The hallmark reform of the 2012 budget is the change in the age of eligibility for Old Age Security (OAS) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) benefits from 65 to 67 years of age.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper indicated at January’s meetings of the World Economic Forum in Davos that Canada needed to address the implications of demographic aging on Canadian society. As he later stated in media interviews, Canada faces two key issues. Labour shortages will become more prevalent due to baby-boomer retirements and the burgeoning fiscal costs of elderly programs will need to be paid for by a relatively shrinking working population. The ratio of working age people to seniors is expected to fall from four to one in 2010 to two to one in 2030.

As reflected in this year’s budget, it is obvious that the Harper government is not one to make large changes in public policy at one time. Instead, the government takes a more incremental approach whereby objectives are laid down and an initial step taken to address an issue. Over time, successive steps add up to significant change.

This is perhaps the Canadian approach to public policy, including budgets. Except for instances such as the Martin 1995 budget, which cut program spending by 20 percent to urgently balance the books, most federal governments have made incremental changes year by year.

A good example is business tax reform, which has been an important part of budget policy-making at both federal and provincial levels since 2000. Unlike the big bang of Reagan tax reform of 1986, which resulted in the reduction of the US corporate tax rate from 48 to 35 percent and a 1,000-page book of base-broadening changes implemented in 1987, Canadian Liberal and Conservative governments used 12 budgets to reform Canada’s business taxes, which moved Canada from having the highest tax burden in 2000 to having a competitive advantage among OECD countries in 2012. The federal-provincial general corporate income tax rate fell from 43 percent to 27 percent by 2012. In a politician’s life, 12 years is almost eternity.

This Budget 2012 OAS/GIS change is not a “big bang,” whereby the government takes on a host of issues to deal with the demographic pressures facing Canada in the next two decades. There is no grand plan to reform health care, long-term care, the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and various tax measures such as the aged credit, pension income credit and private pension and registered retirement saving plans, over time. Instead, one change is introduced, and that is with respect to OAS and GIS costs.

The initial reaction of Canadians to the Prime Minster’s Davos remarks was puzzlement. After all, the federal-provincial-territorial ministers of finance were given a report on retirement income adequacy that I had prepared for them in December 2009 that declared the pension system was financially sustainable. If this was the case, then why change OAS if its costs were to increase from 2.3 in 2010 to 3.1 percent of GDP in 2030 — a significant jump but not a barnburner compared to other pressing matters?

Changing the age of eligibility for OAS and GIS is a sensible move at this time to address the overall demographic pressures that face Canada as a whole. Age-related spending in Canada is expected to rise by 7.7 percent of GDP, according to an IMF 2009 report. However, what is often left out is that the tax-GDP ratio will also fall as the number of retired people increases relative to the working population. In years of retirement, people pay less income, payroll and sales taxes to governments compared to working years. Therefore, Canada will have fewer tax dollars to fund growing spending pressures related to aging.

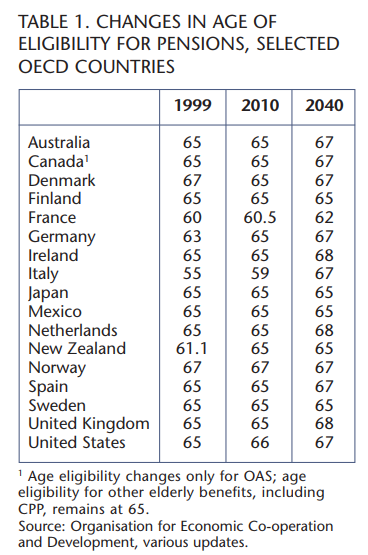

Thus it is inconceivable we would maintain an eligibility age of 65 when people are living longer past that age. Some countries, such as the Netherlands, have indexed their age eligibility requirement for social security by the expected life calculations — the longer that people live the eligibility age for social security automatically increases (table 1).

Moving first on OAS and GIS also makes sense in another respect — it is easiest for the federal government to make unilateral changes to the age of eligibility. CPP reform is stalled, since any amendments to the program would require agreement not only of the federal government but also of seven provinces representing two thirds of the population. With Alberta and Quebec both lukewarm to CPP amendments, in fear of higher costs, any changes to CPP are distant. Other changes such as revamping the aged and pension credits would be difficult to implement unless they were staged at a later time, when the age of eligibility is increased for other programs as well.

The budget will increase the age of eligibility to claim OAS and GIS from 65 to 67, beginning in 2023 with a phase-in period lasting six years until 2029. The allowance and allowance for spouses provided to low-income seniors between the ages of 60 and 64 will also be adjusted to reflect the higher age eligibility for OAS and GIS.

Further, the government announced that seniors who defer taking OAS up to five years after the age of 65 are eligible for a higher actuarially adjusted OAS payment. This adjustment is similar to that used for the deferral of CPP payments.

Even though the change to age eligibility has no impact on those 55 years of age or older, the announcement is significant. Canada is joining a long list of OECD countries that have increased the age of eligibility for social security payments. In several instances, the age of eligibility of 67 years has now become the “normal” case (Australia, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway and the United States have already implemented it). Many other countries that had relatively low ages of eligibility have jumped them up sharply in recent years from 60 to 65 years of age, including France, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

Countries that have increased age eligibility have followed the same approach that Canada has now adopted. An announcement is made years in advance of implementation, and there is a phase-in period as the age is increased. In the United States, the increase in the eligibility age from 65 to 67 was announced in the Clinton years 10 years ahead of time, with a phase-in to take place over the following six years.

