Canada’s school system was turned upside down by the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the first phase, the system-wide shutdown was much like a power outage that left students and parents in the dark and educators scrambling to master unfamiliar forms of education technology. Making radical readjustments, in lockstep with public health directives, upset the normal order in Canadian K-12 education.

What emerged to fill the vacuum was what online learning expert Michael K. Barbour aptly termed “triage” schooling and “remote teaching in an emergency situation,” aimed at stabilizing the shaken system. Three months of slapped-together home learning produced predictable results: bored and tuned-out students, exhausted parents and exasperated teachers.

Building back the disrupted and damaged school system will involve confronting squarely the fragility and limitations of the current structure. Education’s “iron cage” — a bureaucratic organizational system first diagnosed by German sociologist Max Weber that traps individuals in a structure driven by technological efficiency, rational calculation and control — was exposed during the COVID-19 shutdown, and we came to see how dependent students, teachers and families are on directives from provinces and school districts. Cage-busting leadership will be required to transform our schools into more autonomous social institutions that, first and foremost, serve students, families and communities.

The bureaucratic education state in crisis

The centralized and overly bureaucratic school system described in my new book, The State of the System: A Reality Check on Canada’s Schools (McGill-Queen’s University Press), proved to be vulnerable and ill-equipped to respond to the massive upheaval of the pandemic. Instead of rising to the unexpected challenge, provincial school leaders took refuge in clinging to comfortable structures and ingrained policy responses, such as delaying e-learning implementation until all students had access to technology and the internet. When the school year was over, at least a quarter of all students had gone missing and were unaccounted for in Canadian public education.

The modern bureaucratic education state has a fundamental problem, and its roots run deep. Since the rise and expansion of this system over the past hundred years, public education in Canada has grown far more distant and much less connected with students, families, teachers and communities. Our public schools, initially established as the vanguard of universal, accessible, free education, have lost their way and become largely unresponsive to the public they still claim to serve.

Today’s schools have been swallowed up by provincial ministries and regional school authorities. Putting students first has little meaning in a structure that gives priority to management “systems,” exemplifies top-down decision-making, thwarts community-based schools and processes students like hamburgers in a fast-food operation. Graduation rates have risen so dramatically that high school diplomas are awarded to virtually anyone who meets attendance requirements.

The system, originally conceived as a liberal reform enterprise aimed at expanding mass schooling and broadening access to the populace, largely achieved its goals twenty-five years ago. Having achieved near-universal access, school authorities in the 1980s began to pivot toward introducing bureaucratic managerialism in the form of “instructionally focused education systems.”

In a North American wave of structural reform, the systematizers saw the “incoherence” of instruction from one classroom to another as a problem and teacher autonomy as an obstacle to further modernization. School change came to mean replacing didactic instruction, knowledge-based curricula and the teaching of basic skills, while embracing “ambitious instructional experiences and outcomes for all students.” At the school district level, it was reflected in new forms of school consolidation aimed at turning loose aggregations of schools into school systems.

Today’s central administrative offices, layers of administration, big-box elementary schools and supersized high schools all testify to the dominance of the trend. Elected school boards, a last vestige of local education democracy, are now considered simply nuisances and fast becoming a threatened species. Voicing concerns about the state of our public schools can be exceedingly frustrating – and, more often than not, an exercise in futility. Parents advocating mathematics or reading curriculum reforms, families seeking improved special-needs programs, or communities fighting the closure of small schools regularly hit brick walls.

How to take back our schools

The system, as exposed during the COVID-19 disruption, is not working for students or teachers in the classroom. Educational gurus spawned by the school improvement industry have succeeded not only in commandeering school districts, but in promoting a succession of curricular and pedagogical changes floating on uncontested theories and urban myths. This trend is most visible in the development and provision of resources by commercial purveyors closely aligned with “learning corporations,” curriculum developers and faculties of education. Challenging unproven progressive pedagogical theories will be essential if we are to base teaching on evidence-based practice and what works with students in the classroom.

Top-down decision-making, educational managerialism and rule by the technocrats has run its course. Rebuilding public education needs to begin from the schools up. Putting students first has to become more than a hollow promise. It will require structural reforms, including community-school-based governance and management.

A new set of priorities is coming to the fore: put students first, democratize school governance, deprogram education ministries and school districts, and listen more to parents and teachers in the schools. Design and build smaller schools at the centre of urban neighbourhoods and rural communities. It’s not a matter of turning back the clock, but rather one of regaining control over our schools, rebuilding social capital and revitalizing local communities.

Re-engineering the system has never been more urgent than it is in the wake of COVID-19. For that to happen, the walls must come down, and those closest to students must be given more responsibility for student learning and the quality of public education. The time has come for us to take back our schools and chart a more constructive path forward.

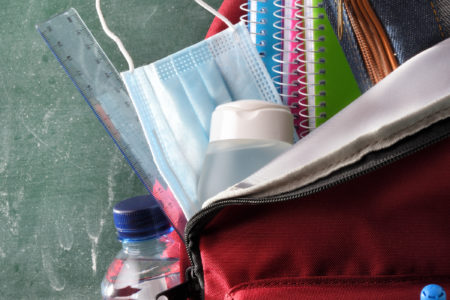

Photo: Students arrive at Dartmouth High School in Dartmouth, N.S. on Sept. 8, 2020. Classes for the new school year are starting on schedule after an extended break due to the COVID-19 pandemic. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Andrew Vaughan