leader. His determination to move up or out leaked a year earlier when conversations he had about a return to academic life were revealed by the respected Toronto Star journalist Jim Travers. Travers, who died tragically only weeks before the election, was roundly denounced by Ignatieff and even by some of his own colleagues for the story. But he was not wrong; such discussions had indeed taken place — he only got the desired post wrong.

Travers had reported that Ignatieff wanted to replace Janice Stein as head of the prestigious Munk Centre. As one academic friend of Ignatieff’s said acidly when the story appeared, “That’s nuts! That job is non-stop hard work. He’d never want a gig like that.” He was right; the post Ignatieff had trailed his coat about was similar to what he was offered a year later, a loose “intellectual in residence” assignment.

An ungraciously brief period of mourning followed his defeat before he announced his next gig. Within days, friends at the University of Toronto secured his return to a university that had previously hired him — though his political career had preempted his earlier assignment. This time he was granted an elegant office and living quarters in the university’s most desirable college, cross-appointments to several of the university’s most prestigious schools and a “light” teaching schedule. The groans of protest among the university’s less favoured academics were exceeded only by those of the members of Ignatieff’s own political staff, who were all fired en masse the next day. “I guess they were right,” one bitter young staffer quipped. “He didn’t come back for us…”

Ignatieff’s tone-deaf approach to politics continued to the end. He gave an improbably long concession speech on election night, the longest most observers could remember, consisting mainly of stories about himself and road stories about the campaign experience of himself and his wife, Zsuzsanna Zsohar…and even then he failed to resign!

Wiser heads made it clear to him, overnight, that staying was not an option; he resigned with a blessedly brief speech the following morning. At the last caucus reception, held in Ottawa the following week, Ignatieff mingled briefly, staying only long enough for what diplomats call a “presence,” and then left the hundreds of grieving MPs and staff to drink through their sorrow alone.

It was not even a bittersweet ending for Michael Ignatieff, merely bitter. It should have been obvious from the first phone call that he was a fool to allow himself to be seduced, by two Toronto lawyers and one parttime documentary filmmaker, away from a successful career as a public intellectual into the far more brutal world of leadership politics. To someone more self-aware, more experienced at living — not merely observing the lives of ordinary people — it probably would have been.

He should never have allowed Alf Apps, Dan Brock and the great rainmaker Senator Keith Davey’s only son, Ian — who had never managed a campaign in his life — to be his sole reference group about such a fateful choice. A man less credulous about the painfully acquired craft, the often cruel but essential dues of a successful political life, would have been more cautious.

Several friends outside the Liberal Party and his lifelong, well-scarred political friend Bob Rae warned Ignatieff in the summer of 2005 that he was in no way prepared to make the leap from professor, author and TV host to the pinnacle of Canadian politics. But the Liberal Party was again desperate for a saviour and Michael Ignatieff was hungry for a Canadian legacy. Their mutual blindness sowed the seeds of disaster for the party less than six years later.

Jean Chrétien could bask in the same glow as Lester Pearson and Pierre Trudeau as leader of Canada’s natural governing party. Sadly for the Liberal Party, the damage done to its Quebec base by Trudeau was concealed by the party’s ability to sweep Ontario in this period. The decline in francophone support for the Liberals in Quebec is a constantly sloping line from 1980 through to 2011.

Great political leaders are born with, or learn by trial and error, the skill of communicating conviction, compassion and commitment. Intellectuals, as Christopher Caldwell in the Financial Times observed, are trained to develop precisely the opposite skills: distance, neutrality and flexibility. One’s partisans will grant a “yellow tailed dog,” in Joey Smallwood’s immortal phrase, the ingredients of greatness they seek in a leader — until they are forced to drop their suspension of disbelief.

But the more than 50 percent of Canadian voters who have little or no partisan DNA judge character first. They seek authenticity, sincerity in an untested leader, before even competence or demonstrated ability. This can come in several packages — “good ol’ boy,” “wise and cheerful uncle,” “helluva guy” — but the ability to connect emotionally through a camera lens and in person is essential. Bellowing like Phil Donahue, as one angry Liberal strategist put it, telling your audience to “rise up!” without making a case for civil disobedience, was not only unwise, it was insulting. As another Liberal friend put it, “The unspoken close to that sentence for me was ‘Rise up…you brainwashed, ungrateful, spoiled Canadians!’“

The election that ended with such a bang had been launched with more of a whimper from Ignatieff. Every campaign’s first week is a bit of a phony war, as all the teams work out the bugs in their campaign machinery, as the leaders work on refining their lines and as the media trot out their rehearsed conventional wisdoms.

