All is far from well on the federal-provincial fiscal arrangements front. The equalization-receiving provinces are concerned that the combination of a fixed equalization pool (albeit escalating annually), on the one hand, and the reality that populous Ontario has joined the have-not provinces, on the other, will significantly reduce the value of their equalization payments. Drawing on analysis from Winnipeg’s Frontier Centre for Public Policy, Alberta spokespersons have aired the concern that Canada’s system of federal-provincial transfers is over-equalizing, with the result that the poorer provinces are able to deliver enhanced levels of public services than can some richer provinces (e.g., higher teacher-student ratios, more physicians and nurses per capita). In other quarters there is concern, thanks to Paul Martin’s 2004 10-year accords, that health transfers are growing by 6 percent annually, while inflation is only in the 2 percent range, and that the equalization pool is increasing annually (currently at the growth rate of nominal GDP), irrespective of the likelihood that interprovincial fiscal disparities have, for the most part, been decreasing.

And all of this without recognizing that the elephant in the room — carbon pricing and the resulting revenue allocation between Ottawa and the provinces — may be about to stir. Peter Lougheed may yet be proved correct when he suggested that the federal-provincial and interprovincial struggle over the revenues arising from carbon pricing may well overshadow the National Energy Program donnybrook.

For these and other reasons it seems appropriate, as part of the federal-provincial relations theme of this issue, to provide a historical overview of the evolution of and rationale for Canada’s system of federal-provincial financial relations.

Arguably, the most appropriate starting point is the introduction of Quebec’s 15 percent personal income tax (PIT) in 1954. The trigger for this action was the attempt by Ottawa in 1951 to transfer monies directly to the universities, i.e., bypassing the provinces. Not surprisingly, Premier Maurice Duplessis viewed this as an unwanted intrusion in an area of Quebec’s exclusive jurisdiction, an intrusion made possible in large measure by Ottawa’s superior access to revenues. In order to counter this, Quebec realized that it also needed additional revenue sources. Hence its introduction of the PIT and that tax’s role as the symbol of provincial autonomy, created as much as a bulwark against the exercise of the federal spending power as an instrument to generate revenues, per se.

However, the implications of the Quebec PIT turned out to be both dramatic and far reaching. The first of these was the decision by the federal government, as part of the 1957 Tax Sharing Agreements, to offer all the provinces the option of levying their own taxes (or receiving an abatement or reduction in federal tax) equal to 10 percent of the federal PIT, 9 percent of the federal corporate income tax (CIT), and 50 percent of succession duties, with the federal government agreeing to collect the provincial taxes free of charge. Because these provincial revenues from piggybacking on federal taxes were to be allocated across provinces on the basis of the derivation principle (i.e., on the basis of what was actually raised in each province), they generated very different per capita revenues across provinces.

This led to a second key implication of the Quebec PIT: in order to compensate for these per capita differences in this federal move toward tax sharing, Ottawa inaugurated Canada’s formal equalization program, also as part of the 1957 quinquennial reworking of the fiscal arrangements. This initial program equalized the revenues from the PIT, CIT and succession duties to the average of the top two provinces (Ontario and British Columbia, with Ontario emerging as the only nonequalization-receiving province). Hence, Canada’s formal equalization program clearly finds its origins and rationale in accommodating the Quebec PIT. While equalization is typically viewed as benefiting only the receiving provinces, a case can be made that equalization also benefits the rich provinces. This is so because, without an equalization program in place, Ottawa would not have ended up transferring anywhere near as much in the way of tax room to the provinces that it eventually did. More to the point, the traditional have-not provinces would have stood in the way.

All of this without recognizing that the elephant in the room — carbon pricing and the resulting revenue allocation between Ottawa and the provinces — may be about to stir. Peter Lougheed may yet be proved correct when he suggested that the federal-provincial and interprovincial struggle over the revenues arising from carbon pricing may well overshadow the National Energy Program donnybrook.

