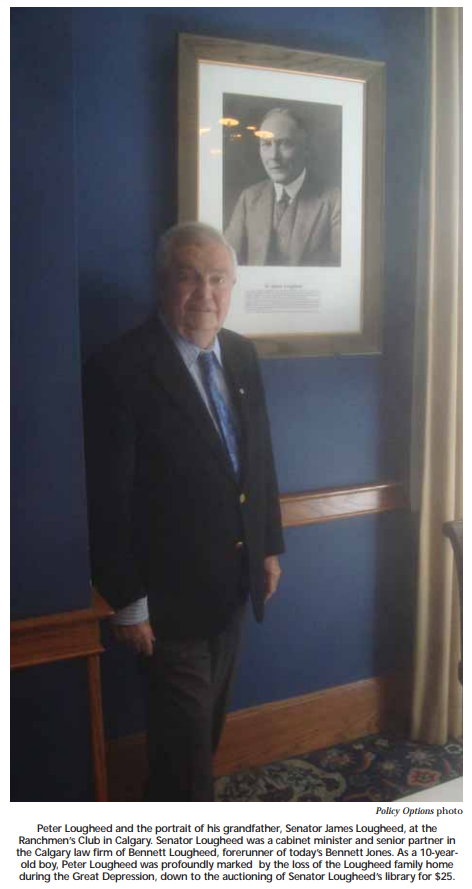

The Dirty 30s were not kind to Alberta. The Great Depression had ravaged farms, families and fortunes. In Calgary, as his grandson watched with foreboding, the estate of Senator Sir James Lougheed, a pillar of the community (and instrumental in Alberta’s becoming a province in 1905), was auctioned for taxes. The contents of the stately Beaulieu were going for a pittance. Suddenly from the back corner, as the late senator’s entire library sold for $25 a young voice cried, “That’s a steal!”

It seemed so unfair to a 10-year-old Peter Lougheed, witnessing the loss of Beaulieu and the loss of his own family’s home during the Depression. There was something wrong with a system that would let this occur. How did it happen, he wondered. Could it have been avoided? How could we run things differently?

It was a pivotal moment in the life of the man who 30 years later transformed Alberta from an agrarian hinterland into the most dynamic province in Canada and restored a pride of place, a positive spirit and promise of the future.

Like Peter Lougheed, Albertans of his generation and the one that followed took many lessons from the Great Depression. They learned the value of perseverance, determination, hard work and being a good neighbour. Those times also taught self-reliant Albertans loyalty, the benefit of working together, to be grateful for their blessings, and to do the best with the gifts they were given. Peter was taught at an early age to work hard, be positive, be self-assured and believe in himself. At home, “excellence in any pursuit was not only to be desired, it was expected. Failure was not to be tolerated.” Success on the playing field, at school and socially gave Peter confidence and enthusiasm for getting the most out of life and making it better.

He personified an Alberta can-do spirit of independence, of helping your neighbours, of volunteerism, of striving to do better and contributing to the community. It was about remembering the past with optimism for the future. He learned the worth of teamwork, loyalty and commitment on the football fields of Calgary with the West End Tornadoes in high school and later playing halfback with the Edmonton Eskimos of the Canadian Football League. He would later engender that same collegiality, loyalty and team spirit in his caucus team in the Alberta Legislature.

A unique ability to manage his time and energy was also apparent from an early age. Diligently and successfully combining scholastic achievement, sports and an active social life, he was always the organizer, the visionary, the positive force his peers turned to for leadership. In a presage of things to come, he established the first student council while at Central High School in Calgary — and became its first student president. During law school at the University of Alberta (while courting his future bride, soulmate and confidante, Jeanne Rogers), he was elected president of the Students’ Union. Ivan Head, who ran against Lougheed, was quoted in David Wood’s The Lougheed Legacy as saying, “It was another example of his first-rate organizing talents and an early demonstration of his ability to get votes.”

Peter’s enthusiasm and energy were contagious. Friends, teammates and, later, those who worked with him in business and his early law practice were captured by his positive spirit. He saw value in others and the good in people, and he encouraged the best of those around him.

It’s an Alberta spirit alive today in our western heritage and values and is reflected in the brand of the Calgary Stampede. As a former volunteer, committee chair and board member, Peter emulated the core values of the Calgary Stampede brand: western hospitality, integrity, pride of place and community.

