Climate change is a classic example of a “wicked” problem. The scientific evidence is increasingly clear that we must achieve a massive global reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in the next few decades, or risk potentially devastating ecological and economic consequences.

To achieve these reductions, there is no technological quick fix as was seen with other pollution problems, such as acid rain or ozone depletion. Greenhouse gases are pervasive across the economy, emanating from a vast array of business and household activities. The main cause is our dependence on fossil fuels for energy — for our homes, industries and cars. The only solution is to transform our energy systems. We must exponentially increase the efficiency of our energy use. As importantly, we must decarbonize our energy production systems — shifting to “clean” primary energy sources (wind, solar, small hydro, etc.), and capturing carbon emissions from fossil-fuel-based sources.

This will not be easy, or quick. Our current energy infrastructure is deeply embedded — physically, socially and economically. It is largely interconnected, and much of it is long-lived. Systems of energy production (power plants, refineries), use (roads, buildings, plants) and distribution (grids, pipelines) will take years — and sometimes decades — to replace. For Canada, one of the world’s largest per capita users and producers of energy, these transformations imply significant economic and social change. At the same time, they present new opportunities to lay a strong foundation for competitiveness in the emerging low-carbon economy.

Despite two decades of lip service, Canada has made very little progress on this critical challenge of transforming our energy systems — or tackling climate change generally. This inaction is partly because these changes raise very difficult political issues that cut across regional, sectoral, generational and socio-economic lines. But other developed countries have made much more progress than Canada. And the US, our major competitor and trading partner, now seems poised for its own leap forward. We are falling behind in the transition to a low-carbon economy. Policy leadership is desperately needed.

Transitioning to cleaner energy systems will require many changes. But the most important one is to put a meaningful price on carbon. A carbon price will rapidly ripple through the economy, reaching all energy users and producers, and motivating new investments and behavioural changes — much more quickly, pervasively and efficiently than could be accomplished by regulating all of these activities. And if well designed, a carbon price also can finance tax cuts and public investments in clean technology and infrastructure to build a stronger economy for today and tomorrow.

There are two main ways to price carbon: a tax or fee on emissions; or a cap-and-trade system — in which firms that go below their emission limit may sell the excess “credit” to firms that exceed their limit. Each approach puts a price on emissions, and each has two principal advantages over a traditional “command and control” approach to carbon regulation: it can achieve reductions at much lower cost (which allows for greater reductions), and it creates a continuous incentive for clean innovation, since there is an economic reward for each unit of emission reduction.

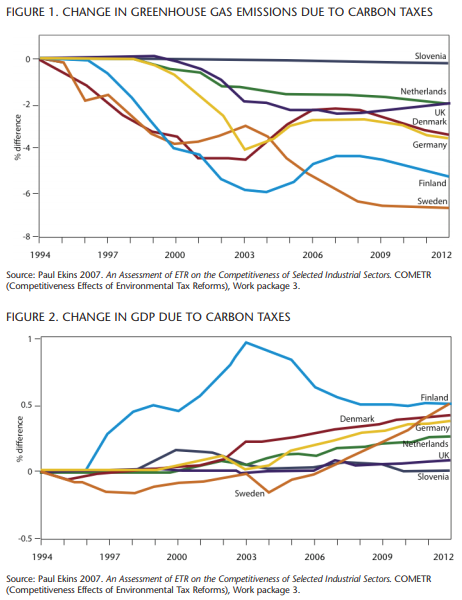

These benefits have been demonstrated in other places. For example, the US acid rain program, which used a cap-and-trade system to reduce SO2 and NOx, achieved 25 percent greater emission reductions at cost savings of 20 to 50 percent compared to command and control. And in Norway, a hefty carbon tax has motivated the major oil producer to become a leader in carbon capture and sequestration. Indeed, a recent study conducted for the European Commission assessed carbon taxes in seven European countries, and found they were effective both environmentally (emission reductions of 2 to 6 percent) and economically (small, positive effects on GDP, mainly due to tax shifting).

No matter the instrument, a carbon pricing policy should be:

- Comprehensive, with no exemptions: A price signal should apply across the economy, providing an incentive to all businesses and households to cut emissions. In a cap-and-trade system, emission permits should be fully auctioned or priced (some transitional accommodation may be needed, such as for energy-intensive, trade-exposed sectors).