A third and truly transformative implication arising from the above analysis draws from the writings of Claude Forget. He points out that, prior to the Quebec PIT, if the provinces wanted a new program in an area of exclusive provincial jurisdiction, the obvious route was to amend the constitution and transfer this power to Ottawa. This was what occurred for unemployment insurance in 1940 and for old age pensions in 1951. However, the key spending programs that came after the Quebec PIT and the above-noted associated developments, namely hospital insurance, medicare, post-secondary education and social assistance, were provincially administered programs with federal cost sharing. Moreover, while the cost sharing initially took the form of conditional grants, these eventually became unconditional and, to a considerable degree, were replaced by additional transfers from Ottawa to the provinces in the form of equalized personal income tax points.

Thus the shift from federally funded, federally regulated/administered programs to shared cost programs under provincial design and administration, and finally to autonomous provincial programs funded by effectively unconditional grants and equalized tax-point transfers is not only a model for decentralized federations everywhere, but is witness to the creative ability that Canadians and their governments can bring to the governance of our federation.

At this juncture several further observations are in order. First, suppose that a federal country operates a progressive income tax and uses the proceeds to provide expenditures that are roughly equal per capita. While similarly situated citizens (e.g., same income, same family composition) will pay identical amounts of taxes no matter where they reside, it will nonetheless be the case that provinces with higher-income residents will find that their residents (but not the provinces themselves) are paying more to Ottawa than they are receiving from the equal per capita expenditures. This is the inevitable and appropriate consequence of the operations of an income tax system, progressive or even proportional. I would hazard a guess that it is this natural operation of the PIT (and CIT, etc.) that accounts for much to the “excess contribution” that Ontario (earlier) and Alberta (now) claim that they are making to the financing of the federation. Yet, the reality is that individual Albertans and Ontarians are treated identically to similarly situated Nova Scotians. A related observation is that no province ever transfers any of its ownsource revenues to Ottawa or to its sister provinces, although one often hears comments from various quarters that seem to imply this.

Now that the funding of equalization has been broached, a third observation is in order. Because the revenues subject to equalization in the 1957 version of equalization (PIT, CIT and succession duties) were shared with Ottawa, there was complete congruence between the provincial source of any increase in equalization and the provincial source of Ottawa’s revenues needed to finance this increase. For example, if the increase in equalization is occurring because income taxes are rising in the rich provinces, Ottawa’s income taxes from residents in these same provinces must, by the definition of shared taxes, also be increasing. It was this convenient congruence that came to an abrupt end with, first, the introduction of the 1967 comprehensive equalization system, which equalized all provincial revenues (classified into 30-odd tax bases, including roughly a dozen energy and resource bases) to the national average standard (NAS) and, second, the two energy shocks (the 1973-74 OPEC hike and the 1979-80 Iraq-Iran War).

In the face of the resulting dramatic upward spikes in energy prices, had Ottawa allowed domestic oil prices to go to world levels, the reality would have been not only that Ontario would become a have-not province but, thereafter, every additional dollar of oil revenue accruing to the energy provinces would have increased federal equalization payments by 75 cents. This is clear from the NAS formula, where the equalization payments arising from oil revenues for each province can be expressed as follows: equalization for oil = total oil revenues (% population – % tax base). Given that Ontario has about 37 percent of the population and zero percent of the oil base, Ontario equalization alone would be 37 cents on any additional dollar of oil royalties which, when combined with those of other have-not provinces with a low or zero oil tax, brought the total to the above noted 75 cents. More concretely, the calculations for 1981-82 indicated that continuing with the then-existing equalization formula would have increased equalization by $3 billion — from $4.6 billion to $7.6 billion. Since Ottawa cannot constitutionally get access to any energy royalties accruing to the provinces, this meant that Ontario’s residents would contribute roughly 40 percent of this additional $3 billion in equalization, whereas Albertans would contribute about 12 percent, these percentages reflecting the provincial shares of Ottawa’s revenues. The projections at the time were that federal income tax revenues would have to increase by 25 percent.