Peter articled with the law firm of Fenerty, McGillvray and Robertson (now FMC) in Calgary before continuing his education. While taking an MBA at Harvard, he worked briefly at Chase Manhattan Bank in New York and had a summer job at Gulf Oil in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a city that knew the booms and busts of an oil economy. Returning to Calgary in June of 1956, he joined the Mannix Company (now Loram International) honing his legal and negotiating skills and contributing to the company’s international success. In eight years under the tutelage of the venerable but demanding Frederick C. Mannix, he rose to vice-president and gained a worldly knowledge of international business and finance that would serve him well in the role he was destined to assume.

With two partners, Lougheed opened a private law practice in Calgary in 1962, serving entrepreneurs, engineers, geologists, risk-takers and builders. It was still the Wild West, where deals were done with a firm handshake, but then sent to the accountants and lawyers to be “papered.” Ethics, integrity and reputation were still paramount but increasingly business and life in urban Alberta was more sophisticated, faster moving and cosmopolitan.

Like Peter Lougheed, Albertans of his generation and the one that followed took many lessons from the Great Depression. They learned the value of perseverance, determination, hard work and being a good neighbour. Those times also taught self-reliant Albertans loyalty, the benefit of working together, to be grateful for their blessings, and to do the best with the gifts they were given.

There was a growing sense, particularly in the cities, that growth was stifled by a slow and inefficient bureaucracy in Edmonton, insufficient infrastructure, outdated or old-fashioned process systems and a feeling that we were falling behind the times. Alberta could do better, a thought Peter Lougheed had held for a long time.

The province was changing, with urbanization, commercialization and the golden age of television opening more eyes to a faster-paced, modern world and the social revolution of the 1960s. Albertans began to embrace new ideas and a more youthful, positive outlook. At least in the cities. Rural Alberta was not as eager to accept or adapt to change.

It wasn’t just a rural-urban split that threatened 50 years of homogeneity in the Alberta electorate. Immigration, changing social values, the role of women, declining church attendance, materialism, many of the same influences that were changing voting patterns in other provinces, foreshadowed a new era of Alberta politics. Were we nearing the end of one-party politics in Alberta?

In mid-1960s Alberta, it was a little early to tell and few, if any, even asked the question. There was sufficient discontent with the party in power that urban Progressive Conservatives at least, after a 50-year hiatus, determined it was time they got back in the game.

They approached a young energetic lawyer with the heritage of Sir James Lougheed, a Harvard MBA, who was photogenic and articulate, and seemed the perfect choice to do just that.

Without much of a base and no seats in the Alberta Legislature (Conservatives had been shut out in the last election and hadn’t elected a handful of MLAs since 1935) the PCs must have seemed less of a perfect choice to Lougheed. The visionary “Big Four” cattle barons and business leaders who endorsed and supported Guy Weadick’s grand vision of putting Calgary on the map by creating The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth anted up $100,000 in support of the inaugural 1912 Stampede. A half century later, business and community leaders, friends and long-time Conservatives supported a fledging Lougheed Club with $100 contributions to provide funds to rebuild the Progressive Conservative Party and encourage Peter Lougheed to lead it.

It was less than a year until the vacant provincial PC leadership was to be filled but if, as many close to him had felt since his childhood, a future in politics was part of his life plan, this was the time. Lougheed considered the challenges and thoughtfully developed a plan to meet them. With the support of those lifelong friends, former teammates, university colleagues and business associates, he contested and won the provincial Conservative leadership and began to develop a positive plan and prepare for the upcoming election.

The Lougheed team exploded onto the scene in 1967. From relative obscurity in the province, the young and charismatic Tories brought energy and enthusiasm to the spring election campaign. They turned door knocking and “meeting the people” into an event. In the cities, an advance team of door knockers would get the perspective voters to the door, and upon opening it the constituents would see an athletic Lougheed bounding up their front step, the street buzzing with supporters and a family station wagon towing the scene-setting LOUGHEED billboard on a trailer. In the rural areas and smaller towns, the Lougheed bannered bus, now a staple of campaigns, would roll in with music playing like the circus coming to town. Slightly embarrassed by it, Peter had to admit it did attract attention to the new PC

Party and brought a vibrancy and excitement to the campaign.

As the campaign bus rolled to every corner of the province, he was getting to know rural Albertans, their aspirations and anxieties — life on the farm was changing, too. Peter also saw a special quality of life that inspired him, not just the natural beauty of the province but the freedom and way of life they cherished. He listened, learned and soon realized he’d have to demonstrate a new inclusive vision of Alberta if he were to restore common ground among Albertans and represent a united Alberta voice.

