Creating sustainable value is our 21st-century challenge. Canadians have long relied on governments and community organizations to meet evolving social needs, while leaving markets, private capital and the business sector to seek and deliver financial returns. However, this binary system is breaking down as profound societal challenges require us to find new ways to fully mobilize our ingenuity and resources in the search for effective, long-term solutions.

Jolted by economic shocks and under increasing social and environmental pressure, the world is recalibrating toward a new normal. In a time of political change and economic bootstrapping, we must explore new approaches to addressing Canada’s most pressing social challenges. To release financial, social and environmental pressure points, governments can catalyze the creation of “social” or cross-sectoral partnerships with the private, philanthropic and community sectors. Elected representatives will find allies in these communities to support and deliver the innovative solutions required in this remarkable period in human history.

Alongside policy leadership in government, the financial and philanthropic sectors are engaged in developing a social finance marketplace to help entrepreneurs and enterprising nonprofits tackle the challenges in our communities and the environment. These challenges demand a new approach from funders — one in which our investments deliver more than financial returns, precisely because we select these investments thoughtfully and deliberately to also make a positive contribution to society or to the health of our planet.

Federal, provincial and regional governments can also support new funding strategies to complement existing grants and contributions and leverage private capital for social enterprise. A burgeoning number of innovative enterprises tackling social issues are finding it very difficult to secure risk capital to support their growth and maximize their impact. A recent study by the Social Venture Exchange, involving 270 social ventures in Ontario, highlighted $170 million in capital demand, with 70 percent of the ventures reporting capital access as a major barrier to their success. At the national level, we can expect this figure to be between $450 million and $1.4 billion.

In December 2010 the Canadian Task Force on Social Finance released its report, Mobilizing Private Capital for Public Good, announcing seven highly targeted and practical recommendations to develop a social finance marketplace in this country. Canada is now at a watershed in the development of a thriving social financial sector.

The task force defined the terms “social finance” and “impact investing” as “actively placing capital in businesses and/or enterprising charities and non-profits, and funds that generate social and/or environmental good and (at least) a nominal principal to the investor.” Impact investors are those who “seek to harness market mechanisms to create social or environmental impact.”

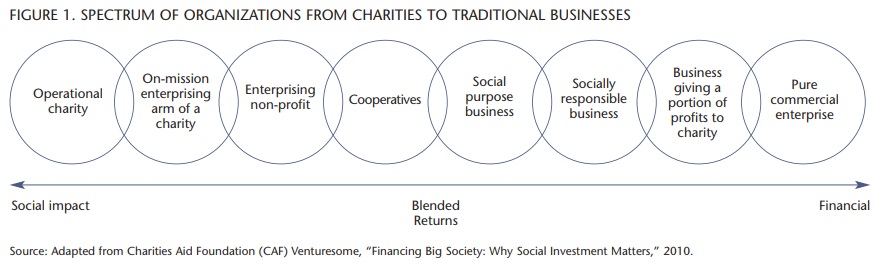

Our focus here is on catalyzing “social enterprises,” a term that refers to a range of market-oriented organizations pursuing public benefit missions, including enterprising charities and nonprofits, cooperatives and for-profit social purpose businesses. Figure 1 illustrates the spectrum of social enterprises, and their positioning relative to organizations driven primarily by social impact and those driven primarily by financial returns.

The reasons why social finance is important are inextricably tied to the need to bolster “social innovation.” By this, I mean developing initiatives, products or processes that profoundly change the routines, resources and beliefs of social systems. Social innovation represents a fundamental shift in the allocation of value — in a way that builds greater social and ecological resilience. Canada’s ability to conceive, build and scale social innovations will require more capital than is available through philanthropy and government. Canada’s emerging social finance marketplace will allow public and philanthropic capital to leverage significantly more private capital to achieve long-term benefits for Canadians.

The task force was convened by Social Innovation Generation (SiG), a national partnership of the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation, the PLAN Institute in Vancouver, the University of Waterloo and MaRS Discovery District in Toronto. SiG aims to foster a culture of continuous social innovation, helping practitioners across Canada address large-scale complex challenges as diverse as climate change, aging, sustainable food production and social inclusion. To make progress on these issues, we need to leverage the creativity and competencies of the private sector, government, community organizations and our entrepreneurs, and put in place the financial resources to support their efforts.