Clearly, Ottawa was not about to let this scenario play out. Rather, Ottawa embarked on a dizzying array of defensive and all-too-often controversial initiatives: pegging the domestic energy price well below the world price; implementing an export tax on oil equal to the difference between the global and the domestic price; disallowing the deduction of provincial royalty payments for the federal CIT; reducing the amount of energy royalties that could enter the equalization formula; and retroactively disqualifying Ontario from receiving equalization, even though it was a have-not province, for each year between 1977 and 1982, among many others. This last initiative was accomplished via the “personal income override”: a province could not receive equalization if its per capita personal income was above the national average. While this was cast in general terms, the only province affected was Ontario.

And all of these were a prelude to the infamous National Energy Program (NEP) in the fall of 1980, which was a broadside against the energy patch and especially Alberta, and which remains permanently etched in the psyche of Albertans. Among its provisions were a federal tax on natural gas sales; an 8 percent tax on corporate resource royalties; a charge to promote Canadian ownership in the oil sector; the Petroleum Incentive Program (PIP) grants to explore in “Canada Lands” rather than in “province lands”; and the “back-in” provision, whereby Ottawa reserved a 25 percent interest in all existing and future petroleum rights on Canada Lands. While the NEP was appropriately viewed as a political and constitutional affront to the western energy provinces, it was not, of and by itself, the fiscal disaster that it is commonly assumed to have been.

There are two prongs to this claim. The first is that the revenues diverted or appropriated from Alberta by the series of initiatives prior to the NEP were arguably much larger than the actual fiscal damage arising from the NEP itself. For example, in 1979-80 the made-in-Canada oil price was $20 per barrel below the world price, the result of which was that the foregone provincial energy revenues were, at unchanged production levels, $7 billion per year. Another perspective is that by 1980 the province of Alberta had already “subsidized” Canadian consumers (via lower domestic oil prices) to the extent of some $30 billion. The second prong relates to the post-NEP period. Ottawa’s 1981 series of NEP compromises with Alberta included a commitment to allow the domestic price to rise to $60 per barrel instead of the $40 ceiling under the NEP. This would have led to very significant revenues for Alberta and, more generally, the western energy provinces, were it not for the reality that by 1986 the world price had collapsed to $20 per barrel, dragging the Canadian price down with it. Ever since then, domestic and world prices have moved in lock-step. In other words, it was the global energy price collapse, not the NEP per se, that led to the depressed fiscal fortunes of the Alberta economy in the mid-to-late 1980s and to its qualifying for federal stabilization payments.

However, the longer-term political/constitutional ramifications of the NEP proved to be most significant. In order to bring Alberta and the energy provinces onside in the 1980-82 constitutional negotiations, Ottawa introduced s.92A into the Constitution Act 1982. In effect, this gave the provinces control over the exploration, development, management, conservation and any means of taxation, in respect of nonrenewable natural resources, forestry and the generation of electricity. Among other implications, this new constitutional provision bolsters the various provincial attempts to implement carbon pricing, the revenues from which may well rival those associated with energy royalties themselves.

As already noted, former Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed has recently warned Canadians that the intergovernmental political and financial stakes are so high in this area of “environmental federalism” that we may be marching toward a crisis that could even overshadow the NEP. And in terms of the NEP itself, Premier Lougheed, before leaving office in 1985, brought Alberta fully onside with the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiations launched in 1986, because its provisions virtually guaranteed that Ottawa could never repeat the NEP: “the FTA is our auto pact,” was his response to Ontario and Ontarians who were against the FTA.

Meanwhile, much was also afoot on the fiscal arrangements front. The 1977 arrangements led to the blockfunding of the so-called “established programs” (federal-provincial cash transfers for hospital, medical and postsecondary education expenditures), with the transfers for welfare continuing with their 50-50 tax-sharing format.

Part of the rationale for replacing these heretofore open-ended 50-50 sharedcost programs was that federal expenditures on them were beyond Ottawa’s control: they were determined by the collective decisions made in the provincial capitals. Henceforth these transfers would be unconditional and would be equal per capita across provinces at a level that equalled the average amount spent on these programs by the two richest provinces in 1977, escalated annually by the three-year average of GDP growth. Half of the overall financing came in the form of cash transfers, and the other half was in the form of 13.5 personal income tax points and one corporate income tax point. Since the provinces were already in receipt of 4.357 PIT points and one CIT point, this represented a transfer of an additional 9.143 tax points (where a tax point is 1 percent of the federal PIT). This was the last transfer of PIT points from Ottawa to the provinces, so that subsequent increases or decreases in provincial PIT rates would reflect provincial decisions.

