Services haven’t traditionally been viewed as an export that can be traded across international borders. But this outdated view of trade is changing. We now have a better understanding of the important role that services play in manufacturing activities and the overall economy. Technological progress is also making it easier to trade services across long distances.

This week the IRPP released two new chapters from our forthcoming research volume Redesigning Canadian Trade Policies for New Global Realities. These chapters focus on services and why they matter for Canada’s trade.

The first reason is obvious: size. Services represent the majority of economic activity, accounting for over three-quarters of Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) and employment. As such, the efficiency of our services sector is a key determinant of the country’s overall competitiveness.

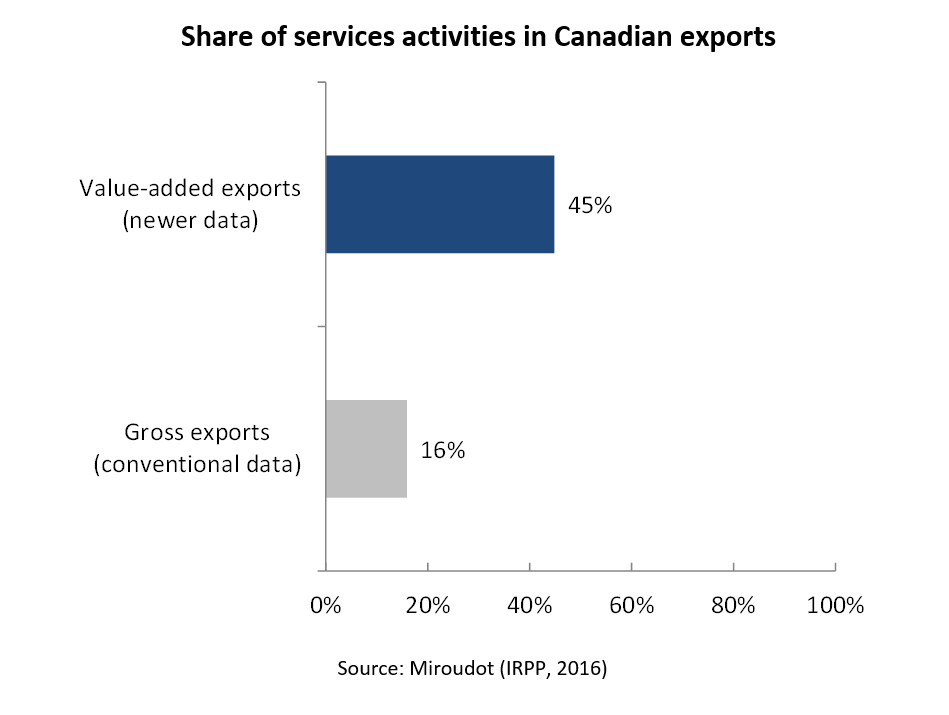

The second reason is less obvious: many services that Canadians sell abroad aren’t recorded as exports. This is because services — such as transportation, finance, telecommunication, research and development, and others — are embodied in the goods that we export. Only recently have measurement techniques revealed the true contribution that services collectively make to our international trade (on value-added trade data, see De Backer and Miroudot, in our volume). For every $100 worth of products that Canada exports, this research estimates that $45, on average, goes to services activities. This is about three times larger than what’s recorded in conventional (gross) trade statistics.

Another wrinkle in this “hidden value-added” explanation is that businesses often require a local presence to effectively sell services abroad. Increasingly, this occurs through Canadian foreign affiliates located in other countries, which have taken on a larger — though still under-appreciated — role in Canada’s global commerce over the past decade. (One example would be a Canadian bank branch located in the US). In fact, by 2012, the value of Canada’s foreign affiliate services sales overtook that of foreign affiliate goods production and were about twice as large as Canada’s services exports (see Koldyk et al., in our volume).

Next, consider growth. Looking back over the past decade, Canada’s international services trade has grown faster than its goods trade (in addition to being less volatile), with particular strength in key sectors such as finance and insurance, management services and computer and information services (see Palladini). Looking ahead, the next stage of the “industrial revolution” is largely expected to be rooted in services, with products relying increasingly on intelligent devices, networked sensors, big data analytics and machine learning. In this environment, the countries that adopt policies to facilitate the seamless provision of services and data across international borders stand to benefit most from these developments and new business models, attracting high-value services activities.