Harper spent the first half frothing about the risks of a coalition, and the second half wishing that he had never offered to do a one-on-one debate with Ignatieff. The Liberal leader flubbed his response to Harper’s coalition attack for three days, then spent the closing days of his first week sneering at Harper’s “cowardice” in refusing to meet him “anywhere, anytime.” Ignatieff did not quite start clucking and flapping his arms at the mention of the Prime Minister, though some reporters came close. Jack Layton faced the inevitable harassment of every NDP leader over half a century: “Are you irrelevant? Why aren’t your crowds as big as his? Why are you doing so many/not enough events?”

The lazy editorial themes laid out by the punditi in advance of the writ played out desultorily in the first eight days: Harper was a grumpy control monster, Ignatieff was not the idiot we had reported him to be, and Jack Layton was old and sick and needed to lean on a cane. Voters, readers and viewers could be excused for turning to Wheel of Fortune or royal wedding speculation in preference to most of the vacuous political reporting of the campaign’s early days.

Ignatieff led the opening of week two with a clever combination of technology, staged openness and smooth presentation with the launch of the Liberal platform. That its content consisted of barely refreshed ancient promises, carefully blended with stolen NDP and even a few Tory proposals, was not important. Ignatieff, comfortably reciting its rhetoric while in conversation with dozens of Canadians electronically connected in a virtual town hall, was the message as well as the medium. Curiously, the Conservatives provided a hilarious contrast in their competing event that morning: the Prime Minister looking like the “before” scenes — the fat old guy shilling club memberships in a cheesy fitness commercial — offering tax credits for gym lessons!

The debate over debates dominated the early days in this campaign as it did in 2008. Elizabeth May’s bellowed rage at the broadcasters’ decision to exclude her once again provoked a storm of criticism of “the boys” at the head of each party and the networks. In contrast to Dion’s and Layton’s collapse in the face of similar criticism the first time, the leaders muttered their willingness to have her in the debate, but blamed her exclusion on the networks The controversy about the murky “broadcasters’ consortium” did have one positive outcome. It now seems likely that there will be a serious effort to establish an independent debates commission, as the Americans did a generation ago.

The two debates themselves had the same delayed time-bomb impact on the campaign as have several in recent campaigns. No victor was declared on debate night. Some commentators did pick up the damage that Layton inflicted on Ignatieff with his delicious knife blow over his Commons attendance record. His coup de graÌ‚ce: “You know, most Canadians, if they don’t show up for work, they don’t get a promotion. You missed 70 percent of the votes.”

Layton claimed that Ignatieff had the worst attendance record of any leader in Parliament — though exag-gerating his absence somewhat, it was later discovered.

Ignatieff looked as if he had just been jabbed with a stiletto to the kidneys, and stutteringly tried to change the subject. A more seasoned debater, a more skilful politician would have lashed back with the obvious rejoinder, one that one could almost hear Liberal strategists bellowing at their TV screens across the nation: “Well, Mr. Layton, I was out talking to Canadians while you were playing games in the House of Commons. You should try it.”

Harper’s robotic television performance — locked, like his stance in Question Period, on the camera, not his opponents — seemed to appeal to his base, though he looked more like a Ken doll burbling recorded lines triggered by a staffer pulling invisible strings than a real debater. But by the end of the following week, it was clear that Harper and Layton had each made inroads with their target audiences in the debates. Duceppe and Ignatieff were badly wounded. Layton’s French-language debate erformance was seen by some observers as the beginning of the rise of “le bon Jack” in Quebec.

A couple of decades ago parties historically weak in a riding or region would cheerfully send a young volunteer from hundreds of miles away into local bars and legion halls to get his candidacy papers endorsed by local voters, for a campaign in which he would never play a subsequent role. They were often prospective politicians about whose personal history of recreational drug use or views on alien abduction absolutely nothing was ever asked or known.

