Experts agree that carbon taxes intended to combat global warming could most efficiently be imposed upstream or midstream in the production-distribution process for fossil fuels. In the case of domestically produced fuels this would be at the mine mouth for coal, at the refinery for petroleum, and at processing plants or pipelines for natural gas. (To simplify exposition, this is hereafter called upstream taxation of fuel.) If fuel imports were taxed, but fuel exports were not, upstream taxation of fuel would produce the same economic effects as taxation of emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) or a cap-and-trade system, but it would be much simpler. By comparison, Thomas Courchene and John Allan, in the March 2008 issue of Policy Options, have suggested instead the use of a downstream “carbon-added tax” (CAT) patterned after the value-added tax (VAT, known as the goods and services tax or GST in Canada). This apparent anomaly is explained by two words, “border adjustments.”

Under upstream taxation of fossil fuels, taxation of emissions or a cap-and-trade system, non-fuel products would bear the “carbon price” — the carbon tax or the cost of emissions permits — of the nation where they are produced, not that of the nation where they are consumed. (The remainder of this article generally omits references to the economic effects of cap-and-trade systems, which are broadly similar to those of a tax on emissions.) Such origin-based (or production-based) carbon pricing creates two related risks. First, it places the energy-intensive industries of the nation pricing carbon at a competitive disadvantage, relative to those of nations lacking policies to reduce emissions. Second, it may encourage “carbon leakage” (exit of energy-intensive activities to such countries), reducing the effectiveness of efforts to limit global CO2 emissions.

Border adjustments (BAs) — pricing carbon embedded in non-fuel imports and rebating carbon prices embedded in non-fuel exports — have been suggested as a means of overcoming these problems. BAs would convert origin-based carbon prices to destination- or consumption-based prices. All nations that employ the VAT provide BAs for their VATs, creating destination-based taxation. In that context BAs are called border tax adjustments (BTAs). In what follows, the term BA refers generically to border adjustments for any form of carbon price; BTAs is reserved for BAs for taxes.

The design and implementation of BAs for carbon prices is extremely complicated. This is especially true if an effort is made to reflect the carbon content of inputs to exports, as well as carbon added at the export stage. For imports the problem is simply that the carbon content of products cannot be observed from their physical appearance and cannot easily be estimated. Whereas most advocates of BAs for carbon prices probably assume, perhaps implicitly, that ad hoc methods would be used to calculate BAs, Courchene and Allan suggest that a CAT with BTAs on carbon embedded in traded products resembling those for the VAT would offer an attractive alternative.

It is also unclear whether the World Trade Organization (WTO) would find BAs for carbon prices are consistent with the rules that govern international trade, primarily the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM). A ruling that they are not would eliminate the case for the CAT. Courchene and Allan suggest, with no supporting analysis, that the BTAs associated with the CAT would be “GATT-legal” — shorthand used here to describe compatibility with the GATT and the ASCM. Also, they do not consider limitations that the WTO might place on the methodologies used to calculate BAs for carbon prices, even if it did not declare them illegal.

This article questions the case for the CAT. First, at the most basic level, it argues that because the carbon content of products cannot be observed, the CAT could not truly function like the VAT and it therefore could not be employed to implement BTAs for imports.

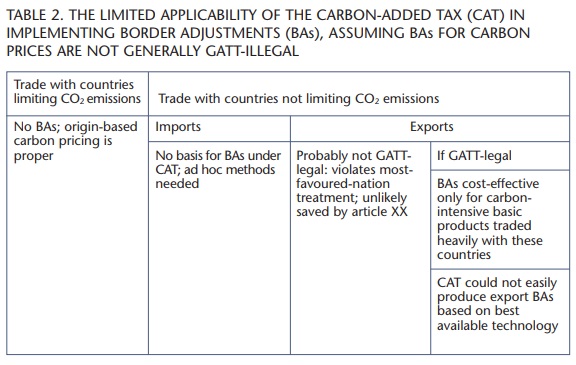

Second, BAs should not be applied to trade with other countries that limit carbon emissions; they should be limited to trade with countries that do not limit emissions. Thus limited, BAs — especially those for exports — may not be GATT-legal.

Third, even if the WTO were to find BAs for carbon prices GATT-legal, it might limit them to carbon content calculated using best available technology or (in the case of imports) the predominant method of production in the importing country. Such a limitation would further undermine the case for the CAT and complicate the calculation of BTAs for the CAT.

