The federal government has seized the opportunity to sharply increase immigration levels in its response to the COVID-19 pandemic’s radical altering of global migration and the free flow of people.

Most of Canada’s immigration programs have recovered from the depths of COVID-19 health and travel restrictions. Over the last two years, the government has adapted by expanding online applications and modernizing its application processes.

Nearly two years of data and policy responses show that since 2021, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) has given priority to urgent labour-market needs along with facilitating international students. But the sharp increase in immigration levels has been a long-standing government desire. (“Never let a good crisis go to waste,” goes the saying credited to Winston Churchill).

As we enter the third year of the pandemic, the time is opportune for Canada to assess the impact on immigration-related programs, the government response and the degree to which these programs have recovered.

This analysis contrasts pre- and post-pandemic programs for the period 2018-21 across permanent and temporary immigration, international students and citizenship, comparing web traffic (with particular search terms regarding interest in immigrating, working, studying and settling in Canada), applications (action) and admissions (result) across the top 10 source countries.

Can Atlantic Canada benefit from immigration?

Canada needs to improve its immigration channels for essential migrant workers

Immigration and related programs are driven by a complex set of push and pull factors that incentivize migration – something Howard Ramos and I noted in February 2021, in our Policy Options article Will the pandemic make Canada less attractive to newcomers?

Canadian immigration response involved short- and longer-term measures, the common thread being increased online applications and processes:

- Addressing the immediate need for temporary workers in essential sectors such as agriculture by providing exceptions to travel restrictions.

- A special pathway for international student graduates from Canadian institutions, health-care and other essential workers to become permanent residents.

- Greater flexibility for international students to continue their studies remotely.

- Increase in the number of permanent-resident admissions, largely from temporary residents (students and others) already in Canada (two-step immigration).

- Temporary shutdown of the citizenship program, restarting with remote citizenship assessment and ceremonies.

- Major reduction in visitor visas, reflecting travel and related restrictions.

One consequence of these changes was increased backlogs of applications: 448,000 applications for citizenship, 519,030 for permanent residency and 848,598 for temporary residency.

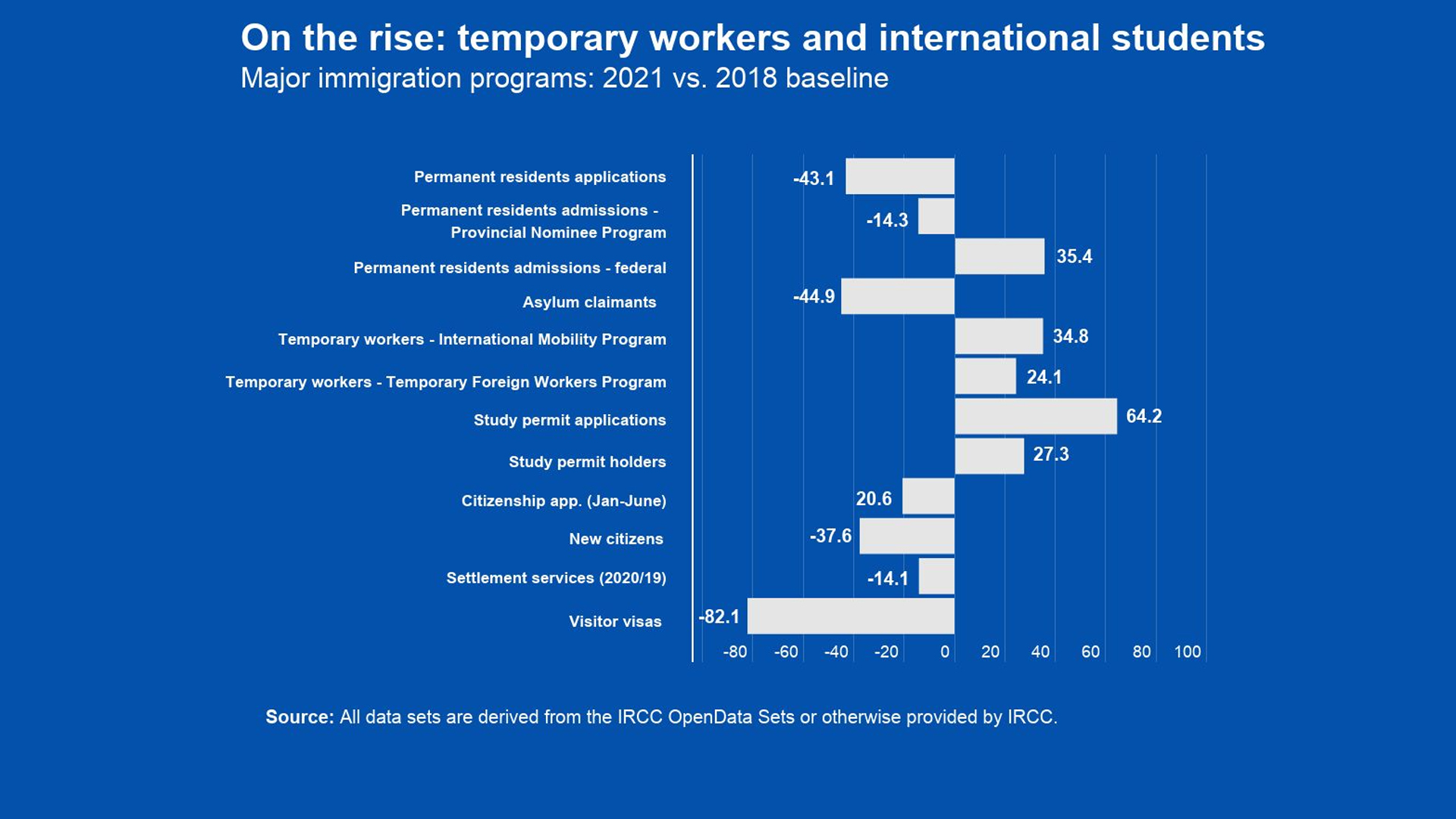

In the context of the overall government objective of increasing immigration, Figure 1 highlights the relative priorities of the government, with the highest priorities being for federal new permanent residents (listed in the chart as “PR Admissions – federal”) and the feeder groups of temporary workers and international students. The decline of permanent residency applications reflects delays in application data being entered into the main IT system.