The whirlwind 1967 campaign resulted in a breakthrough 6 seats for the Progressive Conservative Party, 55 for the governing Social Credit Party, 3 for the Liberals and 1 independent. Lougheed was elected in Calgary West with the largest majority of any candidate and became Leader of the Opposition. The “original six” PC MLAs were a remarkable group. Hugh “Doc” Horner, physician and surgeon, had won four successful federal elections when he resigned from Parliament in 1967 to run provincially. A highly respected champion of rural Alberta, he was a savvy, shrewd politician in the Legislature. Don Getty, future premier, was best known at the time as a quarterback with the Edmonton Eskimos; he was a successful financial and oil company executive who brought business acumen and sound judgment. Lou Hyndman, an Edmonton academic and lawyer who had a solid grasp of parliamentary procedure, became opposition house leader. David Russell, a softspoken architect and former Calgary Alderman, brought a gentle balance to the aggressive team. Len Werry, personable and enthusiastic, the antithesis of the stereotypical accountant and business assessor, became the labour spokesman in the new caucus. Together they provided a positive alternative to the 32-year-old government, and over the next four years they built a party and platform Albertans would see as a government in waiting.

Within days of the 1967 election, Peter brought the “team” together — the first caucus meeting of the Lougheed Conservatives. In attendance were not only the six new members of the Legislative Assembly, but the defeated Tory candidates from across Alberta. Peter thanked them all for their commitment and gave every one of them a feeling that they, too, were a valued part of the team and that their ideas, involvement and the vision of Alberta’s future they shared were important to him. From that meeting on, through four successive Lougheed governments the caucus, his team, was key. As coach, captain and team leader he was accessible, understanding, clear in expectation and always had his “players” do more than they thought they were capable of. He was always in their corner and none wanted to let him down. Peter wanted to know what they thought and why. As the uniform views of the old Alberta faded, input and ideas and consensus from a broader circle became increasingly important. Everybody had value and had something positive to contribute. The team spirit and mutual respect were infectious and inspired a loyalty rarely felt in politics. At a late-night social gathering years later when the attending PC MLAs, staffers and supporters burst into a spontaneous version of the Sister Sledge hit song “We Are Family,” it felt entirely appropriate and genuine.

He learned the worth of teamwork, loyalty and commitment on the football fields of Calgary with the West End Tornadoes in high school and later playing halfback with the Edmonton Eskimos of the Canadian Football League. He would later engender that same collegiality, loyalty and team spirit in his caucus team in the Alberta Legislature.

The “original six MLAs” entered the Legislature in the fall of 1967 with purpose and a plan. They were respectful, tactful, well prepared and diligent. Albertans showed renewed interest in what was going on “under the Dome” of the Alberta Legislature building. The Lougheed team brought constructive criticism, tough questions, thoughtful debate and, against the objections of the Ernest Manning government, these upstart Conservatives attempted to introduce Legislation from the opposition benches.

The highly regarded Speaker of the Legislature, Arthur Dixon, after consultation with the legislative clerk and legal counsel, reluctantly ruled the unusual procedure was in order. Led by Alberta’s first environment Bill, a series of 21 further bills would flow from the Opposition in the first term. Of course none of them ever passed but they commanded attention by proposing new ideas and resolution to the concerns of Albertans. The positive performance also garnered media attention and signalled a serious alternative in the making.

Lougheed once spoke of the “five hats” a party leader had to wear, referring to the roles he was expected to play or was responsible for. He was at once the leader in the Legislature and chairman of caucus, leader of the party, chief party organizer, head recruiter of candidates and staff, and chief fundraiser. During that first term, he mastered all five, leading the caucus, developing the policy platform, building the party organization, recruiting candidates and stocking the campaign war chest.

It began with vision and a plan. Aware of Alberta’s history, cognizant of changes underway and looking strategically down the road, Lougheed developed a synchronized critical path where all component parts would come together — first in the 1971 general election and later with revolving 5-, 10-, and 15-year forward-looking plans for Alberta.

As the Lougheed Tories planned for the future, a burgeoning generation of baby boomers was coming of age. Even a casual glance toward provincial politics revealed a striking contrast between the government of their parents and the new opposition. Against the boundless energy of the Lougheed Conservatives, the Social Credit government looked earnest but tired. Not so much old, but old-fashioned. In fact, when Premier Ernest Manning retired in the fall of 1968, the average age of his MLAs was just 54; the average age of Lougheed’s Progressive Conservatives was under 40.