As some have cynically observed, long lead times before implementation make it politically easier to change the age of eligibility for senior pensions since the baby boomers are not affected. However, in policy terms, it is a wise move. Current seniors receiving entitlements are on fixed incomes, and those close to retirement have already made most of their saving decisions for retirement. It is hard to change the rules of the game on the existing elderly by lowering pension payments without creating hardship for those who have less flexibility.

With an expectation that OAS and GIS will not be available until the age of 67 after 2029 (with the phase-in starting in 2023), Canadians under 55 years of age will need to consider building up their own retirement income more than expected. They could do this in two ways.

The first way is obviously through saving more. The government has been expanding pension and RRSP contribution limits in recent years as well as introducing tax-free saving accounts that enable more saving to be sheltered from personal income taxation. The expected reduction in OAS for those under 55 today should encourage Canadians to set aside more of their income for retirement purposes. So instead of OAS being funded from taxes paid by future workers, current workers will have to fund the benefits themselves. There is clearly nothing wrong with the idea of putting more onus on individuals to plan for their own retirement. It also has the benefit of increasing saving that can be available for ownership of Canadian and foreign assets that boosts the economy in other ways.

The second response is for people to work longer than planned. As Canada enters into an era of labour shortages as the boomers retire, it is clearly important to remove any regulatory and tax barriers to work. Therefore, increasing the age of eligibility for OAS will create more incentive for people to postpone their retirement. Further, the actuarial adjustment for OAS payments for those who defer could encourage some people to work beyond 65 years of age since they can get more OAS when they stop working at a later age, an amount that would otherwise be “repaid” under the income tax for higher-income seniors. In the Mirrlees tax reform report (published by the UK Institute of Fiscal Studies), it was estimated that retirement decisions are quite sensitive to changes in fiscal parameters. Changing age eligibility for government-provided senior benefits could have an important impact on labour supply.

Countries that have increased age eligibility have followed the same approach that Canada has now adopted. An announcement is made years in advance of implementation, and there is a phase-in period as the age is increased.

For those who are under 55 years of age today, the reduction in elderly benefits payments starting in 2023 could be problematic for low-income Canadians who have difficulty maintaining a job for health and other reasons. The allowance (and spousal allowance) would kick in at the age of 62 (instead of 60) so this will soften the impact of GIS postponement to the age of 67. For those younger than 62, governments could be faced with somewhat higher costs for disability and social assistance support for nonworkers. An alternative to higher social assistance is to provide a longer period for the allowance and spousal allowance eligibility (perhaps with some reduction in payment on an actuarially fair basis as with CPP when benefits are claimed earlier than 62 years of age). Well, at least we have a decade to sort out these issues related to senior poverty.

The increase in the eligibility age for OAS and GIS could be the first of many changes both at the federal and provincial levels to cope with the pressures of an aging society. Policy can change in two directions: the first is to reduce economic and fiscal costs where it makes sense to do so, and the second is to expand support for the elderly where it is needed.

With respect to OAS benefits, the federal government has other levers to reduce their costs. Under the existing system the OAS benefit in 2012 is repaid to the federal government when a senior’s income is more than $69,562(the repayment is 15 cents for each additional dollar of income received in excess of the threshold).

Simply de-indexing the threshold for inflation would result in more and more relatively better-off Canadians paying back more of their OAS to the federal government. This could make more money available for other senior support programs.

Increasing the age of eligibility for elderly benefits makes sense in other cases as well. Under the existing tax system, the aged credit and pension income credit could be amended so that they cannot be claimed until the age of 67 starting in 2023. The eligibility age for some other programs, such as provincial drug programs, could be changed as well.

In recent years, federal and provincial governments have also been looking at a possible enhancement of CPP by increasing benefits (and payroll taxes to pay for the benefits). As several studies have shown, about one-fifth of Canadians with modest incomes ($30,000 to $50,000) seem to have insufficient saving at the age of 65 in retirement, housing and other assets, for a variety of reasons. Changing the age of eligibility for CPP from 65 to 67 could help pay for some expansion of CPP itself.

Retirement income is not the only issue that is affected by an aging society. As the elderly grow in size relative to the population, there will be a need for more health, disability and long-term care services. Many people will need to rely on their own and family resources to assist them in their elderly years, but governments will likely face political pressure to support lower-income Canadians. Again, a shift to a higher age for eligibility for many senior programs will relieve these other pressures by freeing up tax dollars.

Tax reforms will also need to be considered as the population ages.

Canadians should have a longer period before they need to cash in their RRSPs to support their retirement — the existing age of 71 was in place at the time the RRSP system was created. Now that Canadians live longer, they should be able to keep RRSP wealth reinvested for a longer period (such as until 75 years of age). Existing tax breaks like the pension income credit (which has little rationale) should be discarded over time. And governments should avoid raising income and payroll taxes on working populations who will need to bear a bigger share of elderly program costs in later years.

In my view, the changes to the OAS and GIS are simply a continuation of past policies that deal with various demographic pressures. Canada became engaged in debt reduction in the 1990s to reduce the burden left to future generations. The 1997 changes to CPP were an important step to ensure benefits are fully funded for the next 75 years, as Budget 2012 reminds us. Changing the eligibility age for OAS and GIS was another step that makes sense. There will be more policies to come — and the Harper government approach is to take them one by one as required.

Photo: Shutterstock