The design and implementation of BAs for carbon prices is extremely complicated. This is especially true if an effort is made to reflect the carbon content of inputs to exports, as well as carbon added at the export stage. For imports the problem is simply that the carbon content of products cannot be observed from their physical appearance and cannot easily be estimated.

Finally, it is generally agreed that, for administrative reasons, BAs for carbon prices should be limited to a relatively small number of carbon-intensive basic products.

Because of all these limitations, it would not be cost-effective, even if feasible, to require firms in all sectors to comply with the CAT — or for a government to administer it. In short, the CAT “won’t hunt.” (In the 1960s US President Lyndon Johnson popularized the old southern saying “That dog won’t hunt,” meaning that an idea is not a good one and will not work.) Upstream taxation of carbon is preferable, despite requiring the use of ad hoc methods to calculate and administer BTAs.

It must be admitted at the outset that ad hoc methods would share some (but not all) of the problems identified here. The point is simply that the CAT is not a “silver bullet” that can slay the BA dragon.

It may be useful to note before continuing that, in my correspondence with him, Courchene says that the CAT “is a conceptual framework” that I ignore. But the examples he gives (trade neutrality and avoidance of competitive risk, preference for assignment of emissions to the consuming country instead of the country of origin, taxation of emissions from shipping and preference for destination-based treatment of carbon embedded in interprovincial trade in Canada) are arguments for BAs for carbon prices, not for the CAT, per se. Moreover, Courchene and Allan’s statement that “the devil clearly is in the implementation details (and in particular the details relating to the carbon tariff)” makes it clear that these authors do not intend that the CAT be merely a conceptual exercise; they intend the CAT to be implemented. Implementation is the topic of this article.

BTAs for the CAT cannot be implemented in the same way as those for the VAT.

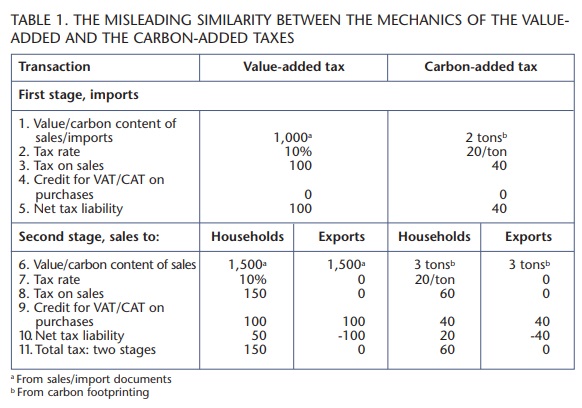

The CAT’s fatal flaw. In calculating liability of the VAT, a trader multiplies sales times the tax rate to arrive at gross tax liability. Net liability is calculated by subtracting (taking input credit for) VAT paid on purchased inputs other than labour, as shown on invoices. Courchene and Allan suggest that liability for the CAT could be calculated in the same way, by multiplying the carbon content of sales times the tax rate and allowing credit for CAT paid on purchases (see table 1). The trouble with this methodology is that, unlike the value of sales used to calculate VAT, the carbon content of products cannot be observed, by either the taxpayer or the fiscal authorities. It would be necessary either to utilize calculations of the carbon content of sales made outside the tax system for other reasons (e.g., to help consumers make informed decisions regarding the environmental impact of their choices) or to specify in the tax system the rules for making such calculations, something that would be far from simple. Neither of these options is attractive, especially given the availability of superior upstream methods of taxing carbon and the limited scope of cost-effective BAs for carbon prices, discussed further below.

Simpler alternatives: domestic carbon added. Except in the case of process-related emissions, such as those from the production of cement, discussed in the next paragraph, the only way to add carbon is to combust fossil fuels. It would thus be much simpler just to tax purchases (or sales) of fossil fuels (including imported fuels) than to implement the CAT. But it would be even simpler to adopt an upstream tax (supplemented with taxation of fuel imports and exemption from, and rebate of, tax on fuel exports), as such a tax would cover all possible purchases of fuel for domestic use. In either case, ad hoc measures would be needed to provide BTAs for nonfuel imports and exports.

Qualifications: where carbon in does not equal CO2 out. Although it is generally satisfactory to assume a close relationship between the amount of carbon purchased and the amount CO2 emitted, this is not always the case. Certain processes can emit CO2 not related to combustion of fuels. It would thus be necessary to supplement an upstream tax on fossil fuels with a tax on process-related emissions. But it would not be necessary or cost-effective to utilize the full CAT methodology for this purpose or to extend it to other sectors.

