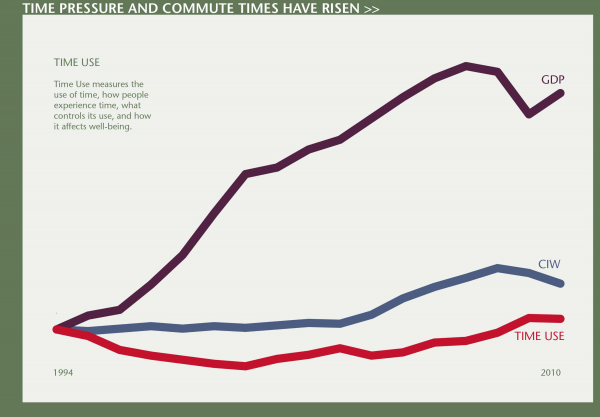

Over the coming decade or more, Canada’s potential economic growth will decline from above 3 percent annually a decade ago to below 2 percent annually. This is mostly because of demographic factors, but it is also because of Canada’s continuing poor productivity performance. Two percent growth has become the “new normal.”

There is currently a consensus that economic growth in Canada will fall below 2 percent in 2012 and 2013. Global economic prospects remain poor. The eurozone is in recession for the second year and is expected to remain depressed until 2014 or possibly beyond. Both the United Kingdom and Japan are in recession, for how long no one knows. It remains to be seen whether the United States has the political will to deal credibly with its fiscal and economic challenges.

The prospects in emerging market countries do not look very strong either. The International Monetary Fund is expecting that growth in the G20 emerging economies in 2013 will remain significantly below that in 2011.

This combination of weak global economic prospects and a lower “new normal” economic growth presents two major policy challenges for Ottawa. The first is to strengthen economic demand in the short and medium terms, and the second is to strengthen potential economic growth.

Meeting the first challenge would require the government to put aside its ideological commitment to eliminating the deficit by 2015-16. There is no fiscal crisis. There is not even a serious fiscal problem. The federal government’s most recent budget forecast put the deficit in 2015-16 at only 0.1 percent of GDP. The debt-to-GDP ratio is forecast to decline and, in the longer term, the fiscal structure is sustainable.

This leaves plenty of fiscal room for the government to extend its existing infrastructure program, which is scheduled to end in 2014. A 10-year program at $5 billion a year would raise the deficit to only 0.3 percent of GDP in 2015-16. The deficit would likely return to a surplus the following year. It would even be possible to double the size of the infrastructure program without long-term fiscal consequences.

The year of deficit elimination would be delayed, perhaps by one year, and Canada’s debt would rise. But the debt burden would fall, productivity would increase, jobs would be created and the unemployment rate would decline. Without action, the unemployment rate will remain stuck at above 7 percent.

Meeting the second growth challenge would be more difficult in political and policy terms, but it would pay off with a substantial increase in potential economic growth.

What is needed is a two-part tax strategy. The first part would simplify the tax system and the second would reform it.

Personal and corporate tax systems have become overly complex and inefficient. The current income tax system distorts market decisions, creates inefficiencies and reduces productivity and economic growth.

Simplifying taxes would pay off substantially in financial and economic terms, easily yielding savings of almost $6 billion annually. This could be reinvested in the economy to support economic growth through lower income taxes for all middle-income Canadians.

The second part of the tax strategy, reforming the tax system, would mean changing the tax mix so that it better supports investment, savings and labour force participation.

The generally accepted view among economists is that shifting the focus away from income-based taxation to consumption-based taxation could have significant benefits for economic growth. And there are other benefits that would result from a shift to consumption-based taxation. First, it would lead to greater revenue stability, as consumption fluctuates less than does income. Second, the cost of raising taxes through a consumption-based tax would be cheaper than through income-based taxes. Finally, a consumption-based tax would be more transparent.

The two-point reduction of the GST in 2006 and 2007 was one of the worst tax decisions ever taken — not just because of its adverse effects on economic growth, but also because it cost the government $14 billion annually in lost revenues. Doing so eliminated a surplus and created a structural deficit.

This decision should be reversed. The two points should be added back to the GST, and the $14 billion in additional GST revenues should be used to provide a significant reduction in personal income taxes. In other words, the change in the tax mix would be fiscally neutral and have no direct impact on the budget. In the longer term, however, it would strengthen economic growth and generate greater revenues.

To meet this two-part growth challenge would require a government unencumbered by ideology and willing to take political risks. Sadly, it is unlikely to happen, with the result that 2 percent annual growth is likely to become the ”new normal.”