The outcome of this rather casual approach to nomination papers, common to each party’s “poteau” candidates, proved rather ironic for the NDP this time. A large number of its fence posts are representing huge numbers of Quebec voters as MPs in the House of Commons. Some appear to have been less than diligent in ensuring their supporters did not indulge in the time-honoured tradition of signing up the local cemetery as nominators.

This election was one of firsts and lasts. First majority for a prime minister fourth time out, first Green MP, first NDP official opposition, first opposition leader defeated in his own riding to think he had a future as leader. But it also marked the end of rituals from another era. Twitter made an ass of the Elections Canada ban on early release of election statistics from Atlantic Canada, despite stern warnings from that increasingly dictatorial regulator. It will surely be the last time it is so boneheaded — this inter-tubes thing is going to last, folks, really.

More dangerously, Lobbying Commissioner Karen Shepherd intervened unwisely into the political process by banning every political activist from supporting any candidate barring those certain to lose. Her effort to ban lobbyists from volunteering their expertise to political parties will doubtless lead to a court battle, as government relations consultant Walter Robinson deliberately set himself up for political martyrdom by refusing to abide by her edict.

This was the last election with the existing riding boundaries, as well. A delayed shake-up to implement new boundaries informed by the most recent census is now inevitable. The existing rules impose a crazy quilt: some provinces get a guaranteed minimum of ridings; rural voters can be weighted more heavily than urban; beyond a certain size geography is allowed to trump demography. Our system is not as gerrymandered as in days of old, but its anomalies do need to be addressed. One of the innovations of the last map-makers was to combine rural and urban voters such that numerical equivalency could be better maintained. Unfortunately, this formula has created hybrids that discriminate against rural and small-town voters. When the farmers of northwest Saskatchewan are lumped together with the city of Saskatoon, or the small towns of southern Manitoba are twinned in a forced marriage with suburban Winnipeggers, it is not the city folk who lose. Politicians, after all, go where the votes are.

We give PEI four seats by constitutional guarantee, though its voters in total are fewer than some big city or suburban ridings. We should acknowledge similarly that northern and rural voters cannot be forced into the same numeric formulas as urban voters, and lumping them as rural cousins attached to urban ridings is nonsense. To require that each riding not deviate more than 20 percent from a mean of 100,000 to 125,000 voters will remove MPs across northern and rural Canada and force their voters into ridings the size of large European nations. We support hospitals, schools and social services for remote communities far in excess of their per capita entitlement. Why would we not extend the same principle to their ability to participate in politics? If we have to expand the House another dozen seats, beyond the 30 already promised, to ensure that Atlantic, Prairie and Quebec voters, along with rural and northern Canadian voters, get fair representation, let’s do it.

This was the last election under current campaign finance rules. Harper promises to end the per-vote subsidy to national parties. This will undermine the weakest parties first — the Bloc, Greens and Liberals. New Democrats will be forced to rev up their retail fundraising efforts. Given their ability to demonize the Harper government to a progressive base, using all the tools of social media and direct marketing, this is probably not an impossible task. Harper might be wise to consider raising the contribution limits again. It is much harder for a majority government, forced to rattle contributors to give more, when an election is certain to be four years away. History would predict that the Conservative base would get smaller and sleepier in the comfort of the majority years.

Then there is the question of non-writ campaign spending. Until recently, no party had the money, and no broadcaster would accept it for political advertising outside an election. The Conservatives spent more than $50 million in the period between the 2008 and 2011 campaigns, much of it on research and advertising to demolish Ignatieff’s reputation. That is more than they were permitted to spend in the campaign itself. The level playing field created by Canada’s first election finance laws has thus been overturned. Ignatieff entered the campaign period as a team captain facing an opponent with six runs already on the board.

Perhaps with the safety of a majority the Conservatives will do what Liberal and Conservative governments have done three times previously: name several academic and political greyhairs to re-examine the entire electoral process, from voting restrictions to improving access for the two million overseas Canadians, the role of online voting, campaign finance and the basis for riding redistribution.

Harper was visibly bad-tempered and uncomfortable for the first half of the campaign, nowhere more than during the debates. Insiders blamed a lingering flu for his shaky early campaign performance; others offered more interesting psychological reasons. According to one former Tory insider, Harper appeared inappropriately angry and mean-tempered for an entirely different reason: he is deeply unhappy at the price he has had to pay for power, and at how little he has been able to deliver in the form of a conservative legacy.

