Every prime minister since Sir John A. Macdonald soon appreciates that there are three files that require his or her personal and continuing attention. The first is preserving national unity. The second is protecting national security. The third is managing the relationship with the United States.

A plank in the victorious 2006 Conservative campaign was the promise to improve the relationship with the US; it had become increasingly frosty during the latter days of the Martin government. Looking back over the past six years, the Harper government has delivered on that promise.

Stephen Harper has demonstrated the ability to get along with first a Republican and now a Democrat in the White House. He has taken to heart Brian Mulroney’s admonition that development of a rapport with the occupant of the Oval Office is the most important personal relationship for any prime minister.

It is not the bonhomie that characterized the relationship of Mulroney with Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush nor the “golf buddy” camaraderie of Bill Clinton and Jean Chrétien. But with both George W. Bush and Barack Obama, Harper has achieved professional respect and, importantly, trust as a reliable ally.

There have been differences. George W. Bush was baffled by Harper’s unwillingness to join ballistic missile defence (thus sticking with the Martin government’s rejection). Obama and Harper take different approaches to government, but this has not prevented cooperation on most of the big files with a couple of exceptions: Harper’s unyielding philo-Semitism and skepticism on climate change.

The Harper approach has been characterized by no drama and little recrimination. He has followed the Mulroney dictum “that we can disagree without being disagreeable” and its important corollary that we usually achieve more when we start with the “big table” international issues.

Importantly, Harper has also realized that if we are to achieve results it is incumbent on him to take the initiative and then personally intervene to ensure it succeeds. This is nowhere better illustrated than with the announcement in December 2011 of a framework agreement on the border and perimeter security. It was his “ask” of both Bush and Obama. When it became clear that the only progress on Obama’s promise of border action at the Ottawa summit in February 2009 would be about enhancing security rather than expediting access, Harper got Obama to re-ignite the process at the Toronto G20 summit of June 2010. He journeyed to Washington in February 2011 to start the formal negotiations and then returned in December to announce the framework agreement.

From the outset, Harper has made the economy the central theme of his government. Trade is critical to our prosperity and, notwithstanding the current malaise, the United States will always be our main market. About half of what we produce is destined for what is still the world’s biggest market.

To put it another way — we export more to Michigan in nine months than to China in a year. Most of what crosses over the Ambassador Bridge or through the tunnel between Windsor and Detroit is auto parts.

The auto bailout story is as remarkable as the original Auto Pact. The Prime Minister and the President closed the auto deal in what is a defining moment of their partnership. Accomplished quickly in the spring of 2009, with minimal fuss, it involved three levels of governments, unions and management on both sides of the border.

While energy exports have eclipsed the auto trade in value, the auto industry is still our biggest manufacturer. It is also the most integrated industry in the Canada-US supply chain dynamic. Its recovery is a notable success, as President Obama is now reminding American voters.

The auto story also illustrates another dimension of the Harper government. With rare exception (i.e., Israel) it is less about high principle than pragmatism. Incrementalism that gets the job done characterizes much of the Harper approach to policy development and delivery. In recognizing a role for government intervention, Harper differs from the current GOP presidential contenders who continue to trumpet their opposition to anything resembling “government bailout,” including that given to GM and Chrysler.

Stephen Harper has demonstrated the ability to get along with both a Republican and a Democrat in the White House. He has taken to heart Brian Mulroney’s admonition that development of a rapport with the occupant of the Oval Office is the most important personal relationship for any prime minister.

The security relationship has always been paramount in American eyes. Mindful of the irrestible dictates of geography, Franklin Roosevelt included us in the American defence umbrella. Our defence alliance remains rooted in the still vital Permanent Joint Board of Defence (1940) and, since 1958, the North American Air Defence Agreement.

Afghanistan and Libya have re-established our credentials as a nation that knows how to fight, a Canadian credential during our first century, which then declined into the torpor and false comfort of peacekeeping. We ran down our Armed Forces and defence commitments in what former chief of defence staff Rick Hillier would describe as a “decade of darkness.”