Canada’s ability to conceive, build and scale social innovations will require more capital than is available through philanthropy and government. Canada’s emerging social finance marketplace will allow public and philanthropic capital to leverage significantly more private capital to achieve long-term benefits for Canadians.

In the past, government has provided much of the impetus for societal progress, with innovations such as universal health care and public education systems redefining what was possible in their time. Government has also been a major funder of the community organizations grappling head-on with social issues. This role is being overstretched.

Canada, like many nations, will face a major fiscal challenge in coming years. Demographic changes and the global financial crisis are striking parallel blows to government budgets, which will increase the pressure on social services while reducing the tax base available to fund them. Canada currently faces a $40 billions federal deficit, and among the provinces, Ontario, for example, forecasts it will have a deficit of over $16 billion for 2011. Spending cuts are a foregone conclusion, and traditionally grant-funded charities or nonprofits cannot expect to be spared.

Beyond this trend, many argue that the prevailing system of funding charities and nonprofits is already in decline. Tim Brodhead, CEO of the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation and a member of the Canadian Task Force on Social Finance, has argued that traditional fundraising models starve the community sector of the resources required to scale their impact. Grant and donation income is often short-term and does not support long-term staff development or organizational sustainability. In addition, constant fundraising pressures distract organizations from their core missions. A paycheque-to-paycheque mode of operating limits the appetite for innovation and growth.

On this shifting landscape, the traditional distinction between the private and social sectors is increasingly blurred. A leading voice in this dialogue is Harvard University professor and noted business author Michael Porter, who describes the potential for the private sector to play a key role in creating “shared value,” described as “economic value…that also creates value for society by addressing its needs and challenges.” Companies that embrace this potential are re-envisioning their value chains to support smallholder farmers, to develop the next generation of clean technology products and to invest in building successful businesses in distressed neighbourhoods. They are moving beyond the paradigm where corporate concern for social issues is restricted to charitable giving or corporate social responsibility departments.

Porter builds on the “blended value” framework developed by Jed Emerson and his work is reminiscent of Peter Drucker’s prescient 1986 book The Frontiers

of Management:

Only if business learns how to convert the major social challenges facing developed societies today into novel and profitable business opportunities can we hope to surmount these challenges in the future. Government, the agency looked to in recent decades to solve these problems, cannot be depended on. The demands on government are increasingly outrunning the resources it can realistically hope to raise through taxes. Social needs can be solved only if their solution in itself creates new capital, profits, that can then be tapped to initiate the solution for new social needs.

This movement is in line with the views expressed by Sir Ronald Cohen, chair of the United Kingdom Social Investment Task Force, who claimed in a 2010 speech to Harvard University students that “fundamentally, part of the capitalist system must be a strong social sector that can address social issues because governments do not have the resources,” and that there is “a critical need for sustainable investment in poorer communities if free market societies are to maintain cohesion.” This is not to blame capitalism for intractable social problems, but to recognize that potent resources for tackling critical social issues remain unharnessed in the capital markets.

Social finance practitioners have realized that we now need to create supportive infrastructure and specific instruments that deliberately harness private capital to find resolutions to social problems, resolutions traditionally funded by the state. Judith Rodin, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, has aptly observed that “while there is not enough money in foundation and government coffers to meet the defining tests of our time, there is enough money. It’s just locked up in private investments.” This means that we need to find pathways for individuals, private venture funds, large institutions and philanthropic investors to access “blended” value investments.

Why are social purpose businesses needed? For Paul Martin, the former prime minister and Canadian Task Force on Social Finance member, the answer is clear: “The business entrepreneur improves our quality of life by creating wealth and economic growth. The social entrepreneur improves our quality of life by confronting the inequality that is often the collateral occurrence of free markets,” he said in a 2007 speech to the Munk Centre. “Both kinds of entrepreneurs are necessary. Let us give them both the chance to succeed.”

The type of business activity Martin refers to includes companies that actively employ otherwise marginalized populations in meaningful work. These businesses need funding. However, the process of raising capital remains highly inefficient because the appropriate infrastructure, intermediaries, standards, regulation and incentives do not exist.

