The recent and very public debate about retirement safety in Canada is replete with alarming statistics. In particular, reports quoted by all sides in the discussion suggest that only about one-third of Canadians currently belong to a formal pension plan. What does that mean? Well, the common understanding is that if you participate in a pension plan, at your departure from the workplace, your “work paycheque” will seamlessly convert to a “retirement paycheque” for life. The unspoken implication, of course, is that the other two-thirds of Canadians are “up a creek” — in contrast to the lucky third of pension participants; they’ll be living on cat food in retirement, counting every penny as the days go by and constantly fretting about outliving their savings (or if they aren’t worried, they should be!).

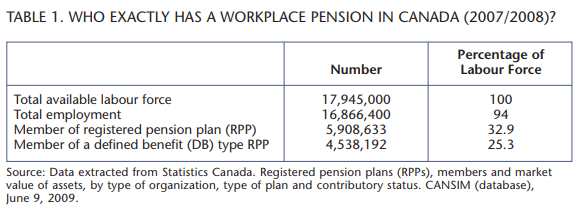

At first glance, the available data seem to support this rather bleak picture. According to no less an authority than Statistics Canada’s 2008 Canada Year Book, 32.5 percent of the Canadian labour force was covered by a registered pension plan during the year 2005. This is the most recent year for which numbers are available, and it is thus now five years out of date. But back in 1985, the relevant proportion was 35.3 percent, which indicates a decline of almost three percentage points over 20 years. Looking at the numbers more closely, you can see that this national average masks a discrepancy across the genders. For men, pension coverage has dropped almost 10 full percentage points over the last 20 years — from 39.9 percent (1985) to 31.9 percent (2005) — while for women it has actually increased (but not as much), from 29.0 percent (1985) to 33.3 percent (2005).

So yes, it is clear that the majority of working Canadians — about 67 percent of the workforce — are currently pensionless. Ergo, it is no surprise that the public policy question du jour is what to do about those people who for whatever reason aren’t fortunate enough — or savvy enough — to participate in a registered pension plan. Surely, conventional wisdom suggests, these are the Canadians most at risk of inadequate retirement savings. Proposals abound…and much ink has been spilled. Here are some of the issues being debated. Do we increase the Canada Pension Plan from its current maximum benefit of $10,600 per year? Do we allow for greater tax-sheltered savings? Do we mandate universal pensions for all employees? Again, the assumption underlying all of these discussions is that the population about whom we should be most concerned is the 67 percent majority of Canadians, who do not belong to a registered pension plan.

But allow us to be contrarians for a moment. We are actually quite concerned for a large fraction of the so-called “lucky third” — those who think they will retire to a guaranteed pension income, when in fact they have nothing of the sort.

To understand our concern, let’s first take a look at developments across the pension landscape over the last few decades. A quarter of a century ago, when the people who are thinking now about retirement in the next decade likely started their work lives, the vast majority of the largest and most prestigious employers in North America offered defined benefit (DB) pensions to their employees. This form of pension promises a lifetime of income to each retiree, when he or she stops working, with potentially a survivor pension for your spouse after you die, too.

However, over the last few decades, the proportion of companies offering DB pensions to new employees has dropped to less than 20 percent of large employers. The remaining 80 percent of companies that still offer pensions have switched to what are called defined contribution (DC) plans. DC pensions are still considered “registered pension plans” for Statistics Canada purposes — even though they are essentially tax-sheltered investment plans with zero guarantees…and no promises. In DC (a.k.a. money purchase) pension plans, money flows into the pension plan pot, it gets invested by professional (hopefully) portfolio managers in the volatile stock and bond market, and the gains are tax-deferred until such time as the income is received — but nowhere is anything mentioned about a guarantee.

Do we increase the Canada Pension Plan from its current maximum benefit of $10,600 per year? Do we allow for greater tax-sheltered savings? Do we mandate universal pensions for all employees? The assumption underlying all of these discussions is that the population about whom we should be most concerned is the 67 percent majority of Canadians, who do not belong to a registered pension plan.

