This year’s federal budget committed another $1 billion to expand “access to fast and reliable high-speed internet.” Many Canadians who are already connected to high-speed internet are making significant household budget trade-offs to afford it. There are more home internet users in the lowest income quartile than there are households across Canada that don’t have access to high-speed broadband.

Currently, the focus of telecommunications policy discussions in Canada is on why and how competing service providers should benefit from infrastructure facilities and radiofrequency spectrum. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s (CRTC) recent review of mobile wireless services, and pending decision on rates for wholesale high-speed access, are examples of this preoccupation. In public discourse, access to telecommunications infrastructure is perpetually confused with connectivity – consumers benefitting from using it. The latter is clearly the goal if we are concerned with sustainable development, and attention should focus on affordable service provision as much as infrastructure.

Connectivity inequities exposed

Home internet is critical to lives and livelihoods. People with young children are more likely to have switched to working from home during the pandemic. The past year has exposed existing and intersecting social divides, including inequities related to connectivity – digital divides. The loss of access to Wi-Fi in public libraries, for example, has made it more obvious that people must also have a connection at home, and that bandwidth and device availability are important considerations. Public health crisis notwithstanding, reducing trips and transit time to spaces such as libraries, while working to ensure everyone has a reliable home internet connection, would allow more people to stay connected and benefit from educational and labour market opportunities.

As in the U.S., about 95 per cent of people in Canada do benefit from internet use at home. Among low-income households, the number is perhaps ten percentage points lower. Age, location and education determine connectivity levels, and in the divide between those with and without internet service subscriptions, the most often-reported reason is affordability.

When the market rate for internet is unaffordable

The average price for broadband in rural places in Canada is higher than in urban areas. We do not have a federally mandated obligation to ensure all citizens are connected. The CRTC’s oft-cited “50 megabits download, 10 megabits upload, unlimited data” is a target for broadband availability, not for how many people will adopt the service. A significant number of households for which internet services are available don’t subscribe for reasons of affordability. Households in the lowest income bracket who do subscribe to the internet pay a market rate rather than a means-tested rate for telecom services that are key to education, employment, commerce, communication and health.

There must of course continue to be infrastructure investment to get broadband supply to the remote and rural Canadian households the network doesn’t yet access. The Universal Broadband Fund’s (UBF) now $2.75-billion investment aims to reach 98 per cent of Canadians by 2026, and the remaining two per cent by 2030. Projects are under way, drawing on various active public-private funding programs, and more are announced regularly. While these facilities are fundamental, it’s what happens after access that matters most to human development. Network infrastructure is the mechanism, not the intended outcome.

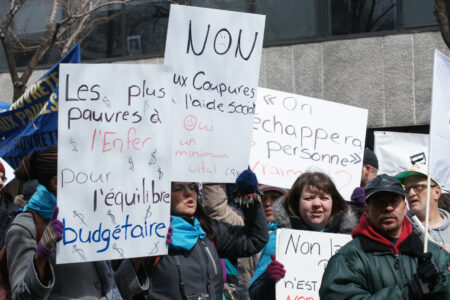

Competition and regulation are driving down prices, but there is a floor the market will land on with a substantial portion of people in Canada below it, unable to afford services due to income inequality. In other sectors where market prices are unaffordable for some, low-income populations benefit from public instruments supporting housing, child care, transit and utilities such as electricity. Yet, when they subscribe to telecom services, people in the lowest-income quartile spend up to twice as much of their budget on it as middle-income households.

As with social housing, to achieve broadband affordability, governments could invest in building telecom infrastructure for people who are underserved, as well as providing ongoing services at off-market rates. Means-tested rates are currently offered to some households in Canada. In addition to their own digital inclusion programs, service providers – big, medium, and small – are together voluntarily participating in the federal government’s Connecting Families initiative. This is not a subsidy program. No public funding goes to the companies to offset the costs of having served more than one million cumulative months of $10 internet through the initiative.

As policy-makers consider affordability options, they should continue to foster service-provision innovation. On the wireless side, at least one regional brand, Quebecor’s Fizz, is demonstrating a technology-forward low-price offering. On the home internet side, taking inspiration from recent pilots, affordable service for targeted populations could be delivered through community clusters – innovative coalitions including governments, service providers and community organizations.

Finally, wholly public internet schemes do exist in communities across Canada, with major municipalities now kicking the tires as well. Such a “utility” model for telecom services in urban centres would in many cases require appropriating the underground conduits for fibre optics, cabling new access into homes, and perhaps most important to high-quality service, competing with private sector providers for architectural and operational talent. Public investment in infrastructure parallel to existing private facilities is not a short-term project. Multisector service coalitions and/or subsidy programs for low-income households may be a more efficient path to affordability.

Much of the conversation around digital divides focuses on what is lacking – what portion of people in Canada aren’t connected, or whether what you get here in Canada is cheaper somewhere else. We must continue to invest in providing choices for those who don’t have them, while recognizing with compassion the difficult choices already being made by many.

This article is part of the Digital Connectivity in the COVID Era and Beyond special feature.