So is Canada’s policy stance helping or hurting its services trade?

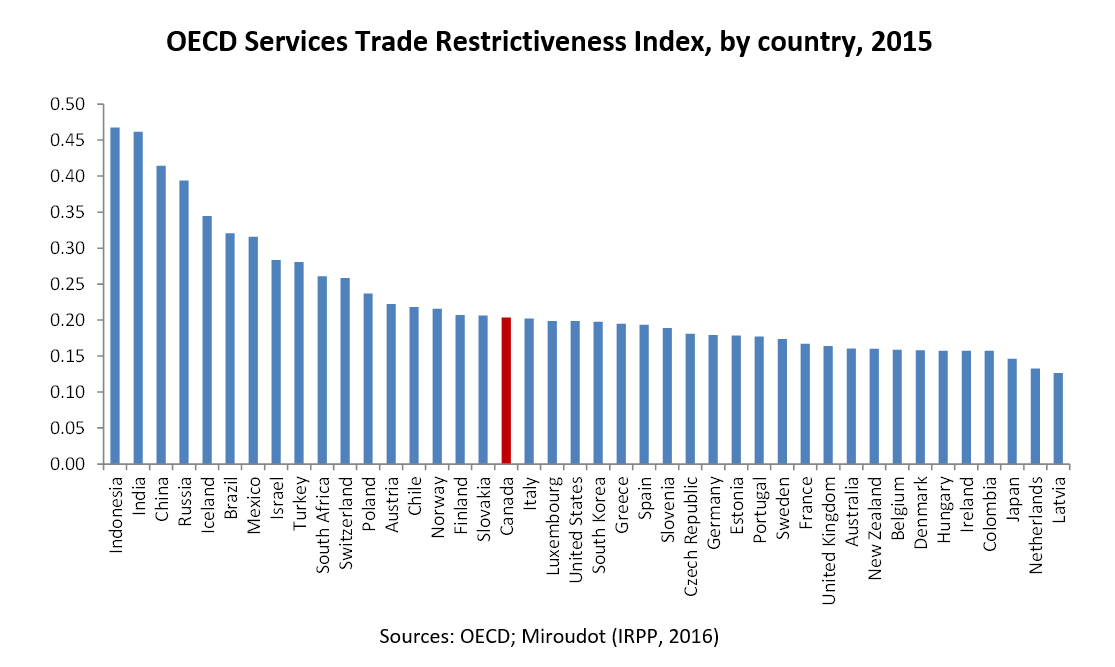

Sébastien Miroudot’s chapter compares the restrictiveness of Canada’s services trade policy in an international context. His work uses the OECD’s Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), a database that identifies trade barriers based on laws and regulations currently in place in 42 countries (the 34 OECD members, plus major emerging economies). A domestic market completely open to foreign trade and investment would score zero by this system; a market completely closed to foreign services providers would score 1.

The figure below shows the average STRI scores for these countries in 2015. Canada ranks around the middle of the pack; the least restrictive countries for services trade are Latvia and the Netherlands, while the most restrictive are the major emerging (BRICs) economies.