But the meaning of a pension to a financial economist or a financial planner is very different from the popular understanding among members of the general public, or to a human resource specialist, a labour lawyer, a populist politician or even a consumer agitator. We strongly suspect that the current discussion of the “pension crisis” in Canada glosses over the vital distinction between DB and DC pensions, and this is the source of our concern. The situation today is that many people who think they have a pension really are members of a collective saving and investment plan. Worse still, because workers in this fragment believe they are in the lucky cohort, we suspect they are relating to their DC pension entitlements more like DB entitlements, and they won’t wake up to the difference until it’s too late. More importantly, getting the 67 percent of pensionless Canadians into a tax-sheltered savings plan won’t solve their retirement income problems.

So, in discussions of the current pension crisis, let’s be perfectly clear about what we mean by “pension.” A pension is not a synonym for a large sum of money, a diversified asset allocation or a retirement residence in Florida. In our view, even a seven-figure RRSP is not a pension.

Instead, a pension involves a binding contract. A pension includes a guarantee. A pension is a pledge that you — the retiree — will receive a real, predictable and reliable income stream for the rest of your natural life. A pension is more than an asset class; it is a product class.

A true pension also involves more than just you. A true pension tango requires two parties: you, the prospective retiree, and your dance partner, the entity standing behind the promise. The counterparty to the pension promise can be an insurance company, government entity or corporate pension plan. But for it to be called an honest pension there must be somebody guaranteeing something. No guarantee? No pension.

But why is a guarantee so important? We work in the field of retirement income modelling and planning, and we spend a substantial portion of our professional time computing what is known as the “probability of ruin” for specific retirement income plans. Our quantitative analysis indicates that you might have 20, 30 or even 50 times your annual needs in liquid cash at retirement — sitting in the most diversified of mutual funds or investments and RRSPs — and yet you still run the risk that your portfolio will not last as long as you do. Such is the nature of random and unpredictable human longevity combined with financial volatility. Indeed, future breakthroughs in medical science, unexpected inflation or another miserable decade in the stock market individually or collectively can generate a nontrivial lifetime ruin probability for even the wealthiest of retirees. Guaranteed lifetime income greatly reduces this probability for retirees. Non-”pensionized” assets do not.

As we’ve said, if you have a guaranteed lifetime pension, your pension dance partner will continue to send your monthly cheques, come economic hell or financial high water. Note that this is no trivial promise to make. Indeed, many corporations — from Nortel Networks to United Airlines — have defaulted or are in the process of weaseling out of this simple contract. Others have given their aging pensioners undesirable financial haircuts by reducing their expected monthly income ex post facto.

In the last decades, companies have walked away from pension obligations and dumped the problem on governments and the public. Indeed, a true pension is as rare as it is expensive. We’ll even go so far as to say that even the promise of a gold-plated corporate DB pension that pays 100 percent of preretirement salary, inflation-adjusted, for the rest of the retiree’s life, is not a pension if the company can renege on the promise by filing for bankruptcy.

So now that we’ve provided a sense of the value of a pension, let’s talk about the cost. To get an idea of what a true guaranteed pension will set you back these days, consider the following example. Imagine you are a 62-year-old contemplating early retirement. You ask your favourite A-rated insurance company agents to “quote you a pension.” They will likely offer something in the following price range: for every $10,000 of guaranteed, inflation-adjusted annual income you would like to receive for the rest of your life, you must give us $180,000 upfront. Yes, you read that correctly: you need to ante up with 18 times the desired annual income. So let’s do the math: if you want $55,500 of inflation-protected annual income for the rest of your life, that’ll cost you a cool million. No, this is no Madoff-like scheme to make off with your RRSP.

This is the fair price in the open market for a life annuity, which is the closest thing to a DB pension that exists in the retail market. If this type of retirement income seems too expensive, the market price is telling you something.

Now, you might think, “Heck, I have $1,000,000 in my RRSP and I can invest it myself to create my own $55,500 pension.” Well, here is our warning to you: there is no risk-free lunch. There is a very good reason the insurance company charges you what seems to be so much. First, interest rates are abnormally low right now, which increases the cost of any guarantee. But secondly, and more importantly, by offering you a lifetime income stream, they are taking the longevity risk off your personal balance sheet — and placing it on their corporate balance sheet. Generating $55,500 per year might not seem like much if you have a million to spare, but if you have that viewpoint, you are probably falling victim to behavioural biases. In other words, you are fooling yourself — and it’s time to nudge you back to reality. Pensions are expensive because they are valuable, even if you don’t think so.