- Nationwide: The federal government should take the lead in pricing carbon, or establish a common framework for a minimum carbon price. A balance is needed between allowing regional innovation (such as British Columbia’s tax) while avoiding costly policy fragmentation.

- Simple and readily implemented: Policies should avoid complex rules and exceptions. Ones with shorter lead times to take effect are preferable, since fast implementation will make long-term deep emission reductions less expensive.

- Transparent and accountable: There should be transparency with respect to policy objectives (e.g., price and/or quantity targets) and implementation, and use of revenues.

- Complemented where a price signal alone is insufficient: Non-price policies (e.g., regulations or incentives) should also be used in certain situations, such as for activities that are price inelastic, or to stimulate accelerated technology research and development. The carbon price itself should be:

- Environmentally effective: The price should be set at a level that will achieve the jurisdiction’s interim and long-term emission reduction targets.

- Comparable to that in other countries: To minimize competitiveness impacts and avoid trade sanctions, Canada’s carbon price should be in line with other countries’. This does not nullify the need for initial leadership in adopting carbon pricing.

- Predictable but adaptable: A strong carbon price should be initiated swiftly. It should rise steadily to enable adjustment and planning. It should be recalibrated if required by changing science, international goals or emission reduction response. An independent advisory panel would promote transparency and objectivity.

Weighing these factors, most economists come out preferring a carbon tax. They point to several main advantages, including its simplicity (it builds on the existing tax system), comprehensive coverage, ease of establishment (BC’s carbon tax was developed in just a few months), low transaction costs (no trading) and greater price certainty — provided the price is high enough to achieve emission goals. However, a well-designed cap-and-trade system can be almost as effective, and comprehensive, and brings the added benefit of certainty of emission reductions.

The political momentum in North America now seems headed in the direction of cap-and-trade, with the US and Canadian federal governments committed to this approach. However, the politics of this issue are evolving rapidly. With countries like China, Sweden and France (and many US Republicans) actively promoting a tax, it is too early to predict, as of this writing, what direction will come out of the Copenhagen climate meeting in December, or how that might affect domestic policy.

If Canada does pursue a cap-and-trade system, it will be important that it incorporate the design elements from the above eight principles. In particular, the system should cover as much of the economy as possible (not just industrial emitters), set a target stringent enough to meet our climate goals and contain features to reduce price volatility — which creates uncertainty that can diminish investment in clean technologies. Each of these elements is found in the bill passed by the US House (Waxman-Markey), and in the April 2009 recommendations of Canada’s National Roundtable on the Environment and Economy.

The mechanism to manage price volatility will need careful attention. The current federal plan for a “safety valve” price of $15/tonne (through contributions to a technology fund) could dampen the price signal needed to drive change, and might open the door to trade sanctions under the US bill. These problems can be avoided by financing clean technology support through revenue from carbon permit auctions, rather than a safety valve price. Moreover, price volatility and competitiveness concerns can be better addressed through other means, such as revenue recycling. In addition, to maintain a robust carbon price it is wise to limit the use of offsets (and ensure they represent real reductions).

There are two main ways to price carbon: a tax or fee on emissions; or a cap-and-trade system — in which firms that go below their emission limit may sell the excess “credit” to firms that exceed their limit.

The other key question is about charging for emission rights. With a tax, the users pay for every tonne of carbon they emit. With cap-and-trade, they pay for all emissions over their assigned cap, but it is an open question whether they pay for the right to emit up to that cap. Most economists argue that a cap-and-trade system should charge for every tonne of carbon emitted, by auctioning allowances or charging a price for them (one “allowance” is issued for each tonne of permitted emissions). Allowances have real value — the opportunity cost of emissions.

Free allocation is a decision to pay that value to existing emitters, with the highest subsidy going to the highest emitters, and to impose the cost of that subsidy on society — a far from ideal approach. Auctions are also a more simple and transparent approach to distributing allowances than government allocation — which is rife with potential for rent seeking (i.e., “gaming the system”). Finally, auctions can make funds available to buffer the impacts of climate policy on vulnerable groups and sectors, or for other important economic or environmental goals.