Americans would accuse us, with some justice, of freeloading. Successive American ambassadors, Democrat and Republican, were more polite in their language but they made it clear that that we needed to invest more and pay more attention to security. Former US ambassador Gordon Giffin put it bluntly: “Canadians feel some entitlement to unfettered access to US markets and military clout. That’s implicit in the lack of military spending here. We’re not telling you that you have to do this or that, we’re saying that if you want the access you expect, this is what you need to do.” His successor as US ambassador, former Massachusetts governor Paul Cellucci, was explicit in encouraging Canada to develop a “lift” capacity.

Re-armament began during the Martin government. Harper’s “Canada First Defence Strategy” is as described, as long as the funding to sustain the next generation of fighter jets, warships and the kit to sustain the army’s expeditionary capacity is appropriated and delivered on schedule.

The biggest differences with the Obama administration are on climate change and energy. Even here, the “agree to disagree” is mostly without histrionics although government comments about “foreign funding” — Tides Foundation support for environmentalism — was juvenile. Instead of being a laggard on carbon containment, we should be a leader, as Mulroney demonstrated with his “Clean Hands” approach on acid rain. Fortunately, the differences on Kyoto and the Copenhagen conference debacle did not interfere with then ongoing, critical talks on global economic recovery. Nor has the presidential decision to reject, for now, the Keystone XL pipeline interrupted the important practical implementation of the border and regulatory accords. The XL pipeline may be a “no-brainer” but rather than harp on it, Harper parlayed the rejection into a personal invitation into the TransPacific Partnership from President Obama at the Honolulu APEC Summit. In a sense, he knew Obama owed him one and played the card skillfully. Meanwhile, Harper has built on his own pivot toward China and made construction of a pipeline to the Pacific, specifically the Northern Gateway Pipeline, a priority. When you only have one buyer, and that buyer proves unreliable, opening a second market is both good policy and, mindful of his base in Alberta, good politics.

Bashing Uncle Sam is part of our DNA, a recessive gene inherited from the United Empire Loyalists. It has become obligatory for every prime minister, at one point or another, to tweak the beak of the eagle as a demonstration of their nationalism. It is a time-honoured tradition in Canadian politics dating back to Sir John A.’s electoral hurrah of “the Old Flag, the Old Policy, the Old Leader.” Brian Mulroney couldn’t be bothered and, despite bringing home the FTA/NAFTA and Acid Rain Accord and advancing American acknowledgement of our sovereignty in the Arctic, paid a price in loss of public confidence.

Shortly after his first election victory, Harper used some innocuous, if ill-timed, remarks by US ambassador David Wilkins to deliver a passionate defence of Canadian sovereignty in the North. It established his nationalist bona fides. To his credit this was not mere chest-thumping but a declaration of major policy and Harper has personally visited the Arctic every summer in tandem with what are now regular exercises by the Canadian Forces.

It is right for Canadian trade ministers to weigh in on the inequities of “Buy America,” if only to remind our American partners that disruption of our supply chains is a self-inflicted injury and a sure-fire way to encourage “outsourcing” abroad. However, there needs to be some serious threat analysis before we tub-thump.

Making laws in Congress is truly like making sausage and most of what goes into Congress, including legislation proposed by the president, comes out quite differently, if at all.

We also need to calibrate our response, especially with regard to inflammatory ministerial statements that garner headlines at home but do nothing to advance our interests in Washington.

Better to rely on the advice of our respective ambassadors. Good ambassadors are like good quarterbacks. They take the play from the coach but then adjust it to circumstances on the field.

Harper has been well served by Michael Wilson and, now, Gary Doer. Wilson, who directed the NAFTA negotiations as trade minister in the second Mulroney government, successfully put to bed the softwood lumber deal (an accord that continues) and NORAD renewal. He also managed the controversy during the 2008 primaries over the leak of a diplomatic cable reporting on a conversation with then Obama adviser Austan Goolsbee (who later become chair of President Obama’s Economic Advisory Council).

Gary Doer has been preoccupied with energy, especially the oil sands and the XL pipeline, and he has taken environmental critics to task for using outdated facts, what he calls “frozen facts” on water use; for example, facts that fail to acknowledge industry innovation. As a former Manitoba premier, he also has an understanding of transboundary water issues and innately understands the importance of the states in the US system.