From the point of view of investors like Toronto-based Social Capital Partners (SCP), such companies represent opportunities to invest in profitable businesses that improve social cohesion and reduce welfare dependence. They often yield a lower financial return on investment due to higher operating costs, making a clear “social return on investment” crucial for enticing investors. In SCP’s case, this means providing loans with an interest rate that declines in proportion to the number of “social hires” an investee takes on. Pioneering social finance practitioners like SCP are at the forefront of defining the infrastructure and systems that will efficiently connect impact investors with organizations that are doing the work that they want to support, to make a financial return on their investment but also to make a difference in their community.

Many community organizations try to enhance their fiscal sustainability through a variety of earned income models, adopting more marketoriented approaches where appropriate. As asserted in the Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation March 2011 report Strengthening the Third Pillar of the Canadian Union, “charities and non-profits rely on three core sources of revenue: government funding, philanthropy, and earned income. Of these, only earned income offers any prospect for growth over the long-term.”

However, a mix of complicated and restrictive regulations, a lack of internal or external support, and an existing culture of grant making among traditional funders means that generating earned income is far from straightforward. Governments at federal and provincial levels can take immediate action to reform and clarify the applicable regulatory regime and investigate enacting new tax incentives and hybrid corporate models to help address such difficulties.

Beyond this, social finance solutions may include creative mechanisms to allow nonprofits, too often long-term tenants, to collectively or independently buy the buildings they operate in and build assets over time; to finance mission-related activities directly; or to help start and grow profit-making enterprises that support nonprofit organizations and activities. An excellent example of the latter is the Atira Women’s Resource Society in BC, which has “built a highly successful property-management company that now employs 200, many of them former clients, in a successful bid to earn money that pays for the transitional emergency housing it was set up to provide.”

Canada’s philanthropic sector can play a lead role here, both through targeted grant making and by rethinking the manner in which their assets are deployed to directly support innovation in beneficiary organizations. Whereas most foundations continue to invest their endowments in traditional capital markets and grant only the interest earned, many are now seeking opportunities to also make mission-related investments. Loans to nonprofit organizations pursuing earned income strategies can augment the impact of grants and stretch philanthropic dollars further in the face of economic pressure on endowments and flatlining public donations. Compared to many other investors, foundations enjoy relative flexibility, longer time horizons and lower risk sensitivity, so they are well positioned to lead in this emerging field.

Opportunities are also emerging to help channel private capital for direct investment into social service provision. A complex variant is the social impact bond (SIB), currently being piloted in the United Kingdom and proposed in the United States, Australia, British Columbia and Ontario. SIBs are bondlike instruments, purchased by private investors, to finance projects delivered by (public or private) agencies providing social services. Financial returns are paid to investors by government, but only if the program is successful. These returns (often capped) are funded out of the savings in anticipated public spending due to the positive results of the program. SIBs shift risk to private investors and mobilize new capital to help successful programs scale, while freeing up taxpayer funds to be allocated to proactive preventive programs. Potential applications of SIBs in the Canadian context include Aboriginal employment, immigrant settlement, public health programs, disabilities support and demand-side energy management.

SIBs are important for several reasons: They profile a new way to leverage private capital for public good; they place attention on the need for social expenditure to focus on variable impacts, not just outputs; and they offer a way to generate proof-of-concept for new social innovations that might not otherwise get to evidence-based evaluation in the real context of their implementation.

A recent JP Morgan report found that impact investing was potentially worth between $400 billion and $1 trillion globally; on similar calculations, the Canadian number could approach $30 billion. Significant work is being done to establish international standards and a common language for assessing social impact, which will in turn assist with reporting, transparency and comparability.

The social finance movement has gained tremendous momentum in recent years. Canada cannot afford to miss the opportunity that this movement represents for building sustainable value, and it has every opportunity to play a leadership role in its evolution. Key elements of a social finance marketplace have started to firm up in Canada. These include a growing number of investors concerned with social impact, an emerging group of impact investment funds, foundations exploring mission-related investing and an expanding community of vibrant social entrepreneurs.

Social finance solutions may include creative mechanisms to allow nonprofits, too often long-term tenants, to collectively or independently buy the buildings they operate in and build assets over time; to finance mission-related activities directly; or to help start and grow profit-making enterprises that support nonprofit organizations and activities.

Recognizing the opportunities, SiG convened an initiative in 2007 to help the Canadian social finance movement find its unified voice. This three-year project aimed to fast-track Canada’s adoption of social finance, ensuring that there is a healthy marketplace, supported by mainstream financial institutions, serving a national constituency of social purpose businesses, charities, social enterprises, social economy entities, community economic development institutions and cooperatives.