The Conservatives won the by-election in the seat vacated by Manning and before the next election was called won a second by-election and were joined by Liberal MLA Bill Dickie and independent member Clarence Copithorne, who crossed the floor.

The momentum continued outside the Legislature. As the party organization grew and candidates were recruited, the policy platform was developed. By the spring of 1971, a complete government action plan had evolved with member input and inclusive party policy conferences colligated by the brilliant policy committee chair, Calgary lawyer and old Lougheed friend Merv Leitch. Leitch had vied with Lougheed for top honours at law school and would become attorney general in his first cabinet and later energy minister.

When Manning’s successor, the lacklustre Harry Strom, called a snap election in July 1971, Lougheed was prepared with solid constituency organizations, a slate of credible candidates, a campaign plan and (just in case) a blueprint for government. While Strom may have had some idea of what lay ahead (as post-election Lougheed staffers discerned from Social Credit polling data found discarded in the former premier’s office), he could not have imagined what was coming in the campaign of 1971.

As if hearing a starter’s pistol, as soon as the writ was dropped, wellprepared Conservative volunteers were dropping preprinted election brochures in mailboxes the very evening that Premier Strom called the election. Conservative billboards, bus benches and lawn signs began to appear the next day.

From the 1930s, the Social Credit message had been for the most part delivered from pulpits, disseminated by affiliated religious groups across the province and supported by the weekly radio broadcasts of the Back to the Bible Hour. The voices of first William Aberhart and later Ernest C. Manning, had been heard across the Prairies each Sunday evening for 40 years. In many rural areas (or for city folk driving home from a weekend of skiing in the Rockies), it was the only thing you could get on the scratchy AM band of the car radio.

Radio advertising was and remained Social Credit’s principal campaign vehicle. It was now seven years since Marshall McLuhan had published the iconic Understanding Media — in 1971 Peter Lougheed knew the medium was television and he was a star. He had not only cultivated the media over the preceding four years but had studied and cultivated the medium. The Progressive Conservatives spent 85 percent of their media budget on television in the 1971 campaign. The Socreds stuck with radio.

Lougheed’s campaign was never critical of the Social Credit government but offered a positive alternative. The PC message, “Guideposts for the Future,” was one of diversification, economic development and maximizing the return to Albertans from their nonrenewable oil and gas reserves. The vibrant, progressive message saturated the province and the positive Lougheed image captivated Albertans.

In the final week of the campaign, a symbolic three-letter word was appended to the Conservative billboards, lawn signs and television commercials. NOW was Alberta’s time. On August 30, 1971, Lougheed’s party won 49 of 75 seats and became Alberta’s first Progressive Conservative government.

Lougheed was an early riser and often began his day with a run in the clear morning air. It was his unencumbered thinking time. Though his thorough preparation had produced a clear transition plan and a detailed blueprint for governing, the results of the election would require quiet reflection. Changing voting patterns and the distribution of seats confirmed the growing heterogeneity and demographic divergence he had sensed as he crisscrossed the province during the election campaign. Clearly this was not the monolithic, uniform electorate enjoyed for decades by the previous administration. The new premier had this in mind as he considered the appointment of his first cabinet.

There were eight ministers in William Aberhart’s first cabinet, nine in the first Executive Council of Premier Manning. Decisions of their governments were made solely by the premier and cabinet, who in the largely agrarian, homogenous Alberta of the time could no doubt reflect and represent the sentiments and opinion of the broader population, without much need of consultation with the electorate (or their MLAs). By 1971, the Social Credit cabinet had grown to 15 ministers who likely presumed that they, too, could adequately represent the views of all Albertans, but in contemporary Alberta, as much as the old leadership believed that all Albertans thought the way they did and shared their conclusions, it just wasn’t like that anymore.

To stay “in touch” with Albertans and better represent a wider range of views and form a broader consensus, Lougheed increased the cabinet to 22 ministers representing the apparent urban-rural differences (notably with the strength of his “rural lieutenant” and deputy premier, Hugh Horner) as well as the increasing demographic diversity of the province.

Lougheed once spoke of the “five hats” a party leader had to wear, referring to the roles he was expected to play or was responsible for. He was at once the leader in the Legislature and chairman of caucus, leader of the party, chief party organizer, head recruiter of candidates and staff, and chief fundraiser. During that first term, he mastered all five, leading the caucus, developing the policy platform, building the party organization, recruiting candidates and stocking the campaign war chest.

