The first time I ever heard of the term spiritual abuse was during a therapy session. As an intergenerational survivor of the Canadian Indian residential school system and the notorious Sixties Scoop, I thought I had managed to discuss just about every type of violence in my ongoing therapy sessions. Spiritual abuse, however, was a novel concept. Gradually, my understanding of the term helped provide me with a much-needed vocabulary that I used to better understand my and my family’s relationships to the past. The words “God wanted this to happen” took on a greater meaning and purpose when considering how spiritual abuse operated within the broader context of settler-colonial Canada.

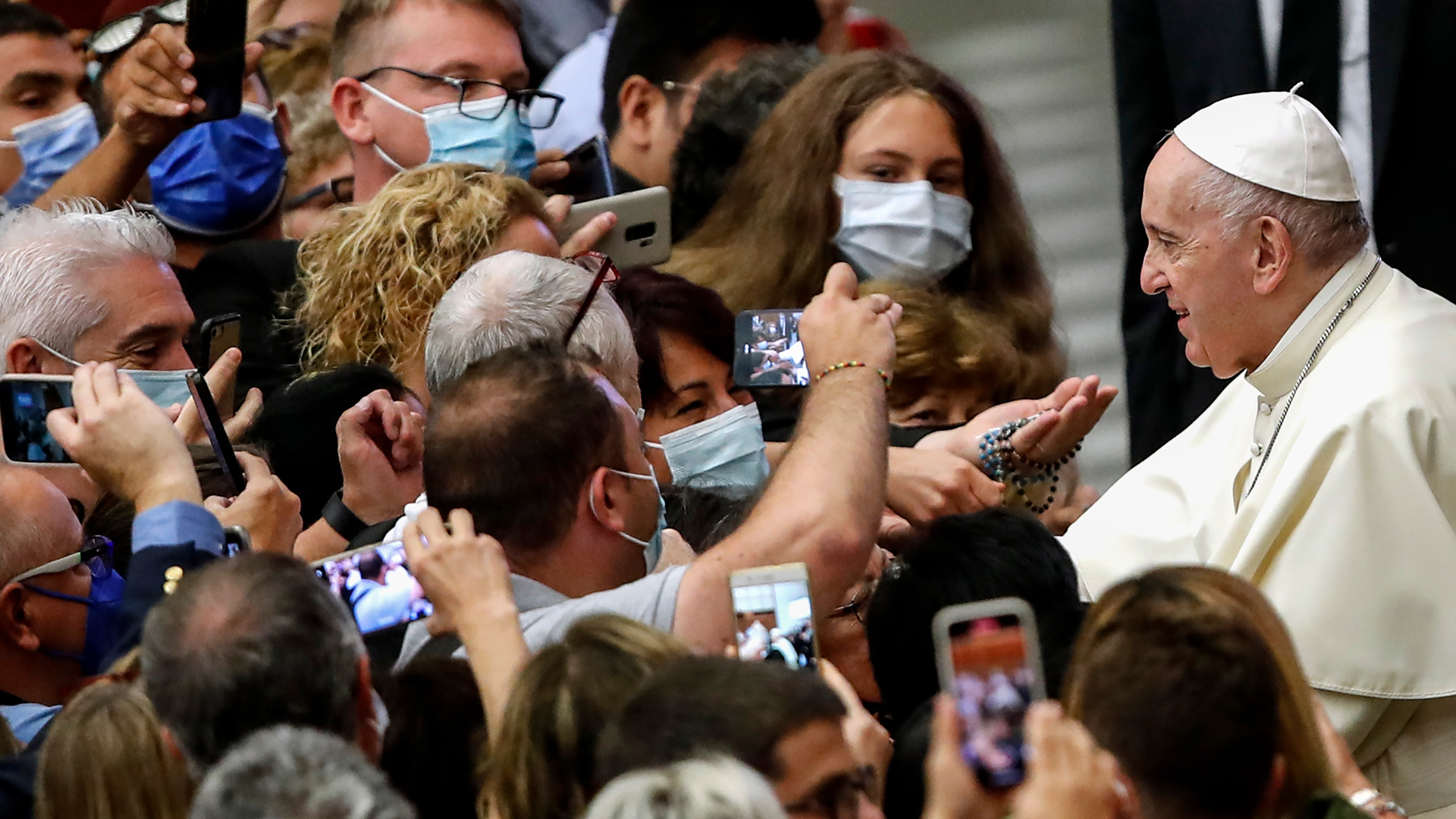

It was not long before my identities as a survivor and scholar intersected. As a doctoral student studying the relationship between violence and the Canadian settler-colonial state, I was fascinated by the new term. In exchanges with my peers, I soon found out that I was not alone in my lack of understanding of the concept. With news that Pope Francis will visit Canada, there needs to be a greater emphasis on the ways that the Catholic Church negatively impacted Indigenous spiritual practices. Indigenous groups will travel to the Vatican for a private audience with the Pope ahead of his proposed visit to Canada, the date of which hasn’t been set yet.

Spiritual abuse is complex and multi-faceted, and there have been numerous definitions offered by the research community. At its core, spiritual abuse involves the use of coercion within a spiritual context. Coercion can range from the use of spiritual and religious practices to justify censorship, humiliation, manipulation, harassment, forced conformity or forced forgiveness of abusers, and physical and sexual harm.

Spiritual abuse becomes a way of engaging in violence while simultaneously hiding any violent implications of that violence. This occurs by emphasizing the good intentions of the violence enacted. Spiritual abuse was a key mechanism of genocide in the Canadian context.

Spiritual abuse became a type of language used by the settler-colonial state – a state built on the displacement of Indigenous Peoples – to justify historical and ongoing violence against Indigenous people. An appeal to religion was an act of hiding the atrocities committed.

The appeal to religious morality created a black and white template for determining who was good and evil in Canadian society. Political and religious leaders who appealed to a Christian moral sensibility paved the way for spiritual abuse to be used as a way of codifying the evil and the righteous in Canadian society. It created a narrative that cast Indigenous bodies as evil and in need of discipline and control. These perceptions continue within contemporary Canadian society as Indigenous people face disproportionate levels of incarceration.

More broadly, spiritual abuse was part of assimilation. Just as one can leave behind their sinful ways and become Christian, so too one can leave behind their Indigenous heritage and become part of mainstream white Canadian society wherein civility and Christianity are synonymous.

The residential school system stands as an important source of spiritual abuse. These schools were funded by the government but run by churches. The majority were run by the Catholic Church. Spiritual abuse occurred with the restriction of Indigenous spiritual practices and the coerced conversion of Indigenous children to Christianity. In essence Indigenous spiritual practices were believed inferior to Western ones.

Residential schools broke the spiritual connections between children and their families, cultures and nations. These schools were places where the practice of Indigenous spirituality was prohibited. According to the 1996 report by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, “Aboriginal children learned to despise the traditions and accomplishments of their people, to reject the values and spirituality that had always given meaning to their lives, to distrust the knowledge and lifeways of their families and kin. By the time they were free to return to their villages, many had learned to despise themselves.”

There have been calls to the Pope to apologize for the role of the Catholic Church in the residential school system in Canada. It is also one of the 94 recommendations contained in the report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has personally asked Pope Francis to make an apology. So far, Pope Francis has refused.

Conversely, in 2019, the Anglican Church of Canada issued an apology for the its role in inflicting spiritual abuse on Indigenous Peoples. What is more, the Catholic Church spent millions of dollars meant to be directed at residential school survivors. Overall, the Catholic Church could learn lessons from the Anglican example and forge ahead with reconciliation in Canada by making apologies and restitution for its history of spiritual violence.