We have been similarly well-served during the Harper years by both US ambassadors. David Wilkins, the former South Carolina House speaker and lawyer, served during the second Bush administration and his Southern charm and humour did much to mitigate the unpopularity of his president among Canadians.

David Jacobson, the Chicago lawyer who served in the Obama White House, has had an easier time of it. Canadians like Obama, apparently much more than do Americans. Like his counterpart in Washington, Jacobson is a doer, who hasn’t hesitated to pick up the telephone and sort out the problem with agency heads in Washington (a benefit of his delayed arrival to Canada was that, from his post in the White House appointments office, he got to know most of the senior Administration).

Together, Jacobson and Doer have stick-handled potential problems and their personal intervention and contacts were vital in ensuring successful implementation of the 2010 Procurement Reciprocity Agreement. Jacobson worked the inter-agency heads, while Doer, the one-time labour negotiator, worked the unions. Doer is the second former premier (New Brunswick’s Frank McKenna served under Paul Martin) to be “our man” at our splendid embassy on Pennsylvania Avenue.

With regard to political leadership, premiers, next to the prime minister, probably best understand the importance of the US relationship. The sea change in provincial attitudes toward closer economic relations with the US is the most notable development in Canada-US relations. The provinces were deeply divided over the free trade agreement but its success has made every premier, regardless of party, appreciative of the US market. The economic weight of American states remains impressive. Today, there is virtual unanimity among premiers about the value of an activist approach, covering the broad range of shared interests, to their gubernatorial counterparts. There is also recognition of the need to “work” these personal relationships. It was the premiers’ consensus, at the Council of the Federation, to mostly open up their procurement market that made possible the Procurement Reciprocity initiative. Their intervention with their governor counterparts was essential to heading off potential congressional opposition.

The United States will always be our main market. About half of what we produce is destined for what is still the world’s biggest market. To put it another way — we export more to Michigan in nine months than to China in a year. Most of what crosses over the Ambassador Bridge or through the tunnel between Windsor and Detroit is auto parts.

Congress deserves more attention. Under Allan Gotlieb, the Canadian embassy radically changed its approach to congressional relations in the recognition that while the administration is our entrée to Washington, the battlefield is the Congress and that we could not depend on the administration to deliver for us on Capitol Hill. Interparliamentary relationships are particularly strong at the state and province level and Canadian legislators regularly participate in the National Conference of State Legislators and their regional affiliates as well as the Council of State Governments.

The most successful cross-border association is the Pacific NorthWest Economic Region (PNWER) with its exceptionally talented secretariat based in Seattle. They picked up the ball on the “smart driver’s licence” initiative, the clever compromise over the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative requirement for Americans to show a passport when re-entering the United States. It would have curtailed Americans living in the Pacific northwest who wanted to drive up to Vancouver for a couple of days at the 2010 Winter Olympics. By working state legislators and their congressional delegation, PNWER helped achieve recognition of the licence by the US Department of Homeland Security.

Three elections and six years on, Prime Minister Harper will be thinking inevitably of legacy and what remains to be done.

His first goal must be economic, beginning with the effective implementation of border access and regulatory reform. Negotiations produced a blueprint with a series of pilot programs designed to improve border infrastructure, expedite the passage of people and goods and eliminate red tape and standards that impose a “tyranny of small differences” on trade.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership has the potential to open up new markets while giving us the opportunity to rid ourselves of the costly burden of supply management. The initiative should also provide the cover to effectively update NAFTA, with trilateral attention to our supply chains. This should include a look at the arteries of our highways, air and waterways, and our gateways of ports, airports and border crossings.

Opening doors across the sea is important but so is efficient continental production. We should develop a continental appreciation of our labour market and link it to education and accreditation. We need to ensure easier cross-border access, especially for business.