In fact, according to something called the lifecycle model (LCM) — which is a marvellous tool employed by economists to gauge optimal consumer demand for consumption, savings and investing from cradle to grave — the true value of a true pension is astonishingly high. Think of the LCM like a bathroom scale. You can use the scale to measure the weight of any item, even if you can’t weigh it directly. For example, if you stand on the bathroom scale fully clothed, and then do the same totally naked, you can calculate the weight of your clothes even if you never put them directly on the scale.

The LCM can be used in this way to measure the “utility value” of a pension for individuals with pensions and those without. To make a long and complex mathematical story short, the utility value of a pension can be worth up to half of your typical net worth. One implication of this finding is that a rational retiree (risk-averse, healthy and pensionless) would rather have $500,000 worth of pension than $1,000,000 worth of cash. Yup. You read that one correctly as well. The message from this model is that most Canadians would be willing to pay — keeping in mind that “willingness to pay” is a fundamental concept in economics — a large premium to exchange their cash for pensions. (This insight was actually first derived and recognized by Professor Menahem Yarri, the current president of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humaniies, almost 50 years ago in his PhD dissertation at Stanford University.)

In fact, while on a historical note, when back in 1881 the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck gave his historic speech to the German Reichstag in which he introduced what we now know as the first old age pension, to be paid by the state to all its elderly citizens, he didn’t introduce a tax-sheltered savings plan, or create some group DC or money purchase plan. Bismarck’s intentions, instead, were to collectively force children to care for their parents during their golden years, in a dignified manner, akin to how families cared for their elderly prior to the industrial revolution. The risk was shifted from the old retiree to the young worker. Ergo, this was a pension.

It is worth noting that the Canadian system has some true pensions already. The CPP, and the Old Age Security (OAS) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement, which are Canada’s first (OAS and GIS) and second (CPP) pillars of retirement income, have the type of guarantee and risk shifting that are the hallmarks of true pensions built in. Despite the rather puny payments they provide — relative to an upper- or middle-class wage income — they are guaranteed, in real terms, for your lifetime. CPP, OAS and the GIS are pensions in the true insurance, financial and economic senses of the word. There is a counterparty to the contract, the Government of Canada, standing behind the guarantee.

Okay, so what does all of this mean from a public policy perspective? Our first thought is that while ordinary Canadians and our politicians continue to debate the merits of private versus public provision of pensions, let’s make sure everyone involved understands exactly what a pension really is. No more conflation of DB and DC pensions. And no more assuming DC pensioners are in the same boat as their DB counterparts.

Beyond this first principle, we believe it’s important for leaders to stay focused on three core discussion points:

- First, pensions are about providing a lifetime of income by pooling risk across heterogeneous groups using the principles of insurance. Pensions are not about creating financial legacies and “rainy day funds” for family and loved ones. Any focus on financial legacies is misplaced.

- Secondly, a true pension guarantees predictable income, starting at some advanced age, which matches the increasing cost of living for retirees. Hope, expectations and estimates “in all probability” aren’t enough. Canadians need certainty. Pensioners need guarantees.

- Finally, pensions must be paid for by someone. The key to the future workability of the Canadian pension system is to create a framework that allows them to be offered at the lowest possible cost in today’s dollars.

Closing thoughts: The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology tells us that the first written use of the word pension to mean a “regular payment in consideration of past services” dates back nearly 500 years, to the mid1520s; and it is derived from the Latin pensio for a “payment” or “rent” that is paid out or weighed out.

From the standpoint of 2010, we can only imagine how much the world has changed since the first pensions were conceptualized and then offered. And yet the original sense of a pension as providing lifetime income in recognition of past labour service contributions has, remarkably, retained much of its meaning over the past half-century. Perhaps this concept has remained largely intact because of its enduring usefulness to society. And reaching even further back to the Latin root of the word pension, with its sense of two parties weighing out or balancing obligations owed and payments made, we can see that the modern sense of what we are calling true pensions is perhaps not very modern at all.

As the pension debate in Canada continues to unfold, we urge participants to think carefully and clearly about what’s at stake when defining and describing pensions. The discussions we are having may not only impact you in your lifetime, but may stretch an astonishing 500 years or more into the future!

This article is an excerpt from a work in progress entitled “Pensionize Your Nest Egg,” which will be released in 2010.

Photo: Shutterstock