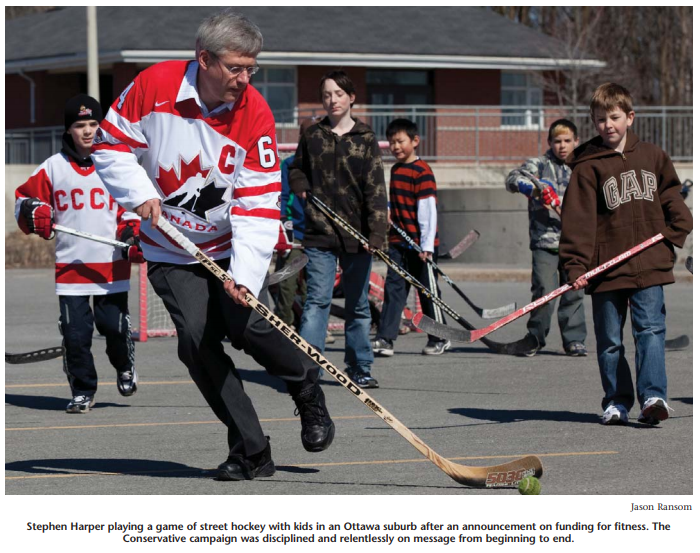

Harper found his feet following the debates, how-ever, and fell into a careful routine of early policy announcements, endless ethnic and small town media interviews and then a rousing appearance before a partisan crowd each evening. He will never be a great speaker or a charismatic political star, but in his fourth campaign Harper finally appeared comfortable in his skin, unflappable under attack and capable of a message discipline few politicians can master.

A criticism of Ignatieff, indeed of the Liberal Party since the end of the Martin era, has been its failure to redefine itself for a new generation in a new century. The comparisons of the 1993 and the 2011 Red Book platforms were painful, not merely because they revealed some golden oldies that had never made it into reality — child care being the most infamous — but also because they revealed how trapped in time the party remains. If the Liberals had been more disciplined in their use of the material, however, some of the damage of this campaign might have been avoided. The combination of Ignatieff’s stream-of-consciousness speaking style and Oral Roberts delivery meant that reporters could choose any one of many “bits” each night for a story. And they did.

In the final two weeks, Ignatieff stepped on his own story constantly. When he should have been hammering health care, he would add a story about education; when he was pounding his education passport story, he would get diverted once more into a Harper attack.

Ignatieff’s handlers clearly felt that if they could get under Harper’s skin, if they could repeat an attack so egregious often enough that he finally erupted, they would be halfway home. Harper is famous for a foul mouth, for lashing out at staff, ministers and candidates. But he is now a seasoned professional, and he knew that any flash of the famous Harper temper would be a campaignframing disaster. Having Laureen at his elbow was probably a wise, soothing element, as well as a finger in the eye of the Ottawa gossips who claimed his marriage was on the rocks.

Insiders always credit political ad campaigns with enormous power. Certainly two years of nasty attack ads, unanswered by the victim, savaged Ignatieff’s reputation. But that was an expensive opportunity that probably cannot be repeated. After all, it is not as if two-thirds of Canadians are sitting at home watching either CTV or the CBC from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. during an election. They are watching 500 channels and an infinite array of Web content, and much of it time delayed, or with commercials removed. The power of social media was probably overstated in this campaign; the Twitterverse remains small and inward-looking. But it is growing exponentially. I suspect that by Campaign 2015, the parties will be much more results-driven in their ad spends, and that is bad news for TV network ad salesmen.

If, as voters told our Ensight researchers, this election was just another spring storm, a snapshot in time forecasting little, what does the future hold? The list of possible outcomes — given our lottery-like election system — is almost as long as a piece of string. Given the limits imposed by old age, personal ambition and the heavy baggage of history, two or three seem likely to prevail.

The sovereignist movement is not dead. It may be in control in Quebec again within a year. It seems unlikely, though, that its curious federal cousin will be resurrected. It doomed itself to irrelevance by failing to renew its leadership or its message over nearly 20 years. There may be a son of the Bloc, but Quebec will remain a big prize in play for the three federalist parties in Election 42.

