Reputation has an unquestionable economic value to countries, just as it does to organizations and individual people. It is based on emotion and reason, the product of our impressions of a nation’s actions and its communications, as well as our deep-seated perceptions, stereotypes, influences and direct experiences. In an age of empowered, networked publics, the value of a country’s reputation is rising — as is the importance of managing it as one of its greatest assets.

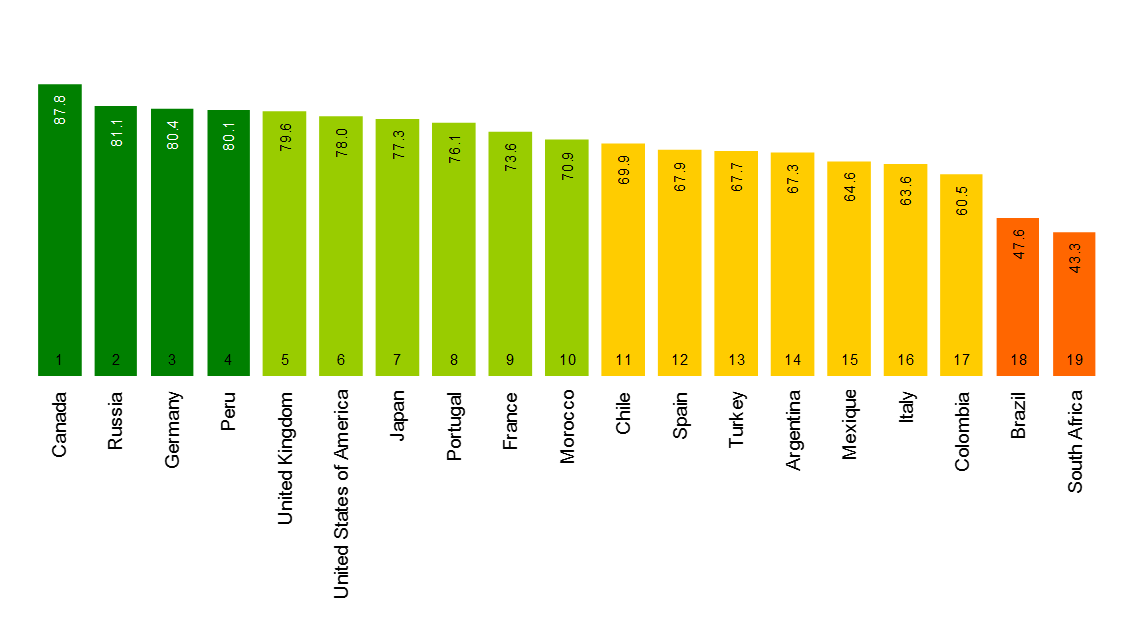

A new study of country reputations, released by the Reputation Institute and Argyle Public Relationships, suggests that Canada has this asset in spades, with a reputation that leads the world. The Country RepTrak survey included an online sample of 39,000 members of the general public from G8 countries, balanced to each country’s population based on age and gender, and also controlled by region. Respondents were asked to rate the reputations of the world’s 55 largest economies. The fieldwork for the study was conducted in March 2017. Here is a list of the top 20 countries, by reputation (figure 1).

The survey has implications for foreign policy, tourism marketing and international trade in many countries. A few findings stand out:

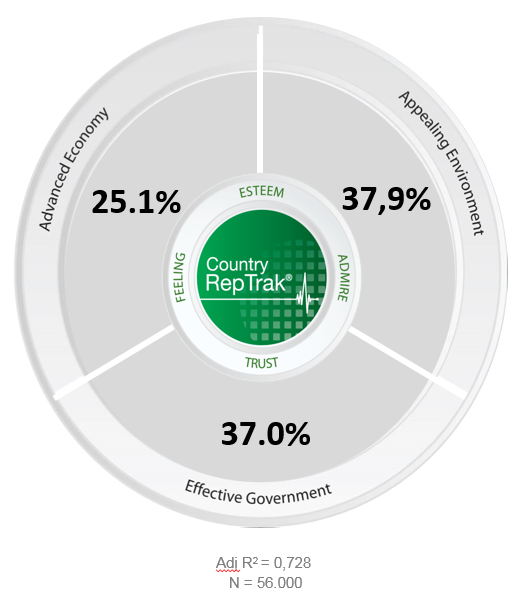

- Three factors drive national reputations: 37.9 percent comes from perceptions of its environment (e.g., welcoming people, beauty, lifestyle), 37 percent from its governance (e.g., public safety, ethics, international responsibility, social and economic policies), and 25.1 percent from its economy (e.g., educated and reliable workforce, contributions to global culture, high-quality products and services) (figure 2).

- The strongest national brands focus on all three reputation factors. Of the seven nations with “excellent” rankings (over 80 out of 100), Canada, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway and Finland are seen as global leaders in all three categories, while Australia’s and New Zealand’s reputations are powered by leadership in the environment and governance categories.

- Strong reputations create economic opportunities. Respondents who perceive a country as having a strong reputation state a greater willingness to visit it for business or leisure, or to recommend living in, working in, investing in, studying in, or buying products from, that country. For example, a one-point increase in a country’s reputation in a particular mark correlates with a 3.1 percent increase in visitors from that market, and a 1.7 percent increase in exports to that market over last year’s figures.

- Many emerging economies are gradually growing their global reputations. For example, while China still has a weak reputation, driven largely by poor governance, it rose in almost every dimension in the 2017 survey over previous years, with one notable exception — ethics. China’s most notable areas of rising strength are in perceptions of its technology, brands and business environment. If it can reduce corruption and be seen as a better global citizen, its reputational rise should accelerate.