The challenge facing the 1982 round of the fiscal arrangements agreements was how to rework equalization in the context of (still) sky-high energy prices. In particular, the new program had not only to be affordable but it also had to exclude Ontario as a recipient. Initially, the notion of an Ontario standard held sway: all provinces would have access to the Ontario level of per capita revenues. Since Ontario had no fossil energy oil and since, by definition, it could not be eligible for equalization, the two criteria were satisfied.

In the event, the negotiations coalesced around the five-province standard (FPS), where the five provinces were Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and BC. It was essential that Alberta be excluded from the standard in order to minimize the impact of oil on equalization, and this was offset by also excluding the four Atlantic provinces, at that time the poorest. This was a stroke of political genius in that the FPS held sway until 2004, when Prime Minister Paul Martin wreaked havoc with the traditional approach to equalization via a series of arbitrary changes from which the program has yet to recover.

Finally, and as befits the 25th anniversary of the inaugural 1957 formula, the equalization principle was enshrined as s.36(2) of the Constitution Act 1982: “Parliament and the government of Canada are committed to the principle of making equalization payments to ensure that provincial governments have sufficient revenues to provide reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation.”

The remainder of the 1980s was punctuated primarily by some key economic developments — among others, the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement, the adoption of price stability as a Bank of Canada policy goal, and the introduction of the GST. The major transfer development was the set of bilateral off-shore energy accords with Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, which allowed these provinces to tax their offshore energy resources as if the provinces were the sole owners. Given that a separate tax base was created for Newfoundland and Nova Scotia within the equalization formula, the operation of the FPS program would have reduced other equalization flows to these provinces, dollar for dollar, in terms of the off-shore revenues. Ottawa’s solution to this was to enact the peculiarly termed, but particularly relevant, 1994 “generic solution,” i.e., a province with at least 70 percent of a tax base can shelter 30 percent of its revenues arising from entering the equalization formula. While Saskatchewan also had at least 70 percent of several of the various FPS energy tax bases, it did not have 70 percent of the overall or national-average tax base (which included Alberta) for these categories, so that it was not allowed to take advantage of the generic solution. This was one of the key factors that resulted in the FPS equalization program effectively confiscating the province’s energy royalties. Specifically, in fiscal year 2000/01 Saskatchewan’s energy revenues totalled $1.04 billion and its equalization clawbacks on these revenues totalled $1.13 billion! Intriguingly, all other have-not provinces were better off fiscally (in terms of equalization) because of Saskatchewan’s energy revenues. Arguably, this served as one of the triggers for the abandonment of the FPS standard in 2004.

Returning to the federal provincial cash transfer front, the 1990s were truly transformative. After a series of cuts and freezes to federal transfers (e.g., the cap on the CAP (Canada Assistance Program), which limited to 5 percent the annual transfer increases over the 1990/91 to 1994/95 period and whose cost to Ontario ran into double-digit billions; and after a set of a freezes and caps on health and PSE transfers over a similar period) Finance Minister Paul Martin really lowered the boom on the provinces in his historic 1995 budget. Specifically, Martin rolled established programs financing (EPF) and CAP transfers into the newly created Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST), which he then cut by nearly $6 billion (from $18.3 billion to $12.5 billion by 1997-98), and obviously much more, cumulatively. Intriguingly, this downloading of a large part of the federal deficit to the provinces via the transfer system triggered what turned out to be a most creative bout of nation building by the provinces. Under the aegis of the reinvigorated Annual Premiers’ Conferences (APCs), the Ministerial Council on Social Policy Reform and Renewal produced “A Report to Premiers” in December 1995, a document that still ranks as Canada’s most impressive statement of social policy principles and goals. One immediate and significant result was the introduction of the Canada Child Tax Benefit in Martin’s 1997 budget, a recommendation contained in “A Report to Premiers.” Similarly, the popularity of the premiers’ focus on social policy eventually led Ottawa to get on the social policy bandwagon, the result of which was the Social Union Framework Agreement (SUFA). And, led by the newly elected Premier of Quebec, Jean Charest, the APC evolved into the Council of the Federation (COF) in December of 2003. Thus far the COF has played a key role in improving the internal economic union, and one expects that it will continue to play an important role in internalizing the various provincial social, economic and environmental externalities. My view of this post-1995-budget evolution toward the COF is that the provinces realized that in order to preserve, let alone increase, the degree of decentralization in the federation, they would have to embrace a corresponding degree of coordination/ responsibility for their collective policy actions. The COF is a significant step in this direction.