Despite these advantages, in every cap-and-trade system there is strong pressure on governments to allocate most or all allowances for free — as emitters seek to reduce their compliance costs. This was clearly seen in the US Waxman-Markey bill, where the initial goal of 100 percent auctioning (endorsed by President Obama) was whittled down to 15 percent by the time it passed the House. This was largely a function of US congressional politics and the concessions needed to assemble a majority of votes. Canada would be well advised to resist these political pressures, and go the route of auctioning or charging for allowances — recognizing that some transitional accommodation may be needed for vulnerable sectors or groups. Doing so creates an opportunity to show climate leadership, and to build a system that is fairer, and likely better for the economy overall, than the US approach.

A critical part of making a carbon pricing system economically effective, and fair, is what is done with the revenues generated. An economy-wide carbon tax or an auction-based cap-and-trade system could generate revenues in the range of $10 billion per year (assuming a price of $15/tonne) — and more in later years as prices rise. That is a substantial amount of money. There are a number of options for how to reinvest it, including:

- reducing distortions in the broader corporate and personal tax system — by cutting taxes on income, investment or labour;

- addressing competitiveness issues arising from the carbon price — e.g., with time-limited tax breaks or refunds to trade-exposed, energy-intensive sectors;

- offsetting the proportionally greater impact of a carbon price on vulnerable regions or low-income households — with targeted tax refunds (as was done in BC);

- funding climate adaptation programs (domestic and international); and

- funding low-carbon public infrastructure, and supporting clean technology development and research.

Each of these options has some merit — for reason of equity, economy or ecology. Certainly government should use a portion of the revenues to address the adverse effects of a carbon price on vulnerable groups, regions or sectors.

In healthy economic times, many governments also would choose to recycle a large portion of revenues into cutting taxes on labour or income, to spur investment, employment and growth (as was done in BC, and many EU countries). However, we are now in a time of massive deficits, and it will be hard to justify further tax cuts — on top of already committed cuts to corporate taxes. Indeed, carbon revenues may help to avoid the need for tax increases.

In our present economic circumstances, a strong argument can be made for investing a large portion of the revenues to support low-carbon infrastructure and clean technology development. This can be justified on three main grounds.

First, there is a need for a major investment in public infrastructure to support a low-carbon economy. The list of key investments includes a smart electrical grid (to support more efficient energy use and enable clean power producers to feed in); public transit (more buses, rails and trains to replace cars and planes); clean energy generating facilities (both public and private); distribution capacity to support carbon capture and storage; energy-efficient public building and housing; and research to advance low-carbon technology, innovation and systems.

Second, transforming our energy systems will also require a major private investment in infrastructure and technology — in electric cars, carbon capture, biofuels, clean power, energy-efficient buildings and plants, and much more. In theory a strong carbon price, by itself, would create the incentive for the necessary investments — and make them profitable. However, the prices being proposed for coming years — in the range of $15 to $30/tonne — are far too low to drive the scale of investment and change needed. This investment cannot wait until prices rise to a higher level (possibly in a decade); given the urgent need to start turning over our energy infrastructure and reducing emissions, it must begin right away. Therefore, it seems likely that public incentives will be needed to supplement a carbon price, at least for the coming 5 to 10 years, in order to kickstart private investments in clean energy infrastructure and technology.

Third, countries around the world are competing to be the home for new clean technologies that will blossom in a low-carbon economy. Significant public incentives are being provided to support the development of these industries, and jobs. The US, for instance, is devoting 12 percent of its stimulus package, or $94 billion over 10 years, to energy efficiency, renewable power and other green investments — far more than Canada on a per capita basis. And many countries in Europe and Asia are spending even more. To compete, Canada needs to provide similar levels of support — focused on key areas of need and opportunity for our economy.

This massive public (and private) investment needs to be funded at precisely the same time as sizable government deficits will be putting exceptional strain on the public purse. But unlike the US and many European counties, Canada has no appetite for long-term deficits. The best solution lies in the revenue from carbon pricing. Those who emit carbon will help fund the investments to reduce it — “user pay” — and benefit themselves along the way.