- Reputation is both internal and external — and big gaps mean big blind spots. For example, Russia has the second-highest self-image in the world, with a rating of 81.1 from its own citizens, compared with one of the worst reputations (40.3) in the eyes of the rest of the world — a gap of 40.8 points. The US has the second-largest gap — its internal reputation is 78, which is 23.4 points above its external reputation. After last year’s fateful Brexit vote, the UK’s self-image rose, while its external image dropped, most dramatically in respondents’ openness to investing in the country. Since a strong country brand comes from countless actors — including institutions, businesses and ordinary citizens — the inability to be self-critical is a major risk.

Reversal in Canadians’ and Americans’ self-images

For most of the last century, Canada and the US have had very different self-images, with the northern nation perhaps lacking the self-confidence of its powerful southern neighbour.

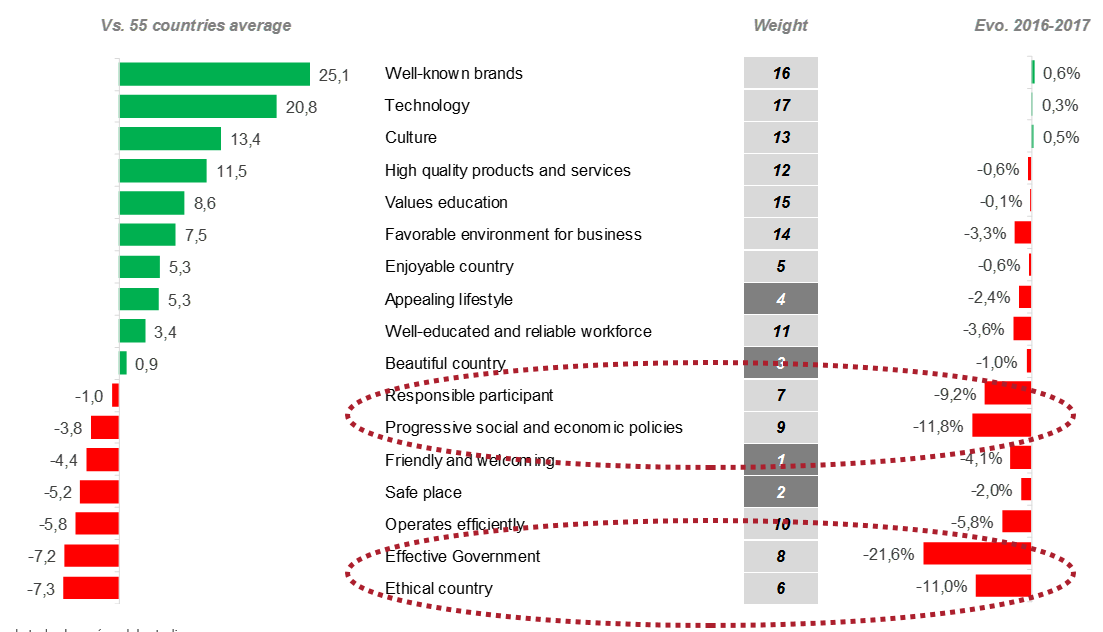

The 2017 study reveals an interesting evolution: we Canadians now have the highest self-image of any country in our assessment of our environment, governance and economy (figure 3). While Americans retain a healthy self-image — one that is well-earned in terms of the nation’s history and its renowned companies, products and brands — the rapid deterioration in its global reputation over the last year (the largest drop of any country in the world) should be cause for concern.

Fortunately for the US, respondents’ ratings of the country’s assets (brands, technology, culture, products and services) remain strong, even as perceptions of its governance have plunged. The need for international marketing of these assets has never been greater, as US industries and companies are likely to experience continued policy disruption and uncertainty about their future access to foreign markets (Figure 4).

The context behind last year’s US presidential election was an internal debate about the nation’s greatness: whether its global status was rising or falling, and whether America’s economic self-interest would be best served by globalization and engaged multilateralism or nativism, protectionism and unilateralism.

While this debate continues in America, the Reputation Institute study suggests that great nations are those seen as great global citizens. Being a “responsible participant in the global community” was one of the top drivers of perceptions of that country’s government in the survey. And in a multi-polar world in which talent is more mobile than ever, building a strong economy is much easier if you have a strong reputation, as citizens and consumers of other countries are more likely to become your visitors and customers.

Implications for Canadian leaders

For Canadian leaders, the survey highlights several opportunities.

- Use Canada’s excellent reputation as a strategic asset to be managed and measured. There is a particularly compelling opportunity to highlight the nation’s overall reputation in marketing the country as a business destination — the one area of reputation in which Canada consistently rates slightly lower than the other most reputable nations.

- Be assertive in our commitment to multilateralism and free trade. Canada’s strong internal reputation suggests that the self-conscious, defensive and often brittle nationalism of our past is largely behind us. This internal confidence should strengthen our hand in pending negotiations with the US and other trade partners, and being a strong voice in multilateral global forums such as the G-20.

- Avoid complacency and triumphalism. Differentiating Canada more aggressively from the global competition remains a priority, as does maintaining a capacity for healthy self-reflection, particularly about tangible actions we can take to foster innovation, enhance productivity, and ensure a more competitive environment for business.

- Intergovernmental and multi-stakeholder collaboration: In terms of local, provincial and regional markets, there is an excellent opportunity to leverage the strong reputation of the national brand and collaborate more closely in business and tourism marketing.

As the global business and trade landscape becomes more competitive, investments in building strong country reputations will continue to deliver substantial economic value. Building a reputation is not something that governments can do alone, nor is it just about marketing — the key is tangible action, conducted in partnership, and backed by both local and global communication.

Photo: People wearing Canadian flags watch fireworks explode over the Peace Tower during the evening ceremonies of Canada’s 150th anniversary of Confederation, in Ottawa on Saturday, July 1, 2017. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.