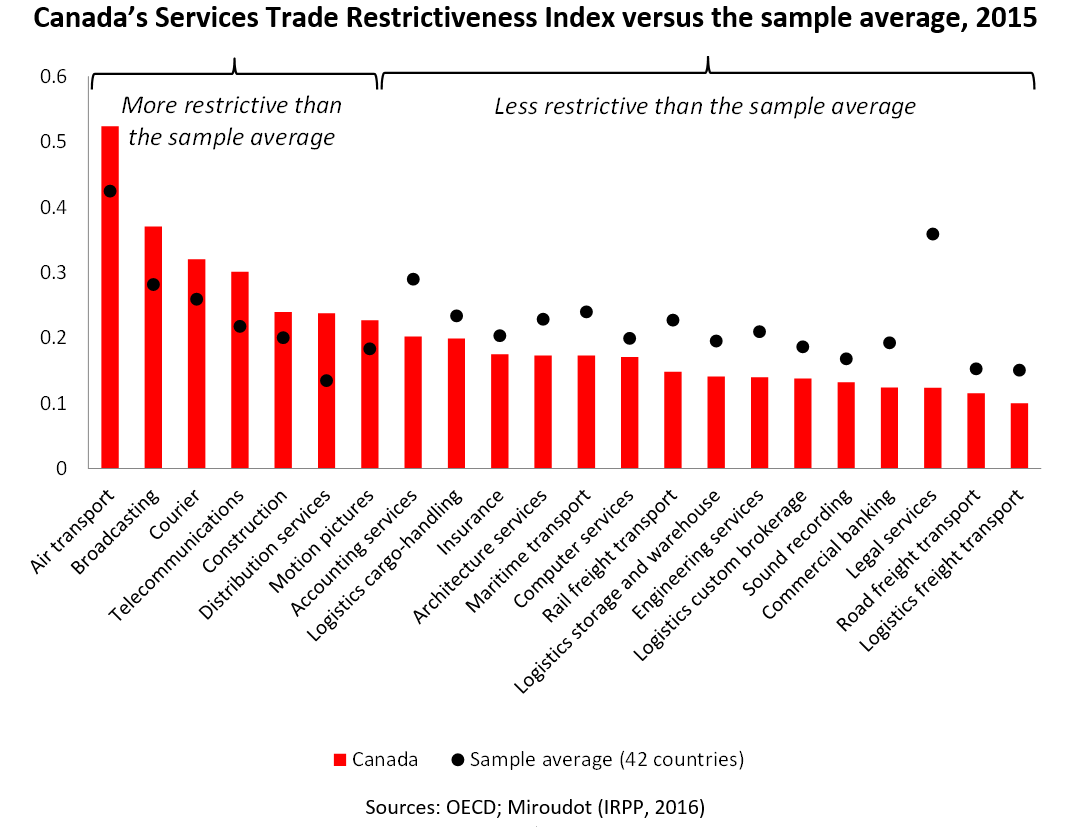

Beneath these country averages, the restrictiveness of services trade varies significantly by sector. In most cases (15 out of 22 sectors), Canada’s policies are less restrictive than the sample average. For instance, Canada has a relatively open trade regime for foreign professionals, particularly in legal and engineering services (where there are no nationality/residency requirements and where a transparent and competency-based system recognizes equivalent education degrees). Canada also has fewer restrictions in accounting, insurance, architecture and computing, among others.

But Canada has higher-than-average barriers in air transportation, broadcasting, courier, telecom, construction, wholesale and retail trade and motion pictures. Some sectors — such as transportation, finance and telecom in particular — are also used as inputs by other industries. Increasing competition in these “networked” service sectors, which are essential drivers of productivity, would have broader positive spillovers for the Canadian economy.

It turns out that most of Canada’s reported barriers in services deal with foreign entry and the treatment of foreign investment. In all sectors of the economy, at least 25 percent of the board members of corporations must be Canadian residents or citizens. In addition, in sectors where the Investment Canada Act applies, investments are subject to screening — whereby foreign investors acquiring Canadian businesses that are valued above established thresholds must show likely net benefits to Canada, while domestic investors have no such obligations.

The chapter identifies some domestic policy actions and sectors that Canada could focus on to improve its broader economic performance. Still, it is important to recognize that the rules governing international trade in services increasingly are being negotiated through large regional trade agreements. For instance, services feature prominently in Canada’s recently concluded Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the European Union and in the 12-country Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Canada is also currently involved in the 50-country Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA).