If the Liberals use the bittersweet gift presented them by Canadian voters of four free years to rebuild, effectively, if they avoid the temptation to go messiah hunting, study carefully where their unique political space is today and do the hard work of recruiting, rebuilding and refinancing their rusted shell of a political organization, then winning back a large chunk of Quebec and much more is possible. Sadly, early signals seem to indicate that, like a forever backsliding AA member, the existing party apparat cannot avoid one more binge fuelled by cheap leadership liquor. As one political journalist observed of the leadership posturing and fingerpointing only hours after election day, Liberals need to bravely slice off the leeches that affixed themselves to the ailing party in the Martin-Chrétien era.

There will be no early discussion of cooperation, let alone merger, with the NDP. The Liberals will probably need to be thumped one more time before the reality of the numbers sinks in. This may ensure that the Canadian Liberal Party joins its international cousins in the developed democracies as a minor political player, occasionally permitted the role of kingmaker between larger conservative and social democratic opponents, usually regarded as benign and slightly eccentric in the soap opera of political life. It was a point of pride for Canadian Liberals for much of the postwar era that they were alone in the world in maintaining political liberalism as a dominant force in politics. They might want to chat with German, French, British and Nordic Liberals about the lessons they have learned from decades in obscurity — and, better yet, how to avoid that slide.

There will be voices in the NDP who say, “Smash the Liberals!” Layton and Harper have motivated their troops often with such a battle cry. That would be a triumph of blood lust and history over common sense. British Columbia offers a stark lesson in why that forced polarization of political choice is rarely a good idea for progressives. The BC NDP, Dave Barrett used to mutter acidly, is the only social democratic party in the world that can win more than 40 percent of the popular vote and yet be defeated. A Canadian political spectrum that offers two and a half choices to voters is more likely to tilt to Conservative victories, simply because Tories would have sole ownership of their half of the spectrum. It was that lesson that drove Stephen Harper and friends to cram a political merger down the unwilling throats of many Progressive Conservatives.

Layton is likely to play a more subtle game than the hostile takeover with which some Liberals have been attempting to scare their skittish base. As New Zealand, Australia and the UK have all demonstrated recently, there is a range of options between political hostility and acquisition. The first is private and exploratory discussion of common interests between consenting political adults.

Layton is likely to play a more subtle game than the hostile takeover with which some Liberals have been attempting to scare their skittish base. As New Zealand, Australia and the UK have all demonstrated recently, there is a range of options between political hostility and acquisition. The first is private and exploratory discussion of common interests between consenting political adults. That process has already begun. Next might come a more public exploration of a progressive agenda, convened under academic or think tank auspices. Nonaggression pacts, seat division, shared candidate selection, common platform planks — all are living-together tools employed by left and centre-left parties elsewhere in the world, before they decide to walk up the aisle.

Of course, Harper will wag a finger and say, “There they go again, planning a secret coalition,” and many partisans on each side of the left/liberal divide will delight in highlighting difference and division. But as one Canadian pollster likes to say, “At some point the numbers talk to you.” The numbers in this case are that with Harper’s enormous advantage of a solid 75 to 100 seats in western Canada, and now a solid new base in Ontario, no division of the remaining spoils is ever likely to be successful in defeating him. The NDP is not likely to lose more than half its caucus next time out. The Liberals would then have to win every remaining seat to form even a minority government.

If Layton continues to grow in stature and political skill, his stretch from 103 seats to the next 50 is much shorter than the Liberals’. The Liberals are probably near their nadir as a federal caucus. Unless the party were to continue committing slow suicide — not a good premise on which to build strategy as an opponent — it seems unlikely it will come back with fewer than 40 to 50 seats in the next round, making a Layton-led majority tough. The Conservatives no doubt maximized their vote/seat efficiency in 2011, and the Liberals sank to their poorest conversion of support into MPs. It would be foolish to regard either benchmark as a forecast.

If the Liberals listen to their better angels, they will start with a clean slate and ask, “How can we best ensure our ability to help deliver a progressive agenda to Canadians?” It is not possible to see an answer that does not involve some form of cooperation with Greens and New Democrats, a strategy that appeals to independent voters, new Canadians and the nearly four out of ten Canadians — disproportionately the young — who feel so disenfranchised they once again voted for none of the above by staying home.