However, the COF is also a lobby group for the provinces, and its initial cause célèbre was to press for restoring fiscal balance in the federation. And in its first meeting in July 2004, the COF responded to Prime Minister Paul Martin’s commitment in the 2004 election to convene a First Ministers’ Conference (FMC) on health care wait times in the fall of 2004 with two recommendations: one, that the Canada Health Transfer be increased to 25 percent of health spending (i.e., filling the so-called “Romanow gap”) and then be indexed, and, two, that equalization be increased immediately to its historic high (2001) and that the formula be shifted from the FPS back to a National Average Standard (NAS). By way of an intriguing aside, the COF also recommended that Ottawa take over Pharmacare, a proposition that Ottawa did not react to but one that may not be permanently off the table.

In the event, Ottawa’s health accord gave the provinces $41 billion over 10 years (the Romanow gap plus 6 percent indexing). On the equalization front, Martin introduced the “New Framework,” which followed the COF recommendation by increasing the level of equalization to its earlier historic high ($10.9 billion). But then Prime Minister Martin went beyond this to fundamentally alter the equalization formula. Henceforth, this $10.9 billion of equalization would grow by 3.5 percent, irrespective of the degree of interprovincial fiscal disparities. Hence, the role of the formula would be to only determine the allocation of this fixed pool across provinces and not the size of the pool. Overall, the 10-year agreement would add $33 billion to equalization.

Complicating all of this was the stand-off between Prime Minister Martin and Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Danny Williams (and to a lesser degree Nova Scotia Premier John Hamm) deriving from a private telephone conversation between Martin and Williams in the final weeks of the 2004 federal election, in which Martin is purported to have promised Williams that the revenues from the offshore would be protected from equalization clawbacks. In the event, by lowering the flag, Premier Williams succeeded in raising the (equalization) standard: the new 2005 Offshore Accords provide full compensation until 2012 to Newfoundland and Labrador, and to Nova Scotia, for any reductions in equalization payments as a result of increased revenues from offshore developments.

Recognizing that the equalization file was becoming increasingly arbitrary and problematic, in March 2005 federal Finance Minister Ralph Goodale established the Expert Panel on Equalization and Territorial Formula Finance, whose report is henceforth referred to the O’Brien Report, after its chair Al O’Brien, former deputy minister of finance for Alberta. The recommendations of the O’Brien Report were fully incorporated into the Conservatives’ 2007 budget. Among its provisions were: the formula would revert to determining both the amount of equalization and its distribution across provinces; the new formula would maintain the national average standard, but include only 50 percent of resource revenues (i.e., NAS-50); the 30+ revenues sources would be equalized through five tax bases — the PIT, the CIT, property tax, sales tax and natural resources; the tax base for resource revenues would be the actual amounts of resource revenues collected; a cap will be imposed so that, as a result of equalization, no receiving province ends up with an all-in fiscal capacity (i.e., NAS with 100 percent inclusion of resource revenues) larger than that of the nonreceiving province with the lowest fiscal capacity (assumed at the time to always be Ontario); and finally, the data entering the formula would be in the form of a three-year moving average, lagged two years.