The convening of the Canadian Task Force on Social Finance was a critical step in this process. The independent task force consisted of business, public policy and philanthropic leaders from across the country, and its mandate focused specifically on identifying ways to mobilize private capital for public good, thereby creating an opportunity for social entrepreneurs to “fundamentally change the way we think about — and solve — societal challenges.” The work of the task force built on a strong foundation of research, benchmarking national initiatives against international experience and best practices.

The task force took many cues from its UK predecessor, the Social Investment Task Force. With the recent release of its fourth and final report, this group concluded a decade of experimentation, during which it demonstrated an impressive record of influencing government policy and private sector investment in a new breed of funds and social enterprises. Drawing on this experience, the Canadian task force report represents a road map for unified action to build the sector in Canada.

The Canadian task force made seven interdependent recommendations, which represent an “integrated national strategy” to mobilize new sources of capital, create an enabling tax and regulatory environment, and build a pipeline of investment-ready social enterprises. Many recommendations focus on government policy; however, financial institutions, investors, philanthropists and other community organizations all have an important role to play.

Implementation of the recommendations outlined in the report will build capacity in Canada’s emerging social finance marketplace and allow public and philanthropic capital to leverage significantly more private investment to achieve long-term benefits for Canadians.

Four of the seven recommendations aim to increase the flow of capital into the social finance sector. The roles of government, public and private foundations, institutions and pension funds were particularly highlighted here among a broader class of actors. These are the seven recommendations.

(1) To maximize their impact in fulfilling their mission, Canada’s public and private foundations should invest at least 10% of their capital in mission-related investments (MRI) by 2020 and report annually to the public on their activity.

(2) To mobilize new capital for impact investing in Canada, the federal government should partner with private, institutional and philanthropic investors to establish the Canada Impact Investment Fund. This fund would support existing regional funds to reach scale and catalyze the formation of new funds. Provincial governments should also create Impact Investment Funds where these do not currently exist.

(3) To channel private capital into effective social and environmental interventions, investors, intermediaries, social enterprises and policy makers should work together to develop new bond and bond-like instruments. This could require regulatory change to allow the issuing of certain new instruments and government incentives to kick-start the flow of private capital.

(4) To explore the opportunity of mobilizing the assets of pension funds in support of impact investing, Canada’s federal and provincial governments are encouraged to mandate pension funds to disclose responsible investing practices, clarify fiduciary duty in this respect and provide incentives to mitigate perceived investment risk.

(5) To ensure charities and nonprofits are positioned to undertake revenue generating activities in support of their missions, regulators and policy makers need to modernize their frameworks. Policy makers should also explore the need for new hybrid corporate forms for social enterprises.

(6) To encourage private investors to provide lower-cost and patient capital that social enterprises need to maximize their social and environmental impact, a Tax Working Group should be established. This federal-provincial, private-public Working Group should develop and adapt proven tax-incentive models, including the three identified by this Task Force. This initiative should be accomplished for inclusion in 2012 federal and provincial budgets.

(7) To strengthen the business capabilities of charities, non-profits and other forms of social enterprises, the eligibility criteria of government sponsored business development programs targeting small and medium enterprises should be expanded to explicitly include the range of social enterprises.

The report of the Social Finance Task Force was launched at a meeting of 400 sector leaders at the MaRS Discovery District in December 2010, with the strong endorsement of many global social finance leaders. Investors, foundations, government and social entrepreneurs have already begun to embrace the task force’s recommendations. For example, Philanthropic Foundations Canada, Community Foundations of Canada (CFC) and the Canadian Environmental Grant Makers Network are holding national workshops on the first recommendation on mission-related investments, on which the CFC has already encouraged its 178 members to act.

In December, Finance Minister Jim Flaherty distributed the report to his provincial and territorial counterparts and their deputy ministers, and multiple federal departments have begun exploring social finance approaches. The government of British Columbia has formed an external Advisory Council for Social Entrepreneurship, reporting to the BC parliamentary secretary for nonprofit partnerships, and the Nova Scotia government has for the first time incorporated social enterprise in its provincial economic strategy. Representatives from banks, mutual fund companies and credit unions interested in implementing the recommendations have approached task force members and are pursuing new product opportunities for retail investors.

