Access to sustainable, affordable bandwidth sufficient to meet the needs of health, education, economic development and emergency services is critical. Last March, as British Columbia entered into a state of emergency, it included internet and telecommunications in the list of services that must continue to be delivered during the pandemic, as “essential to preserving life, health, public safety and basic societal functioning.”

But for many First Nations communities in B.C., that essential access to virtual health services, virtual classrooms and internet access for thousands of local businesses was not a given.

There are 203 First Nations in British Columbia, and these First Nations encompass an additional 307 secondary occupied (on-reserve) communities. The size and locations of these communities vary widely, and the terrain in most cases could be kindly described as challenging. The more isolated the community, the greater the need for digital connectivity. The more challenging the access to transport, the greater the cost and therefore the fewer options for solutions.

Thus, a nimble and diverse approach to achieving digital connectivity is required to address this demographic.

Building pathways to high-speed access

Pathways to Technology, a project managed by the All Nations Trust Company (ANTCO), is an initiative to bring affordable and reliable high-speed internet to all 203 First Nations in B.C. It funds infrastructure builds and negotiates agreements that obligate internet service providers (ISPs) to charge fair prices and perform ongoing maintenance and upgrades.

In smaller and more remote communities that cannot feasibly be served by large ISPs, however, we have to seek alternate solutions involving either small carriers or, in some cases, First Nations acting as their own ISPs. The scope, the complexity and the sheer ambition of this project make it the largest and most complex First Nations connectivity initiative in the country.

In these latter situations, First Nations manage their own “last mile” networks and pay carriers for ”transport” to the community. First Nation-owned ISPs are then faced with the inherently conflicting goals of delivering affordable high-speed internet while also generating enough revenue to cover ongoing costs of transport, maintenance and upgrades. More often than not, cash flow is insufficient and over time networks degrade so much that speed and bandwidth fall below ever-increasing standards. A lack of available funding for ongoing operations has unfortunately led to this outcome in several of Pathways’ connected communities.

Conversely, in scenarios where large carriers act as the ISP and residents subscribe for high-speed internet from these ISPs, networks are sustainable, but affordability is a barrier.

In both scenarios, certain First Nation communities find themselves with no good option. First Nations acting as the ISP enables the delivery of affordable high-speed internet but inevitably leads to network sustainability issues. Having a large carrier act as the ISP solves sustainability issues but comes with affordability challenges. A further hurdle exists in both cases, as many homes lack access to computers.

Information gathered by Pathways to Technology about First Nations in B.C. that were connected over the past eight years reveals that 50 per cent of them now require a major upgrade to meet the CRTC standards for acceptable community connectivity. Desired and needed bandwidth may not be affordable or sustainable.

The scope of Pathways’ original mandate was limited to providing each community with a single point-of-presence or POP (a network access point). This meant connecting First Nation communities at the “seat of government;” that is, the community where each nation’s main office is located. This means many outlying communities are still left without service.

Engagement is key

As some have observed, “if you’ve seen one First Nation…you’ve seen one First Nation.” The key ingredient in meeting the communities’ needs for internet services is engagement: ensuring communities’ specific needs are heard and addressed, and solutions are tailored to meet these needs. Carrier Sekani Family Services (CSFS) Society is just one example of a project that sought to align the goal of digital connectivity with the basic historical principles and values of that tribal group.

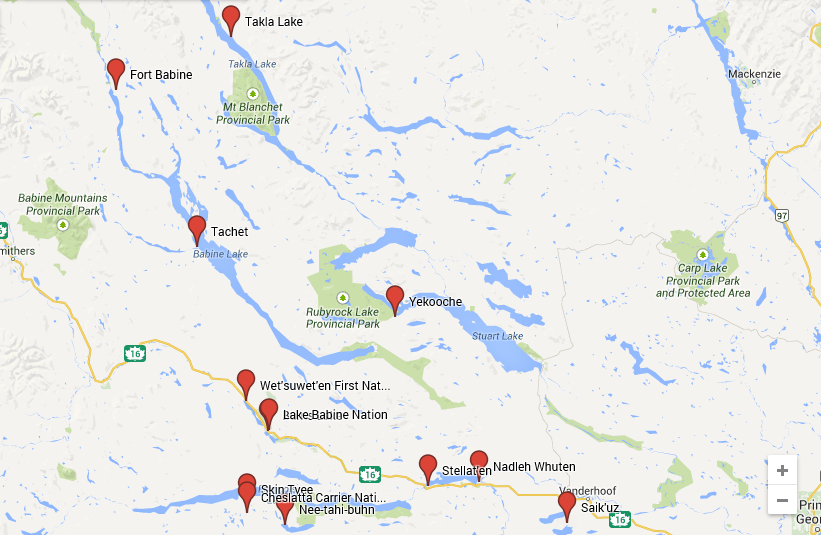

In that case, the CSFS Society needed fair access to culturally sensitive health and telehealth services during the pandemic, regardless of the community’s location. The 12 communities it serves are spread out over large territory. For example, the community of Takla Lake is 400 kilometres from the central services of CSFS out of Prince George.

To accomplish this, a co-ordinated, creative and co-operative approach for the provision of bandwidth was required. The approach had to have the capacity to respond recognizing the values and principles of the Carrier and Sekani peoples and delivery of health services respecting their law of sharing, and delivered using the principles of respect, responsibility, compassion, wisdom, caring and love. This was a great example of a community-driven centralized solution – the design was led by CSFS, and the outcome was the delivery of broader service.

The need for targeted funding

Funding agencies need to understand the needs of First Nations and be familiar with where they are located. For this reason, Indigenous Services Canada should oversee specific funding for broadband internet for First Nations. Currently, such funding does not flow from a specific broadband fund, but from the First Nations Infrastructure Fund that touches on seven other types of projects.

All First Nation communities in British Columbia should have sustainable and affordable access to high-speed internet that can be relied upon in crises like the one we face today with the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, more than ever, high-speed internet is essential to their short- and long-term viability.

For more information about the Pathways to Technology project, please visit the website at www.pathwaystotechnology.ca

This article is part of the Digital Connectivity in the COVID Era and Beyond special feature.