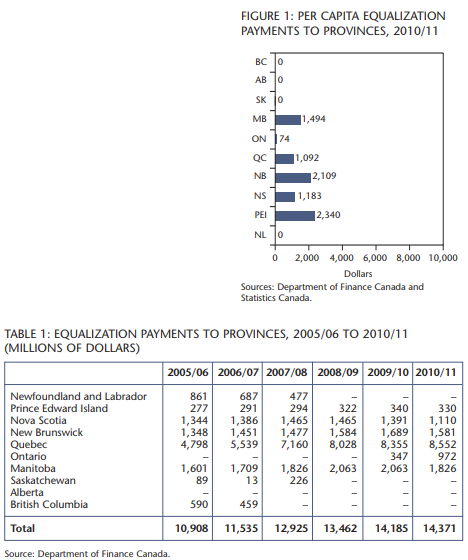

However, thanks to the upward spiral in the price of oil (which approached $150 per barrel in mid2008), this comprehensive rethinking and reworking of equalization was overwhelmed by events and had to undergo yet another transformation in the 2009 federal budget. By now, readers might guess that again the trigger was that Ontario had joined the ranks of the equalization-receiving provinces. Data for equalization payments from 2005/06 to 2010/11 appear in table 1, and the per capita values for the current year are shown in figure 1.

In elaborating on the several interrelated facets relating to this latest revision, it is a pleasure to acknowledge the excellent paper by Michael Smart, “The Evolution of Federal Transfers since the O’Brien Report.” First, under pressure from surging resource revenues, the total amount of equalization have again be fixed (and indexed). Second, and a contributing factor to the first, BC has now become the nonreceiving province with the lowest fiscal capacity, with the result that the equalization cap will be $800 per capita higher (than with Ontario as the cap), so that the equalization payments to the resource-rich receiving provinces will likely rise. To eliminate this possibility, the cap has been redefined to equal the per capita average over the receiving provinces of the sum of national average fiscal capacity (including 100 percent of resource revenues) and equalization.

But with Ontario as a have-not province, the equalization program is likely to become unaffordable. In the 1977-82 era, Ontario being a recipient province meant that an extra dollar of oil revenues would lead to a 75 cent increase in equalization. In the current time frame, because the resources base includes more than oil, and because Newfoundland and Saskatchewan are now have provinces for resources, the increase in equalization is in the range of 57 cents. This would still break the equalization bank, especially given the likelihood of rising energy prices. Obviously, this was the real reason why the equalization program was returned to a fixed-pool framework.

A further problem, however, is that an increase in Ontario’s equalization (either from escalating energy revenues or because Ontario’s fiscal capacity is falling, in absolute terms) means that under a fixed pool there are fewer equalization dollars for the traditional equalization receiving provinces. And because Ontario is so large and energy prices are so volatile, the result will likely be considerable variability in the payments flowing to the traditional recipients. Indeed, one can anticipate that these provinces will argue for a return of the “personal income override,” which would once again exclude Ontario from equalization. In other words, equalization has resumed its unenviable state as an accident waiting to happen.

Some elaboration of the details in table 1 may help clarify aspects of the above analysis. Most striking is the huge increase in Quebec’s equalization, from $4.798 to $8.552 billion. Indeed, this increase was larger than the overall increase in equalization over this period. The reason for this is that with an escalating fixed pool, and with Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and BC becoming have provinces, Quebec garners a much larger share of the equalization pool. At the margin, and with Ontario excluded, Quebec gets 69 cents of every additional equalization dollar arising from energy revenues. However, with Ontario now in the have-not group, Quebec’s 68 cent share of the marginal equalization dollar falls to 32 cents, with decreases as well for the other receiving provinces. Small wonder that they would like to keep Ontario out of the recipient pool.

While one presumes that the system will find ways of hobbling along, prodded by self-interested provinces and aided by very able plumbers, it may be useful to conclude this overview of federal-provincial financial relations by briefly highlighting a series of alternative perspectives or practices elsewhere that might be brought to bear on rethinking aspects of the theory and/or mechanics of equalization, and the transfer system more generally. Many, perhaps all, of these alternative perspectives may be viewed as unacceptable. Nonetheless, each sheds light on selected features of the current arrangements, features that often go unnoticed.