Moreover, that fossil fuel is purchased does not necessarily mean that CO2 is emitted. Some carbon is physically incorporated in products such as asphalt, steel and tires, and some CO2 may be captured and stored. In theory the CAT could reflect this, whereas simply taxing fuel would not. But offsets could be provided, without adopting the CAT methodology. Carbon capture and storage (CCS), emphasized in Courchene’s correspondence with the author, is likely to make a real difference only in electric generation, plus a few energy-intensive basic industries that combust fuel, rather than relying on electric power, as the production of aluminum does — precisely the same sectors for which ad hoc BAs would be most cost-effective. It would not be cost-effective to impose an economy-wide CAT, merely to reflect the relatively limited effects of CCS; more targeted methods of reflecting CCS would be appropriate.

BTAs for non-fuel exports: the best case scenario. Under the VAT it is simple to eliminate tax on exports. Exports are “zero-rated” (taxed, but at a zero rate) and, as in the case of taxed domestic sales, credit is allowed for tax paid on purchased inputs, and refunded, if net liability is negative. The same technique could, in principle, be used to implement export BTAs for a CAT. This is the

CAT’s primary administrative advantage. But, as explained in the next section, this theoretical advantage may be more apparent than real.

Because of all these limitations, it would not be cost-effective, even if feasible, to require firms in all sectors to comply with the CAT — or for a government to administer it. In short, the CAT “won’t hunt.” (In the 1960s US President Lyndon Johnson popularized the old southern saying “That dog won’t hunt,” meaning that an idea is not a good one and will not work.)

The unknown carbon content of nonfuel imports: Even if the CAT could be used to implement BTAs for exports, the same is not true for import BTAs, which would ideally be based on the carbon added in the foreign countries where imports originate. It is true that the VAT on imports is also levied on something that occurs abroad: the creation of value. But the value of imports is observable, whereas their carbon content is not. (Ad hoc methods share this problem.)

In the case of the VAT it does not ultimately matter whether imports by VAT-registered traders are valued accurately and fully taxed at the border; failure to tax them fully will subsequently be reflected in concomitantly lower input credits. While the same is true in a formal sense in the case of the CAT, the practical difference is striking. Whereas the value of post-import sales is observable, their carbon content is not. If imports are undertaxed at the border because their carbon content is understated and that understatement is reflected in the calculation of post-import carbon footprints, the undertaxation of imports would not wash out, as it does in the case of the VAT. As a result, CAT paid on imports will not equal the CAT levied on local products (assuming, of course, that their carbon content can be accurately determined). Avoiding this would require that calculations of post-import carbon content not be based on the carbon content taxed at the border, something that is possible, but not inevitable.

It is quite possible that the WTO would not approve of any BAs for carbon prices. (Courchene and Allan state that, because the CAT functions like the VAT, it should be GATT-legal. This opinion appears to be based on economic reasoning, rather than a careful reading of the GATT, the ASCM, cases interpreting them or literature commenting thereon.) If BAs for carbon prices were found not to be GATT-legal, the case for the CAT would evaporate, as it relies entirely on the suggestion that it would facilitate BTAs. (See the previous discussion of simpler alternatives.)

The key issue is whether domestic carbon prices and BAs on imports are imposed on “like products.” If carbon prices are found not to be imposed on products, BAs for them are not GATTlegal. Beyond that, if carbon-intensive imports and physically identical “clean” domestic products are deemed to be “like,” BAs that reflect the carbon intensity of the former would not be allowed. (The question is whether differences in “processing and production methods,” as manifested in differences in carbon intensity, make products unlike.) These are complicated issues on which experts do not agree and that cannot be reviewed here; they will not be settled until the WTO decides a concrete case, if then.

BAs based on BAT or PMP: general. The WTO might rule that BAs for carbon prices can be based only on best available technology (BAT) or (in the case of imports) the predominant method of production (PMP). There is no analogous limitation on BTAs for the VAT. Of course, with this limitation, if the actual carbon content of a traded product exceeds that under BAT or (for imports) PMP, the CAT embedded in exports would not be eliminated, and imports would not be taxed as heavily as domestic production. (This is also true of BAs calculated using ad hoc methods.) Contrary to what Courchene and Allan say, destination-based taxation would not be fully achieved.