If, as seems likely, Canada adopts a cap-and-trade system, a choice to auction or charge for most of the allowances would provide the missing ingredient for helping Canada become a world clean energy leader, even as the raw materials and technologies of the energy sector transform. Indeed this is exactly what Barack Obama proposed in his 2010 budget — a $150billion, 10-year clean energy investment funded by carbon revenues — although Congress has now horse traded away much of the intended revenue base. And there will no doubt be strong pressures for Canada to follow a similar course, and give away most allowances for free. If politicians succumb to this pressure and delay moving to broad-based auctioning, as the US is doing, we delay being able to make major investments in clean technology and infrastructure. However, if we resist this temptation, and put a price on all carbon emissions, we have an opportunity to do what President Obama wants to do — combine the “pull” of carbon pricing with the “push” of public investment to drive a clean energy transformation.

Of course the generation of carbon revenues raises the thorny question of who should receive those revenues — federal or provincial governments? This area is strewn with political land mines, as painfully demonstrated by the National Energy Program and its legacy. Provinces claim that carbon revenues, especially where generated from provincial industries or resources (oil and coal), should rest with them. Ottawa argues that carbon pollution is a federal issue — particularly given its global nature — and requires a nationally driven response. Both claims have some validity. The issue is further complicated by the fact that some provinces (BC, Alberta and Quebec) are already generating revenues from carbon pricing, and others may soon follow suit.

Navigating these federal-provincial fiscal waters will be no easy task, and likely will require some sort of revenue-sharing arrangement. But amidst the challenges, there also lies a real opportunity — to potentially lay the foundation for a national energy framework. Canada has long lacked a coordinated federal-provincial approach to energy development, use and sustainability. The Constitution gives Ottawa relatively few cards to play in this field, and provinces have generally resisted (often vigorously) federal attempts to wade into the area. The emergence of a significant carbon revenue base, and the reality of needing to share it, could change this dynamic.

The need to carve up carbon revenues — especially ones generated under a federal regulatory instrument — invites dialogue and agreement on common principles for how those revenues will be used. Indeed, one could argue that such cost-sharing was a critical element in establishing coordinated national approaches in the areas of health care and social programs, and to a lesser extent municipal infrastructure development. While intergovernmental collaboration in these fields is far from perfect, and not lacking in conflict, it is at leas grounded in common principles. And it is vastly superior to anything that exists in the energy field — or the environment field generally.

Provinces claim that carbon revenues, especially where generated from provincial industries or resources (oil and coal), should rest with them. Ottawa argues that carbon pollution is a federal issue — particularly given its global nature — and requires a nationally driven response. Both claims have some validity.

Which is not to say that developing a national energy framework, or any type of coordinated approach, will be easy. But at least the need for regulatory coordination, and more importantly revenue sharing, will bring the jurisdictions to the table in a way that has not happened to date. And they will be supported in doing so by a growing consensus among energy companies and environmental groups that such a coordinated approach is badly needed — to move forward on combating climate change, and to spearhead the pricing, programs and investments required to transform Canada’s energy systems and position us to prosper in the emerging low-carbon economy.

The consequences of failing to put a meaningful price on carbon are growing: a delayed transition to a low-carbon economy, stranded infrastructure investment, rising costs of reaching targets and a cluttered and increasingly fragmented Canadian policy landscape marked by half measures and a patchwork of provincial policies. Moreover, we must address the growing imperative to at least keep pace with the US — and ideally get ahead — on the new technologies and infrastructure of the low-carbon economy.

A different outlook and approach is needed. Governments, businesses and consumers must come to terms with the need for a clear carbon price signal across the economy, and the fact that there will be winners and losers as the economy adjusts — as happens with any major economic transformation (think free trade). The task is how to make this as manageable as possible, without sacrificing the integrity of the pricing program.

We are dealing with how to drive a fundamental transformation of the energy underpinnings of our economy. The key lies in linking an effective system for climate compliance with a strategic approach to recycling the revenues arising from permit auctioning and/or a tax. A strong price signal across the economy can drive a largely market-based response to reducing emissions. A portion of the revenues should be directed to tax relief, particularly for vulnerable groups, regions or sectors. And a significant share should be directed to support for clean technology and infrastructure investment — particularly given the current fiscal constraints and the (regrettable) likelihood of a too-low carbon price. This two-pronged approach will help to simultaneously build the foundation for future competitiveness and climate compliance, and craft a broad coalition to buttress bold government action.

Fashioning such a far-sighted policy, and the accompanying energy transformation, will require a coherent, if not coordinated, national effort — perhaps built around agreement on the sharing and use of carbon revenues.

An earlier version of this paper was prepared for the Energy Framework Initiative.

Photo: Shutterstock