A look at the White House readouts of calls between the two leaders reveals that Harper has also mastered yet another Mulroney instruction: start on the big table of global geopolitics before getting to the “condominium” issues, as former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice once referred to what is often literally the meat and potatoes of our relationship. Bearing the burden of global primacy, presidents are always interested in what others can bring to the discussion.

Three elections and six years on, Prime Minister Harper will be thinking inevitably of legacy and what remains to be done.

At his first meeting with George W. Bush, at the trilateral North American summit in Cancun, Harper was surprised by Bush’s personal and erudite tour d’horizon of the international scene and its players. Harper got the message — big table international politics is always top of mind for American leaders. Even at the December 2011 meeting to announce the border accord, Harper’s discussion with Obama focused not on the accord, but on the international crisis spots.

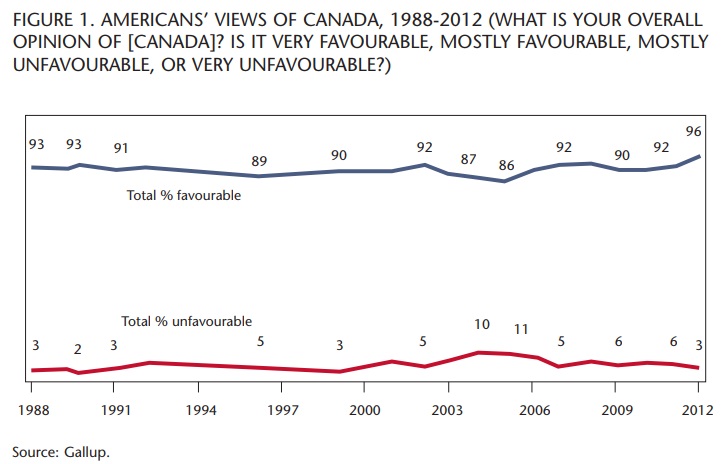

With interest and experience, Canadian prime ministers can play on global developments. As Gallup has shown (figure 1), Americans like Canadians, partly because they think we are mostly the same. Personal chemistry at the top obviously counts but we start with the benefit of common language and an appreciation of American culture. Sports and entertainment is a solid base to move into geopolitics.

Our perspective is appreciated, if not always welcomed. Pierre Trudeau’s peace initiative got short shrift in Ronald Reagan’s Washington, but there was keen interest in what he picked up on his odyssey and grudging respect for his intellect. Mulroney was welcome even when he took a different approach on South Africa than Reagan (and Margaret Thatcher). He and Joe Clark later played a helpful fixer role in the unification of the Germanies.

Two debilitating foreign wars, a global recession that has shaken Americans’ sense of well-being, the rise of China as a rival superpower, and once more there is talk of American decline and waning influence. While the challenges are real, declinism is a recurrent theme for the chattering classes and the academy. It is punctuated in its latest manifestation by the gridlock of its government that goes way beyond the checks and balances between the executive and legislature that was part of the Founding Fathers’ design. One result is popular contempt for whatever party is in power and a resultant discontent that finds voice through the Occupy Wall Street movement on the left and the Tea Party on the right.

But in the rush to embrace a post-American world, if there is a recurrent theme in the American experience, it is that it would be a mistake to bet against American resiliency and the remarkable capacity of the US for reinvention.

We should not forget that the liberal international order that has served the Canadian interest is underpinned by American power. If not the “indispensable” power, then the US continues to be the default power, even when it leads from behind. An American retreat would have a calamitous effect on Canadian interests. A core and continuing Canadian objective in the making and maintenance of the architecture and institutions that have served us since the Second World War has been to find ways to sustain American engagement.

Looking forward, there are a number of initiatives that would benefit from Harper’s personal attention. They would serve Canadian interests as well as support the United States as it continues to bear the burden of global primacy.

The first is the global economic situation where Harper initially established his rapport with Obama in the almost monthly merry-go-round of international summits during 2009. Harper has championed pragmatic fiscal discipline while Finance Minister Jim Flaherty and Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney have developed a Canadian perspective on both fiscal and monetary issues. Carney’s contribution has been recognized in his chairmanship of the Financial Stability Board. Whoever is American president in 2013, jobs will continue to be top of the agenda. Obama has pledged to double American exports. We are already America’s main export market, a fact not generally recognized in Washington, but an obvious advantage as we implement the border and regulatory accord.