Implementing export BTAs based on BAT. Implementing export BTAs based on BAT would not be simple. As noted above, zero-rating exports would eliminate CAT, in effect producing BTAs based on the actual carbon content of exports, not on BAT. It would be necessary to modify zero-rating to comply with a BAT limitation on export BAs.

How to do that is not obvious; it probably would not be simple — certainly not as simple as zero-rating and perhaps not as simple as using ad hoc methods to calculate BAs for a limited number of sectors.

Implementing import BTAs based on BAT or PMP: If import BAs were to be limited to BAT or PMP, it would not be satisfactory simply to use one of these methodologies to calculate the amount of CAT to impose at the border and then calculate post-import carbon footprints based on the actual carbon content of imports (however that might be done), as that would have the effect of negating the reduction in import BTAs implied by BAT or PMP. Because of the way gross liabilities for the CAT are calculated, it would be necessary to utilize the carbon content of imports calculated under the chosen method (BAT or PMP) in calculating post-import carbon footprints for purposes of the CAT all the way to the retail level. (In this case the kind of undertaxation described above would be consistent with a BAT or PMP limit on import BAs.) Carbon footprints calculated for non-tax reasons are unlikely to be based on BAT or PMP.

A mixed system for pricing carbon. Whether one of a nation’s trading partners employs an origin-principle VAT a destination-based VAT, or no VAT at all does not affect the choice of whether to make BTAs for the VAT on trade with that country. (As a practical matter, virtually all VATs are destination-based.) The same is not true of the CAT. It would be inappropriate — and probably not GATT-legal — to apply BTAs to trade with countries that price carbon on an origin basis (or that utilize similarly effective origin-based non-price means of reducing emissions), as that would result in no carbon pricing of exports and double carbon pricing of imports (or their economic equivalents), a highly distortionary result that could not be justified by the raison d’être of carbon prices. (Origin-based systems are the only ones currently in use and the only ones likely to be used, aside from mixed systems. The European Emission Trading System is the best extant example of an origin-based system.) BAs for carbon prices should be applied only to trade with countries that do not price carbon (or otherwise reduce emissions), producing a mixed system. That is, only exports to such countries should be zero-rated and only the carbon content of imports from them should be priced. There is nothing analogous under the VAT.

The GATT-legality of export BTAs in a mixed system. However the general issue of GATT-legality is resolved, BTAs for a CAT — or indeed BAs for any carbon price — levied in the context of a mixed system might not pass muster under the GATT. A mixed system would clearly violate the most-favoured-nation provision, which prohibits differential treatment of trade with different members of the WTO. It would be necessary to seek an exception under article XX of the GATT. It is unknown whether, but perhaps not unlikely that, import BAs would be allowed under paragraph (g) of that article, which allows exceptions for measures “relating to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources if such measures are made effective in conjunction with restrictions on domestic production or consumption.” But it is difficult to argue that export BAs further this objective, as they allow domestic producers to avoid the carbon price intended to reduce CO2 emissions by exporting. Since, as argued above, the CAT does not facilitate import BTAs, this more limited decision would, by itself, eliminate the case for the CAT.

Research suggests that a carbon price would increase production costs significantly for only about 1 percent of economic activity, including aluminum, iron and steel, wood and paper, cement and lime, and chemicals, in addition to petroleum products. (The list may include more or fewer industries in some countries.) It is thus generally agreed that, for administrative reasons, BAs should be limited to a few carbon- and trade-intensive basic industries, as these are the ones where potential loss of competitiveness and carbon leakage are greatest. Under a mixed system BAs should be even more limited — to trade of those sectors with countries that do not have equivalent measures to reduce CO2 emissions. Table 2 summarizes these limits. It would not make sense to create a complex economy-wide CAT system simply to provide BTAs for this limited portion of international trade. This conclusion is enforced by the fact that embedded carbon does not constitute much of the value of most finished products — and, of course, by the availability of the much simpler system for taxing carbon described in this article.

The CAT would entail high costs of compliance and administration and might produce little benefit. It would not be cost-effective to introduce it simply to implement BTAs, even if it were GATT-legal and could achieve that objective, which is not the case for imports. The most efficient way to implement a carbon tax is to impose it upstream. It is true that an upstream carbon tax would not provide the information required to calculate BTAs; it should be necessary to calculate BTAs in some other ad hoc way. But that is also true of BTAs on imports under the CAT. Fortunately, BAs would be needed for trade only in a limited number of carbon-intensive basic products that are traded heavily with countries that do not limit CO2 emissions.

Photo: Shutterstock