On the other hand, Layton will soon lay out an agenda and a work plan to give comfort to Canadians that he will follow in the tradition of statesmen such as Tommy Douglas and Allan Blakeney, who governed with enormous craft and skill and crushed the Liberal Party in Saskatchewan as a result. He will point out that New Democrats rescued Saskatchewan and British Columbia from crippling debts twice.

Many of his friends and colleagues expect Harper to step down as late as possible, in order to force his competitors to make their leadership choices first, and to give him an opportunity to groom the most impressive team of successors. Unlike any of the other leaders, he has a series of bright, seasoned young ministers who will be in the prime of their careers in 2014-15.

Harper will probably retire to the traditional post-prime ministerial role as statesman and corporate board member sometime around 2014, if he is wise. Canadians do not often grant third terms, and by some counts, he would be seeking a fourth term in 2015. He will have spent the intervening years attempting to solidly buttress his gains in Ontario and rebuilding in Quebec. His successor will need to find a message promising both continuity and renewal, never an easy pretzel stance in political life. Kim Campbell most spectacularly failed at it, but so, more recently, did John Turner, Paul Martin and Stéphane Dion.

Layton will have nurtured some of his improbable Quebec brood into fledgling political stars in the same period. He will have nudged most of the existing pretenders to his throne offstage in favour of players from a new generation. He will have cemented in voters and the media’s mind that the federal NDP is a follower of the Prairie tradition of progressive governance as his inoculation against attacks in Ontario over the party’s less successful experience in power there.

He will have found a way to marry the soft nationalist aspirations of his Quebec base to the somewhat skeptical New Democrats west of Thunder Bay. In so doing he will truly have built a new national political coalition capable of governing.

Or he won’t.

To achieve such a transformation of reputation and image and organization and political development is a Herculean labour. Having watched Layton’s performance for nearly 30 years, first Torontonians and then Canadians came only recently to see “Jack” with admiration, respect, even affection. It is a rare tribute when a politician gets to drop his surname: Tommy, Pierre and René are among the few. Layton has achieved his improbable transformation into the new guy through genuine political and personal growth. It is an unusual human being who continues to mature and develop beyond his or her 40s; most of us get stuck in grooves in which we glide until the end.

As a young politician, Layton was brash, often insensitive to colleagues, careless and quick to anger. Some credit finding the love of his life in his second marriage as the trigger for the change; others credit mentors such as Broadbent and Blakeney. His successful battle with cancer certainly added serenity and an ability to sort the trivial from the true. It is hard today to recall the snarling AIDs advocate on Toronto city-council, denouncing all who failed to share his anger at the plague sweeping through the city’s gay community, or the first-time federal NDP leader lashing out at Paul Martin as someone cruelly watching the homeless suffer and die. Smilin’ Jack, grinning like FDR on a train platform, brandishing his cane to admiring crowds, has little in common with that often irritating, sanctimonious earlier model.

Layton’s cool caucus management in the last Parliament — holding in check without alienating his monomaniacal Quebec deputy — stands in sharp contrast to the experience of Dion and Ignatieff and their regular clashes with their front bench. He likes to say he learned at the feet of two masters: his father, Robert Layton, who was Conservative caucus chair, and his father’s boss, the caucus management master of the past century, Brian Mulroney.

Layton also recovered more quickly than most of his colleagues from the bitterness of Ignatieff’s treachery in signing and then denouncing their 2008 coalition agreement. He established a working relationship with Harper, one that will no doubt continue in this Parliament. Unknown to most Canadians, however, is how broad and well nurtured are the new Jack Layton’s political networks. Academics, journalists, municipal and provincial politicians, environmental activists and musicians — they all get calls and emails out of the blue.

Like Mulroney, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, he has become a visceral people politician. Layton has shed his skin as an ideological scold and matured into the kind of leader who reads and then dominates a room in an instant; a personality about whom, following a brief encounter, tough union bosses and jaded activists alike buzz happily for days. Nonetheless, Tommy Douglas and Ed Broadbent learned similar skills, and Canadian voters broke their hearts several times. The odds against a social democratic party alone in power in government are not trivial.