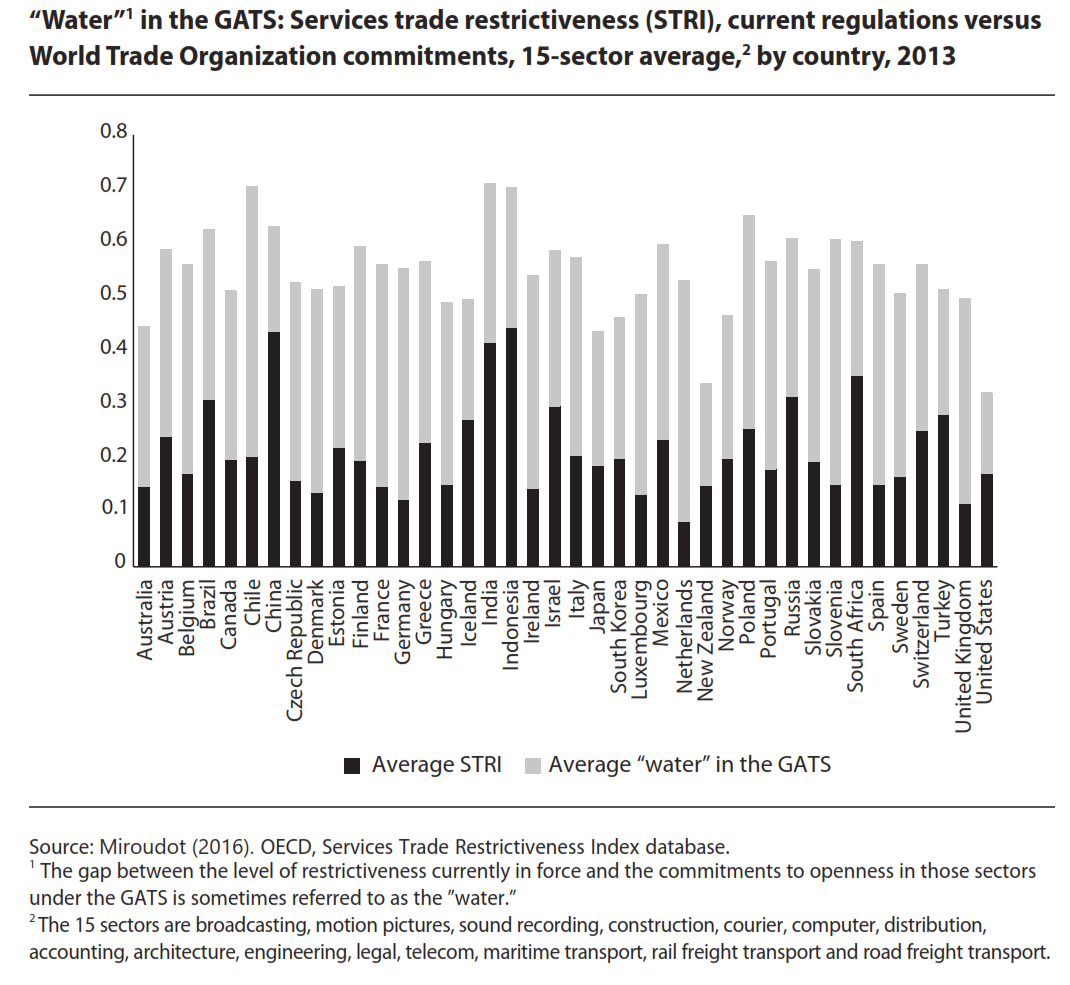

Miroudot also points out that in Canada — and in other countries — the legal regime for services trade needs to be updated. That could be done by committing in international agreements to mirror the openness of the trading regime that is already used in practice (and is already more liberal than are the World Trade Organization’s General Agreement on Trade in Services commitments, see the figure below).

In his chapter, Erik van der Marel analyzes the potential to enhance our services trade through the big trade agreements that Canada is involved in. He finds that the country groupings in CETA, TiSA and the TPP are all pretty good fits for Canada, considering the services we tend to export and those the other trading partners import.