The first relates to the manner in which hydro rents are treated within the existing formula. Currently revenues from this sector are in the form of either (1) charges for use of the hydro potential, which enter the formula as resource revenues or (2) as remittances from provincial Crown corporation, which are classified as business revenues. As the O’Brien Report noted, provinces can influence the form in which these revenues enter the formula so the negative impact on their equalization entitlements is minimized. This has become more important recently, because of the prospects for exporting hydro to the US, likely at prices that exceed those in the exporting province. An option suggested by the O’Brien Report was to work toward a framework to calculate hydro rents, whether they are left in hands of hydro consumers via low prices or accrue to provincial governments. Beyond this, energy prices and therefore hydro rents will probably rise as progress is made in moving toward a green economy and society. To be sure, the O’Brien Report ended up not recommending this course of action, because it would be too difficult and controversial. However, not following along this path, if hydro rents do rise, may well make continuing with current approach to resource equalization too difficult and controversial.

A second perspective might focus on the funding inequity (the provincial source of the increase in equalization differs from the provincial source of Ottawa’s revenues to fund it), and take the view that Ottawa should not equalize tax bases (1) that are large and variable across provinces, and (2) from which Ottawa receives no direct revenues.

This would amount to excluding energy revenues from the formula, an option that the nonresource provinces would clearly reject. But Ottawa could invite the provinces to embark on a self-financing interprovincial revenue-sharing pool for resource revenues that could be run through the COF. For example, all provinces could put 20 percent of their resource revenues into the pool and then draw out their population share. While the energy provinces are almost certain to reject this revenue sharing option, it might be noted that a version of a revenue-sharing pool exists in the German federation.

The third and fourth perspectives are related in that they address many Canadians’ concern that we are overequalizing. I want to come at this from the vantage point of what is usually referred to as “capitalization.” The third perspective focuses on the revenue, where the property tax base is a good example. It has recently been redefined to take account of the high land values in BC and other places, so that BC’s share of the formula-defined property tax base is larger than its share of actual property tax collections. Similarly, the PIT base for Ontario has been adjusted upwards because it has a higher share of high income earners, so that Ontario’s share of the equalization formula’s PIT base is larger than its actual share of PIT tax collections. Given that the revenues to be equalized for property taxes and for the PIT are huge ($55 and $79 billion, respectively), a couple of percentage point increases in favour of the receiving provinces’ deficiencies makes a very significant difference.

In fiscal year 2000/01 Saskatchewan’s energy revenues totalled $1.04 billion and its equalization clawbacks on these revenues totalled $1.13 billion! Intriguingly, all other have-not provinces were better off fiscally (in terms of equalization) because of Saskatchewan’s energy revenues. Arguably, this served as one of the triggers for the abandonment of the FPS standard in 2004.

Enter the companion (fourth) perspective. If one is going to invoke capitalization, there is a much stronger case to be made for doing this on the spending side, rather than on the revenue side. Note that s.36(2) of the Constitution Act, 1982, states that revenues be reasonably comparable across provinces so that reasonably comparable public goods can be delivered. However, because well over half of public goods and services are somehow related to the level of wages, rents, etc., it takes more revenues in higher-wage and higher-rent provinces to deliver a comparable bundle of public services (e.g., one police officer, one social worker, one welfare recipient, one appendectomy, one nurse, and so on). Hence, Ontario needs more revenues per capita than New Brunswick does to deliver comparable services. But we make no correction for this. Therefore, because of the impact of capitalization on the revenue side, our equalization program brings New Brunswick’s overall per capita revenues to a higher level than those of Ontario. The combined effect is one of the reasons why the earlier-noted Frontier Centre for Public Policy study shows that the equalization-receiving provinces provide more “bundles” of public services than do the rich provinces. To be sure, if New Brunswick needed more bundles per capita (i.e., had greater needs than Ontario), then this outcome would be appropriate. But this is far from obvious, and in any event, Canada’s equalization program has always assumed that per capita needs are everywhere identical.