On March 22, 2011, the proposed federal budget cited the task force and spoke of pending initiatives relating to its recommendations.

The task force’s goal was to raise awareness of social finance and stimulate a national discussion about a new partnership model between profit and public good. The task force will produce a progress report at the end of 2011, and given the activity already under way, I am confident that it will exceed expectations.

Social finance solutions may include creative mechanisms to allow nonprofits, too often long-term tenants, to collectively or independently buy the buildings they operate in and build assets over time; to finance mission-related activities directly; or to help start and grow profit-making enterprises that support nonprofit organizations and activities.

When the task force started its work, it set out to play a catalytic role in raising awareness about social finance and accelerating its development in Canada. The report’s seven recommendations are a starting point. It continues to look to innovation brokers and convenors, such as MaRS Discovery District, the Public Policy Forum and SiG, to facilitate consultations with the various sectors implicated in the report, and for key actors to assume leadership roles in developing implementation strategies.

The private sector needs to engage and lead the creation of new pools of capital and develop approaches to employing that capital in the most sustainable and financially effective manner. Mainstream financial institutions can bring their considerable expertise to bear on designing appropriate mechanisms and instruments, while entrepreneurial wealth advisers and groups can develop retail-oriented impact investment products to meet growing interest in that sector. Institutional investors such as pension funds can work proactively with government and foundations to responsibly invest a modest portion of their assets for the betterment of the communities in which those assets are generated. Foundations can move more aggressively to begin making missionrelated investments, putting more of their asset base to work to augment their social mission, and philanthropic funders in general can actively support leading innovators and sector builders. Community organizations and social purpose entrepreneurs must continue to innovate and collaborate with a variety of partners that can support the implementation of their ideas. As training, support and financing opportunities develop, they must remain vocal and engaged, as their practical experiences are invaluable for identifying best practices.

Governments, federal and provincial, can review and work to implement the regulatory and tax reforms identified, convene working groups to inform broader changes, and seek partnerships with the private sector to create new pools of capital and grow the funds that already exist to do more.

In Strengthening the Third Pillar of the Canadian Union, the Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation outlined an intergovernmental agenda for Canada’s charities and nonprofits. The report lays out a compelling vision for greater jurisdictional clarity around the regulation and governance of the community sector.

“Provincial governments, with Ontario and British Columbia at the forefront, are paying greater attention to their jurisdictional responsibilities with respect to the sector and, in some cases, are beginning to modernize policy and regulatory frameworks that are now decades out of date.

At the same time, federal, provincial and territorial governments are looking more seriously at the opportunities offered by social enterprise and social finance, with a view to opening up new sources of financing for public benefit initiatives and programs, and containing the growing fiscal pressure.

The provinces have constitutional responsibility over charitable and provincially incorporated nonprofit entities, while the federal government has authority over their taxation benefits under the Income Tax Act. Under this confusing arrangement, the Canada Revenue Agency’s regulatory activity and the federal Income Tax Act are proving a barrier to many of the activities that some provinces are trying to nurture.

Overlapping federal and provincial responsibilities and barriers are commonplace in Canada, but in response, governments have established processes where ministers and public servants meet to coordinate their activities and reduce the number of overlapping and conflicting regulations.

No such effort exists with respect to the nonprofit sector.

The private sector needs to engage and lead the creation of new pools of capital and develop approaches to employing that capital in the most sustainable and financially effective manner.

The problem our federal, provincial and territorial governments face is how to find and implement solutions to current regulatory and policy challenges in the absence of any shared table or process through which to sort out what must be done.”

We endorse the Mowat Centre proposal that the federal, provincial and territorial governments “establish a formal FPT [federal, provincial and territorial] process to address non-profit sector issues and challenges, giving particular attention to the pressing issue of sustainability.” The time has arrived for nongovernment players to take the lead in convening such a meeting. Borrowing from leading businesses that engage customers directly in product innovation, Canada could, by adopting a “cocreation” approach whereby governments directly engage citizens and stakeholders in generating solutions, set a new standard for developing more relevant and effective 21stcentury policies and programs.

We face challenges of such a scale that we owe it to future Canadians to urgently move this agenda forward. It offers us the opportunity to forge new partnerships between government, business and the community sector that align our respective strengths and our shared aspirations for the future of this remarkable country. I have every expectation that we are up to the challenge.

Photo: Shutterstock