In the two years we’ve been dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s become clear just how precarious the social positioning of disabled people really is. Now, with a loosening of health protocols and cases on the rise again, we, as disabled people, have serious concerns for our safety.

Our concerns were many during COVID’s previous waves, and they linger as we face another. They included discussions that people with disabilities could potentially be denied health care should there be a surge in serious cases. As well, many of us wrestled with limited access to medical care, lack of access to vaccination sites and limited protection for the immunocompromised, particularly now that the masks are coming off. As a group, we have found our concerns largely overlooked, ignored or dismissed by those in positions of power. For disabled people, this lack of policy signalled once again just how invisible we are.

And yet, we shouldn’t be.

Disabled people are the world’s largest minority. There are more than one billion disabled people worldwide and we make up more than 20 per cent of the working-age population in Canada. Yet, we are often treated like a chronic add-on or afterthought in policy decisions. That is particularly true during the pandemic.

Disabled people have paid a disproportionately high price throughout the pandemic. Multiple studies indicate that people with disabilities are more likely to die because of COVID. A report from the Canada Medical Association Journal suggests that of those patients admitted to hospital with COVID in Ontario in 2020, slightly more than 22 per cent had a disability. According to that study, those patients with a disability were more likely to die than those without (28.1 per cent versus 17.6 per cent). They also had longer hospital stays and higher readmissions.

Disabled Canadians ignored in policies on COVID-19

Prioritization and the risk of bias and discrimination against those with disabilities

Yet, the reporting of their deaths, when linked with their underlying conditions, diminished their passing in so many ways. When announcements were made that a disabled individual died of COVID, those who tried to downplay the pandemic as nothing worse than a flu pointed to those deaths as another example of Darwinism. It was fine if a disabled person died of this disease, they suggested. Somehow, our lives were worth less.

Many supports and services that disabled people required and relied upon during the pandemic were not deemed essential and were shut down – at a time when most Canadians could continue to shop at their favourite fabric store or browse their local big box grocer. For many disabled adults requiring regular access to medical care, the lack of available access to health-care services and increased wait times only made life more stressful. In addition, those who relied on the few day programs available had nowhere to go when COVID shut them down and other facilities couldn’t reopen because of lack of staffing and protective gear. Combine that with the loss of accessible public facilities such as libraries which provide free internet access, and you have an entire segment of Canadian society left waiting on the sidelines.

Provincial governments were slow in ensuring that disabled people living in personal care and long-term care homes weren’t being unnecessarily exposed to COVID, acting only after the fact in putting rules in place that prevented personal care workers from working in more than one facility at a time. Governments failed to ensure personal care workers had sufficient protective equipment while working in the homes of disabled people.

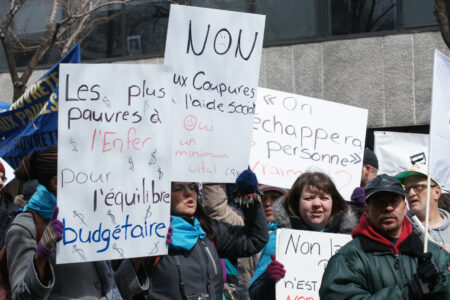

People with disabilities were already more likely to be living in poverty. Yet, we were among the last groups to receive a one-time pandemic financial assistance payment and that came only after intense lobbying on the part of disability groups. In June 2020, the federal government provided a one-time $600 payment for disabled people to pay for “extraordinary expenses incurred by persons living with disabilities.” By comparison, the government made available the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) months earlier, which paid out $2,000 a month, and ran the Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) was launched in May, worth $1,250 a month. Disabled people were an afterthought. The COVID adage that was supposed to unite us during the pandemic – “we’re all in this together” – served only to point out the inequities in the system for those of us who are disabled because we couldn’t be treated the same as everyone else.

Indeed, a Statistics Canada analysis noted the different effects of COVID on disabled individuals and employment. In a survey conducted between June 23 and July 6, 2020, about one-third of disabled participants indicated they had experienced a temporary or permanent job loss or reduced hours during the pandemic. About one-quarter of disabled people relied on disability benefits, while about 17 per cent received CERB or CESB. Almost one-third of participants reported that their household income decreased. Being able to feed themselves or provide PPE were the items most often cut from the budget. More than half had difficulty meeting a financial responsibility.

We must start exploring the realities of systemic ableism (discrimination on the basis of disability) no matter how distasteful that may seem. While society is gradually making headway addressing various forms of discrimination among marginalized groups, ableism is often not recognized or well-understood. Canada’s lack of policy and inattention to the issue of disability during a time when we were most at risk suggests it is time to start paying attention.

We are facing another wave. There will be another pandemic. We need to focus now on what that means to the lives of the millions of Canadians who are living with disabilities. For that we can look to the COVID-19 Disability Advisory Group Report for key recommendations. First, start by ensuring that all provinces collect and report accurate data (cases, recovered and deaths) disaggregated by disability, gender, race and other intersecting factors. Second, all levels of government must work on the protocols that ensure disabled people are given a priority in accessing health care that they require to function. Third, hospital visitation policies and essential worker categories need to be improved to ensure disabled persons are not made invisible once again. Finally, at the very least, all provinces must have an emergency response plan to support persons with disabilities when emergencies arise in the future.