In contrast, asylum claimants, citizenship, settlement services and visitor visas (the program most affected by travel restrictions) all declined.

Permanent residents

Figure 2 contrasts permanent-resident web interest, applications and admissions by country.

Use of the online search term “immigrate to Canada” remained stable, increasing from 4,827,000 to 4,970,000 or by three per cent from 2018 to 2021. Applications, which demonstrate real interest, declined 43 per cent, from 412,000 to 234,630, partly reflecting application entry delays.

The number of permanent residents admitted to Canada increased from 321,000 to 404,000, or 26 per cent. While immigrants nominated by the provinces (provincial nominee program) were down by 14 per cent, federal economic class immigrants were up by 60 per cent, family class down six per cent and refugee class up 25 per cent.

To meet the target of 401,000 permanent residents, there was a radical shift toward enabling temporary residents to become permanent residents (TR2PR), which increased from 92,000 to 279,000 or 203 per cent. The international mobility program (IMP) was up 205 per cent (mainly intra-company transfers, spouses and post-graduate employment), the post-graduate work program was up 260 per cent, the international students

program was up 107 per cent and the temporary foreign work program (TFWP), which includes caregivers, agriculture workers and skilled workers) was up 137 per cent.

Most of the increases in permanent residents are due to “feeder groups” of temporary residents (mainly IMP) and international students, with their share increasing from 29 to 69 per cent of all admissions.

Temporary residents

Figure 3 contrasts web interest in temporary residency with admissions for IMP and TFWP by country.

Web traffic for the search term “get a work permit” declined from 972,000 to 839,000 or 14 per cent.

Work permits issued under the IMP increased significantly, from 219,000 to 295,000, or 35 per cent, with the greatest increase grouped under Canadian interests (intra-company transferees, spouses of skilled workers and post-graduate employment, for example). That number rose 28 per cent, while those grouped under agreements (e.g., the Canada-United States-Mexico pact and other free trade agreements) declined by 18 per cent. The “other IMP participants” (people with unstated program codes or those in special programs and measures introduced in 2021) rose by more than 139,000 per cent, reflecting an extremely small base in 2018 (only 20 compared with 28,000 in 2021).

More agricultural workers should become permanent residents

COVID-19 exposed the urgent need for an agri-food labour strategy

Work permits issued under the TFWP increased less than those under IMP, from 85,000 to 106,000, or 25 per cent. Caregiver work permits declined by 18 per cent. The number of agriculture workers rose by 14 per cent and skilled workers by 59 per cent.

Students

Figure 4 contrasts student web interest, applications and admissions by country.

Web traffic for the search term “get a study permit” in Canada increased by 40 per cent, from 704,000 to 983,000.

Study permit applications also increased dramatically, from 340,000 to 558,000, an increase of 64 per cent while study permits increased by a lesser extent, from 369,000 to 469,000 or 27 per cent. Studying in Canada has become an increasingly popular way to immigrate to Canada.

Citizenship

Figure 5 contrasts citizenship web interest and the number of new Canadian citizens by country of original citizenship.

Web traffic for the search term “apply for citizenship” declined from 373,000 to 267,000, or 28 per cent.

The number of citizenship applications from January to June declined from 143,000 to 114,000, or 21 per cent (full 2021 data not available).

The number of new citizens declined from 176,000 to 131,000, or 26 per cent, with only new citizens from India increasing while those from Jamaica were largely unchanged.

What will the long-term impact be?

COVID-19 health and travel restrictions forced IRCC to accelerate the use of online applications and staff processing tools, and to change policy to recognize remote study and work.

The government priorities were clear: address the pressing need for temporary workers in the agriculture sector and support education institutions by allowing international students to qualify for post-graduate employment despite part of their studies being abroad.

Lesser priorities such as citizenship took more time to adapt.

Immigration policy requires a rethink

Governments’ use of AI in immigration and refugee system needs oversight

Canada’s COVID-19 blind spots on race, immigration and labour

The pandemic did not change the overall increasing trend for Indian immigrants, students, international mobility temporary residents, and citizenship. Other countries showing increases for most programs include France, Iran and Nigeria. China, in contrast, remained flat or declined.

What remains to be seen is the longer-term impact of these policy choices, particularly favouring those already in Canada as a preferred source of new permanent residents, along with the related increase in backlogs.

Future evaluations and data will indicate the extent to which the government’s approach succeeded in terms of overall economic and social outcomes.

Methodology:

Data is taken from public data tables on Open Data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) for the years 2018-21 as part of a project to track changes in immigration and related programs due to the pandemic, along with the impact of the government’s policy and program response. In some cases, (settlement services and citizenship applications, for example), this data has been supplemented with other IRCC data along with its website data. I will be continuing this analysis in 2022.

Where available, the data includes web searches, applications and admissions to contrast general interest and enquiries, serious interest in submitting applications, and actual entry.