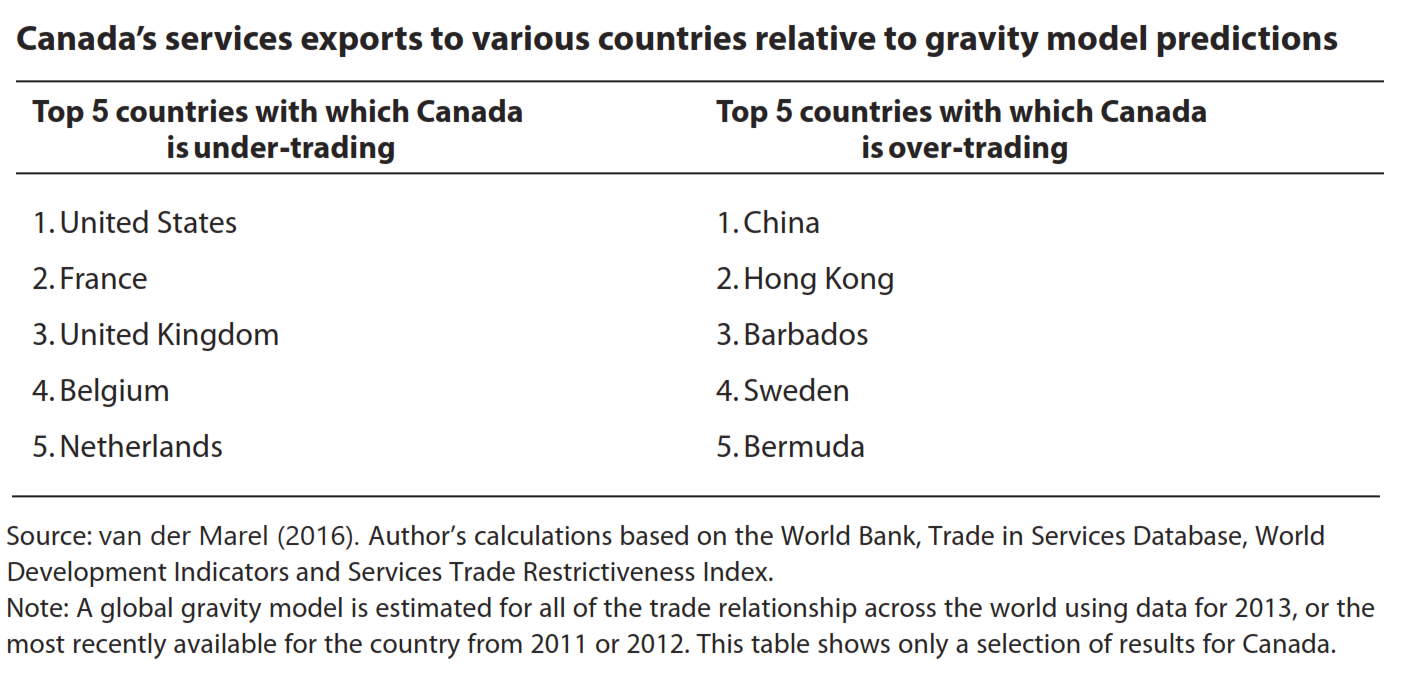

He also examines the potential for increased services trade using so-called gravity analysis, which predicts countries with which Canada is under-trading and over-trading services. The table below reports the top 5 countries in each category for Canada.

(This approach estimates how much a country’s exports differ from the gravity model’s predictions based on factors such as distance, the size of the country’s GDP and endowments such as the quality of the labour force, infrastructure and the regulatory environment, all of which also affect trade costs. If Canada exports more services to a country than the model predicts, it is said to be over-trading with this partner; conversely, Canada is under-trading when observed trade is below the model’s predictions.)

These results suggest that Canada has the potential to expand its services exports to the United States (even though we’re already quite active in that market) as well as with several members of the European Union, most notably France and United Kingdom (countries where Canada currently is far less active). Conversely, we may already be overtrading with China and Hong Kong, as well as with some tax havens (such as Barbados and Bermuda, likely related to financial services flows from Canada to these countries).

In terms of pursuing these gains through trade negotiations, van der Marel says that Canada’s services trade would benefit from implementation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership — most notably with the United States. Naturally, CETA could improve Canada’s services trade with the European Union, even though several sensitive sectors were essentially kept off the negotiating table. Finally, TiSA could expand market access to a much broader set of countries, although the ultimate level of ambition in this deal remains to be tested.

The emergence of global supply chains, the increasing role of services as drivers of productivity, and new evidence on how the services trade is embodied in goods, are trends that highlight the need for new policy and reforms. These new chapters by Miroudot and van der Marel are a useful resource for readers interested in the sectors that Canada should focus on to reform its services and investment policies, and which countries and negotiating venues are most promising to pursue these gains.

In the next chapters we will release, coming up in September, we will look at Canada’s outstanding trade negotiations and overall strategy, and we will examine the TPP rules (of origin) for goods trade. If implemented, the TPP would help weave together the different rules from a variety of previous, overlapping trade deals among the partner countries.

Photo: 06photo/Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.