A Saskatchewan New Democrat explained his party’s survival in power over many decades, set against the far more troubled experience the party faced in British Columbia and Ontario, this way: “Saskatchewan doesn’t really matter in the scheme of things. Corporate Canada didn’t mind socialists having this plaything on the prairies. Manitoba mattered only slightly more and less now than in Ed Schreyer’s day. But BC, that was different: there’s billions of dollars in the rocks and logs business at risk there. And Ontario! Now that was serious — no way Big Capital was going to allow lefties to capture the engine room of Canadian wealth and prosperity.”

Looking forward to 2015 — an eternity of almost infinite possibilities of change — several new realities still seem bankable. The first is that each party will be headed by new men or women. And it seems likely that the smart parties will jump a generation in choosing their new leaders. The Liberals will resolve their unseemly wrangling over an interim leader, and unless their collective political judgment was destroyed along with half their caucus on election night, they will have given themselves at least 18 to 24 months to rebuild and reach out for a new leader. I would be surprised if any of the names currently being considered survive that process. The Liberal Party’s renewal after major defeat has almost always involved reaching out to external figures. Some on the right of the party salivate over the prospect of Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney, for example.

Many of his friends and colleagues expect Harper to step down as late as possible, in order to force his competitors to make their leadership choices first, and to give him an opportunity to groom the most impressive team of successors. Unlike any of the other leaders, he has a series of bright, seasoned young ministers who will be in the prime of their careers in 2014-15: James Moore will be 39, James Rajotte, 40, and Jason Kenney, 47, among several others. An outsider is also possible, but less likely given the party’s intense bonding experience following the 2003 reconciliation of Canadian conservatism.

If Harper has successfully navigated the economic challenges ahead, if he delivers free trade agreements with Asia and Europe, thaws the American border restrictions and stimulates foreign direct investment in our resource and technology sectors, all the while taming the deficit, holding down taxes and spending, with stronger new jobs and productivity numbers, a strong dollar and low inflation — a political trifecta not seen since the days of C.D. Howe — he may be tempted to stay and challenge the records of Trudeau and King in office.

Jack Layton may now feel compelled to conduct one more campaign, having taken the party so far in less than 10 years. If his health does not interfere, he may join Tommy Douglas and David Lewis in fighting their most successful campaigns at the very end of their careers. He will be working hard to spot and develop leadership talent from among those elected this time, in case events require a handover. Do not be surprised if that small group of pretenders includes more than one first-time Quebec caucus member, and not his current deputy.

If Jack Layton is able to shape a government in waiting similar to the one Allan Blakeney assembled to tackle the fiscal mess left to him by Ross Thatcher, or the strong capable front bench and backroom advisers that Roy Romanow and Gary Doer built as the foundation for their long successful periods in government, he will be well placed to solidify the NDP’s position as the number two party for a decade or more, capable of realistically running for office for the first time in a century of social democracy. If he successfully manages his green and potentially disputatious young Quebec caucus, bringing their ideas and vision into national politics in a manner that reassures English Canadians, he will be following the success of Trudeau, Mulroney and Chrétien in performing such a considerable feat. And if he fails, his caucus will be cut in half, and his stay in Stornoway will be limited to this one unlikely term.

But it is the Liberals who hold the greatest mystery about their impact on the future of Canadian politics. Western democracies today offer little political space to those whose vision is simply “centrist.” This seems paradoxical since politics rewards compromises at the centre that are capable of being supported by the largest and strongest coalitions of interest. As Conservative sage Tom Flanagan has observed, parties serious about government, like stock markets, always tend over time to regress to the mean. They seek the centre because that is where the movable voters live.

If the Liberals allow themselves to be dragged to the left to compete with the NDP, both the NDP and the Tories will smile, for such a strategy puts blue Liberals at risk and allows the NDP to sneer that Canada does not need two progressive parties, especially one that is a relic of another era. The risks of a tilt rightward are the mirror nightmare. The Liberal ownership of the title as the only successful managers of the national question began to weaken under Brian Mulroney and further eroded under Stephen Harper, and now Jack Layton will claim he has won that role.

It will be in the wake of election night 2015 that the three parties may need to find a way to turn three into two, as least for the purposes of governing if the vote produces a new minority. As the UK election results last year demonstrated, it is not entirely clear who, on the morning after, will wake with whom as the strange bedfellow — or in which bed.

Photo: Shutterstock