The Liberal government promised a diversity and inclusion agenda, and made specific commitments to ensure more inclusive representation in appointments. A year later, how well have they implemented this commitment?

There is gender parity in cabinet, but just over one-third of parliamentary secretaries are women. The representation of visible minorities in cabinet (17 percent) and among parliamentary secretaries (24 percent) is stronger than their proportion of the population (15 percent of those who are Canadian citizens). There is also stronger representation of Indigenous persons, with 2 in cabinet (later falling to one following the resignation of Hunter Tootoo), and 1 parliamentary secretary.

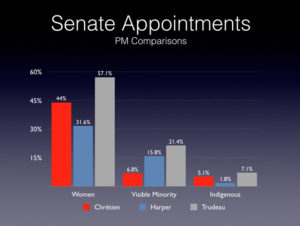

Similarly, the 28 Senate appointments emphasized diversity: 16 women (57 percent), 6 visible minorities (21 percent) and 2 Indigenous persons (7 percent). Figure 1 contrasts the diversity of Senate appointments of Prime Ministers Chrétien, Harper and Trudeau.

FIGURE 1

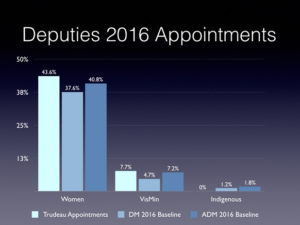

In contrast, the appointments of the most senior public servants (39 deputy ministers and associate ministers) are less representative of diversity than at the political level: 17 women (44 percent), 3 visible minorities (8 percent) and no identifiable Indigenous persons. However, as shown in figure 2, this shows more diversity than the pre-Trudeau government baseline, although not with respect to Indigenous persons.

FIGURE 2

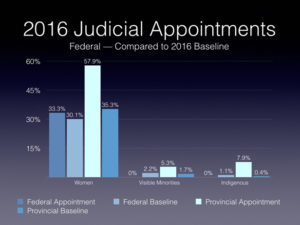

Of the 41 judicial appointments made by the Trudeau government, 23 were women (56 percent), with two visible minorities (5 percent) and three Indigenous appointments (7 percent). Figure 3 contrasts 2016 appointments with the baseline, separated out by appointments to federal courts and federal appointees to provincial courts.

FIGURE 3

The three appointments to the federal courts, including the Supreme Court of Canada appointment, included 1 woman but no visible minorities or Indigenous persons. However, federal appointments to the provincial courts reflect the increased diversity of appointments: 58 percent women, 5 percent visible minority, and 8 percent Indigenous people.

With respect to the 9 appointments to the federal and provincial supreme courts, 4 were women and 1 was an Indigenous person.

Given the nature of the Privy Council Office’s Governor in Council appointment index, it is not possible, in a timely manner, to assess the diversity of appointments outside the deputy minister and judicial realms.

In April, the Ottawa Citizen’s columnist Andrew Cohen wrote “Justin Trudeau has told Global Affairs that its list of career candidates [for Head of Mission, or HoM appointments] has too many white males and asked it to do better next time.” Some six months later we can judge how well Global Affairs Canada responded to the PM’s direction, given that most if not all ambassadors and consul general appointments were made as part of the customary summer rotation in the foreign service. Moreover, as we have a complete list of their position classification levels, we can compare the diversity with respect to more senior and junior positions.

Overall, of the 45 appointments, 21 were women (47 percent, virtual parity) and 5 were visible minority (11 percent, under-represented in comparison with their proportion in the general population( 15 percent of those who are also citizens). Two of the visible minority appointments were women, 3 men. No identifiable appointments of Indigenous persons were made.

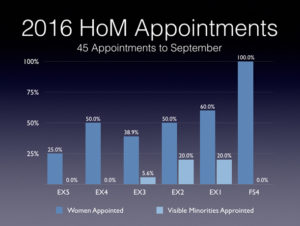

Figure 4 breaks down these overall numbers by classification level. The classification level of the individual head of mission (i.e., EX5, EX4) may be either greater or lower than the position level they hold, but the latter provides a more consistent basis to assess these appointments (as well as avoiding privacy issues).

FIGURE 4

Not surprisingly, there is greater representation of women and visible minorities in appointments at more junior levels, particularly apparent between EX4-5 (assistant deputy minister level) and EX1-3 (director general and director level), as shown in figure 5 (two-thirds of HoM positions are classified at the EX2-3 level). This suggests that over time, women and visible minority representation at more senior levels will increase.

FIGURE 5

So, what does this mean in terms of the overall commitment to great diversity among appointments? The evidence to date indicates that the government is largely delivering on its commitment with respect to women and visible minorities but less so with respect to Indigenous persons.

The real test will occur with respect to Governor in Council appointments, given that these attract less public attention and happen largely below the radar. Given the government’s track record to date, it is likely that representation will improve, but the government needs to ensure that, at a minimum, its index of appointments allows easy tracking and, ideally, an annual public diversity report.

However, almost one year in, this appears to be one commitment met.

Note: I am grateful to Global Affairs Canada for having provided the classification data. However, as an illustration of the limits of the newer, more open approach, they did not provide this information in spreadsheet form, using the (false) argument that: « Understandably, the GoC cannot send records in a spreadsheet format that could otherwise be manipulated or ‘edited.’ » (Fortunately, I have software that can convert a scanned pdf into spreadsheets or documents). I am also grateful to the Privy Council Office for providing some of their internal tracking documents, which have 25-year data with respect to women, in spreadsheet form.

Photo: Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.