The US has served notice that allies will have to do more as it comes to terms with its debt. The US Navy, the guarantor of safe passage on the Seven Seas, will shrink at a time when 80 percent of world commerce travels by sea. Meanwhile, we are negotiating trade deals that depend on the security of sea lanes. We have the longest coastline in the world — enough to circle the equator six times, and Harper has made sovereignty and stewardship in the Arctic and northern passage a personal priority. As future chair, we have an opportunity to make progress diplomatically within the Arctic Council, where we usually find common cause with the US. More importantly, there can be no backpedalling on our commitments to the Royal Canadian Navy and the procurement of our new icebreakers and supply and combat ships.

One of the best initiatives of the Harper government has been the Halifax International Security Forum, which annually brings together the transatlantic national security establishment. This fine idea should be replicated on the West Coast, as the gateway to more and more of our trade. A pipeline will be of little use if there is turmoil in the North Pacific.

We have common interests in the Americas, something that the US has recognized since President James Monroe declared the continent to be within its sphere of influence. While we were late in embracing our continental identity, Harper has promised to be “ambitious” and declared the Americas a priority. Canadian business, notably our banks and mining companies, have found their niche. Boutique trade agreements are useful but we should do more.

While the overture to Brazil is welcome, we should focus on Mexico, our NAFTA partner. The existential drug war will be on the plate of whoever succeeds President Felipe Calderon later this year. The Americans have encouraged us to help in training Mexico’s judiciary and police and continuing to work with the US in drug interdiction on land and sea.

Nuclear proliferation has kept every American president since Harry Truman awake at night. The recent Seoul summit follows on the 2010 Washington summit hosted by President Obama, and against the backdrop of new sanctions as Iran moves toward bomb-making capacity.

While the Fukushima experience is a setback, nuclear power is going to be part of the global energy solution. The challenge is what to do with the spent fuel and its by-product plutonium — the vital ingredient in making nuclear bombs. Canada is a uranium superpower. Mines in northern Saskatchewan provide nearly a quarter of world production. After the Toronto G20 summit, Harper and Obama announced an entente to further secure inventories of spent highly enriched uranium. We should declare permanent stewardship of Canadian-mined uranium and its by-products.

We should also invite the other uranium producers — Australia is the next biggest producer — to follow suit. International solidarity among the producer states would effectively close the proliferation loop.

Former US senior cabinet secretaries George Shultz, William Perry and Henry Kissinger and former senator Sam Nunn have collaborated on useful steps to reduce and ultimately eliminate nuclear proliferation and nuclear weapons. Philip Taubman chronicles their efforts in a new book, The Partnership: Five Cold Warriors and Their Quest to Ban the Bomb. It concludes with this observation from Henry Kissinger: “Once nuclear weapons are used we will be driven to take global measures to prevent it. Some of us have said, ‘Let’s ask ourselves, if we have to do it afterwards, why don’t we do it now?’“

These initiatives serve our national interest as well as contribute to the big-table issues of peace and security, the issues with which every American president starts his day.

Stephen Harper is now a senior Western leader with place and standing on the international circuit. He has achieved the trust and confidence of both George W. Bush and Barack Obama. Differences, notably with the Obama administration on climate change, have been managed without rancour or drama. The transactional disputes — perennials like lumber and, more recently the Keystone XL pipeline — have been left, appropriately, to our competent ambassadors and ministers.

On our most important issue — expediting trade at a border that had thickened — Stephen Harper demonstrated the qualities that Canadian prime ministers must develop if they are to advance our interests with the United States: persistence and perseverance.

A sense of timing is also important, and Harper seized on Obama’s pledge to create new jobs through trade. Harper is helped by the fact that Canadian anti-Americanism is at a low ebb, in part because we like President Obama. There are still chapters to write on the Harper relationship with the United States. We need to see evidence of improved access at the border. But the foundation is solid and there is a record of sound, successful management and opportunities for further achievement.

Photo: Shutterstock