Along similar lines, one might note that the oft-cited rationale for the lack of an equalization program in the US federation is that any fiscal differences are capitalized (i.e., it takes more revenues to deliver a bundle of services in New York than it does in Mississippi), so that in the final analysis there is nothing to equalize, as it were. In the Canadian context, this US assumption of 100 percent capitalization would be wholly unacceptable, but the tandem of the third and fourth perspectives brings to light the likelihood that the formula is overequalizing. At the very least, it is passing strange that the US uses capitalization to argue that there is no need for equalization, whereas we employ it to increase equalization!

My final two observations bring the federal-provincial cash transfers back into the analysis. The first observation is that the current system of cash transfers is very generous — health care transfers are rising at 6 percent in a 2-percent-inflation environment. One expects that after 2014 these will be scaled back closer to the rate of inflation. If the real costs of health care increase, the provinces will probably have to resort to tax financing. Now that almost all provinces have converted their sales taxes to the GST/HST format, one option would be to follow Nova Scotia and Quebec in taking up the 2 percent GST tax room vacated by the Conservatives early in their mandate. Another would be to impose a deferred user fee for certain medical services, which would be reconciled via the provincial PITs and could be made quite progressive because they would be linked to one’s income. Quebec has recently moved in this direction. Intriguingly, since both of these are tax measures, if they become widespread, they would likely be eligible for equalization, in which case the combined result would be an increase in provincial taxes and a reduction in the growth of cash transfers partially compensated for the poorer provinces via an increase in equalization. The key message here is that the transfer system is sure to play a role (proactive or reactive) in any shift in how health care is funded.

My last observation is that, after equalization, Alberta has a per capita fiscal capacity that is in the range of $5,000 above those of the traditional equalization-receiving provinces, along with $2,000 for Saskatchewan and just over $1,000 for Newfoundland and Labrador. While s.36(2) of the Constitution Act 1982 may not be justiciable, these data would nonetheless appear to fall way short of the spirit intended by the equalization principle and may eventually lead to citizens in some provinces not having access to reasonably comparable public services. Assuming that interprovincial fiscal disparities, after equalization, become an issue, then one approach would be to “revenue-test” the federal-provincial transfers (CHT, CST etc.). Currently, these transfers are running about $1,000 per capita. One variant of revenue testing could work as follows. Calculate the per capita national average of the sum of own-source and equalization. If a province has, say, over 110 percent of this all-province average, then its federal cash transfer would decrease by 20 cents for every dollar of its revenues in excess of the 110 percent threshold. The resulting federal savings would be used to perform further rounds, until the cash transfers are fully distributed. Hence, if a province has $5,000 per capita above the threshold, then its $1,000 per capita federal cash transfer would fall to zero. However, the province would still have the $5,000. While this may seem radical, revenue-testing, or its close relative, income-testing, is employed in many policy areas (the Canada Child Tax Benefit, Employment Insurance, the Guaranteed Income Supplement, Old Age Security, and so on) and some version of it characterizes most federal systems.

Having thus managed to impugn every province, implicitly or explicitly, I will close on a hopefully more comforting note. Australia is the most centralized and egalitarian federation, and it has the most comprehensive and egalitarian set of fiscal arrangements — on the equalization front, the states revenues are equalized both up and down to the national average. Germany is the next most centralized federation, with “uniformity of living conditions” enshrined in its Basic Law and a revenue-sharing pool among Länder. At the other end of the spectrum is the rugged individualism of the US federation, where the absence of concern about point-in-time income distribution has its counterpart in the absence of a formal equalization program. And Canada’s intergovernmental tax and transfer system reflects the decentralized nature of our federation and the “Peace, Order and Good Government” of our constitutional rhetoric. The fascinating story in all this is that despite all the assumptions, short cuts, bargaining and special interests that are inevitably brought to bear on the design of the intergovernmental fiscal arrangements in all federations, in the final analysis the financial arrangements are anything but arbitrary. Indeed, they complement the existing tax and expenditure assignments in ways that integrate fiscal federalism in directions consistent with the implicit or explicit values and norms that underpin their respective federations.

From this perspective, the myriad of intergovernmental problems highlighted above are part of the ongoing challenge of restructuring our fiscal arrangements, not only in light of the dictates of the new global order, but also in ways that will ring true with the values we hold with respect to our federation and our fellow citizens.

Photo: Shutterstock