Instinctively Lougheed knew he would also rely heavily on the innate perceptions, regional knowledge and opinions of his caucus.

During the Manning administration, the Legislature sat for only two months a year. The Social Credit caucus did not meet when the Legislature was not in session. The Lougheed caucus enjoyed a closer relationship.

During the legislative session, the entire Progressive Conservative caucus met with the premier every day before Question Period to review current issues. Each Thursday they gathered for a half-day session at the stately Government House. A few kilometres from the Legislature in Edmonton, the three-storey sandstone mansion had been purchased by the government in 1910 to house the lieutenant governor of Alberta.

The home was lost to the Queen’s representative and sold during the Depression (in the same year as the loss of the Lougheed family home in Calgary). The Aberhart government attributed the closure of Government House to necessary cost-cutting measures. Many suspected it had as much to do with the refusal of Lieutenant Governor John Bowen to grant Royal Assent to two Social Credit bills that would have placed the province’s banks under government control and a third, the Accurate News and Information Act, that would have forced newspapers in Alberta to print rebuttals to stories the cabinet objected to. The building was reacquired in 1964 and subsequently used for ceremonial events and as a conference centre for the government.

Gathering at Government House gave caucus meetings an air of importance and significance. And significant they were to the new premier. Lougheed’s insistence on random seating around the large circular table in the third-floor conference room signalled a parity among members and established that in caucus all voices were equal. In Lougheed’s government, the caucus was paramount. He made it clear from the first meeting that in the making of key decisions, caucus overrides cabinet.

It was here that consensus was reached, where decisions were made. Caucus was the sounding board as well as a source of new ideas and proposed legislation where views from every part of Alberta, as diverse as the province itself, were shared in thoughtful, civil discourse and all were encouraged to express their opinions. The team came together and gave the premier confidence that decisions reached reflected a true and democratic Alberta consensus.

On the practical side, with any differences or difficulties worked out in caucus when a new program or legislation was introduced in the Legislature, there wasn’t much room for criticism. The opposition found little to disagree with. Once observing the placid Alberta Legislature in action from the press gallery above, journalist Allan Fotheringham would quip, “It’s like a nunnery in recess.”

And that’s just the way Premier Lougheed liked it. No surprises.

The solidarity and confidence of his caucus would soon become an even greater asset as was his timely modernization and control of the administration and workings of the Alberta government.

As the Lougheed Tories planned for the future, a burgeoning generation of baby boomers was coming of age. Even a casual glance toward provincial politics revealed a striking contrast between the government of their parents and the new opposition.

Creating a modern Alberta in 1971 would require the implementation of efficient business systems, processes and controls where none existed. In the Executive Council offices, for example, there were no minutes or agendas of previous Cabinet meetings — none were taken. The only records of Cabinet meetings were of orders-in-council. There were no formal decision-making processes apparent. Lougheed brought contemporary management systems, fiscal controls and oversight to the Executive Council that would provide a basis for the transformation of the moribund administration he had inherited. He turned to trusted professionals, many from the private sector, to enhance or depose the existing bureaucracy.

Among the first appointments were respected former banker and Mannix executive A.F. Chip Collins as deputy provincial treasurer, and David Wood, a writer and trusted public relations counsel who would create the Alberta Public Affairs Bureau to organize all government information services. During his first term, Lougheed replaced 70 percent of the deputy ministers from the previous government and established the competent, effective and responsive administration he would rely upon in the years ahead.

Foresight and perhaps prescient planning were also reflected in early legislation of the new government. It is sometimes forgotten, for example, that the Lougheed government had already passed legislation increasing royalties to the province before the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries cut exports in 1973, quadrupling the value of Alberta’s resources and setting off events that would demand all of the talents of the new premier, his team and his administration.

In the battles to come, Lougheed would be well served by the solid foundation he had built in Alberta and the loyalty he inspired. His base secure, he could focus on external challenges as they arose. He gave Albertans the confidence to believe in themselves as full and equal partners in our Confederation. At the 1981 constitutional conference, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau asked the First Ministers rhetorically, “Who speaks for Canada?” Lougheed replied, “We all do.”

The Canadian Encyclopedia presents a fitting tribute: “Lougheed has become a Canadian icon, respected for the values he brought to his political career: competence, astuteness, integrity and an unwavering commitment to the welfare of the people of Alberta and Canada.”

It’s not just history that will remember Peter Lougheed fondly, but all those who have known him along the way.

Photo: Shutterstock