In 1980, I was at the Skyline Hotel in Ottawa (now the Delta) and witnessed Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau come to a National Indian Brotherhood meeting of Chiefs. He asked the Chiefs to “treat Canada better than Canada has treated you,” as he revealed his intention to patriate Canada’s constitution from Britain — a bombshell that raised the question of whether Aboriginal and treaty rights would be part of the document.

From that salvo of Trudeau Senior to the initiatives of current prime minister Justin Trudeau, there has been an unyielding policy war of attrition toward Indigenous people (First Nations, Inuit and Métis). The current Liberal government might be raising the notion of getting rid of the Indian Act and restoring a nation-to-nation relationship, but history tells us the real objective is to hollow out and ultimately nullify any rights that Indigenous peoples have to meaningful self-determination.

The constitutional reform process

After Trudeau’s announcement in 1980, Chiefs and Indigenous community members began to mobilize. The Justice Minister, Jean Chrétien, had initially agreed to demands by the Alberta and Saskatchewan premiers that Aboriginal and treaty rights be left out of the draft constitution. In response, the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs organized a train to travel across Canada with Ottawa as its destination — it was dubbed the “Constitution Express” by the organization — to demand that recognition of Aboriginal and treaty rights be put back into the draft.

In the United Kingdom, a group of leaders from historic treaty nations lobbied MPs and Lords against the so-called “Canada Bill” and even launched an unsuccessful court case in the UK to stop the patriation process. To counter the government’s narrative about Canada having two founding nations, the term “First Nations” was coined, and the Chiefs reconstituted the National Indian Brotherhood as the Assembly of First Nations in 1982.

As a result of pressure brought to bear by Indigenous peoples and Canadians who supported them, section 35 recognizing Aboriginal and treaty rights was entrenched in the Constitution Act, 1982: “The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.” A second section, 37, provided that a First Ministers’ Conference be held within a year, and include on its agenda constitutional “matters that directly affect the aboriginal peoples of Canada.”

The First Ministers’ Conference of March 1983, which covered “identification and definition of the rights…to be included in the Constitution of Canada,” as outlined in section 37, led to the Constitution Amendment Proclamation, 1983, which provided for at least two more First Ministers’ Conferences touching on Aboriginal matters. The proclamation also amended section 35 to include land claims agreements as treaties within section 35.1, and to guarantee gender equality between Aboriginal men and women.

There were to be three more First Ministers’ Conferences on Aboriginal matters (1984, 1985, 1987). The last one ended with a failure to reach an agreement on the meaning of section 35 rights between the representatives of the four national Aboriginal organizations, the Prime Minister, the premiers and the territorial government leaders.

Although there were many other issues on the agendas of those conferences of the 1980s, including Aboriginal title and historic treaties, the main issue was self-government. Was it an inherent right or a contingent, delegated right, granted by the Crown governments?

The Aboriginal leaders argued that the right of self-government was an inherent right already included in section 35, which needed only to be recognized properly by Crown governments. But the dominant metaphor that emerged about section 35, one articulated by the first ministers, was that section 35 was an “empty box,” to be filled up with agreements negotiated with the federal, provincial and territorial governments. This view held that self-government was a delegated right dependent upon reaching an agreement with Crown governments.

Meech Lake, Charlottetown and beyond

The 1987 First Ministers’ Conference on Aboriginal matters ended without agreement. Prime Minister Brian Mulroney moved on to the question of Quebec’s “distinct society” status, and the Meech Lake Accord, proposing several constitutional amendments, was born. It died three years later in 1990, thanks to Manitoba MLA an Cree Chief Elijah Harper’s running out the clock on the deadline for Manitoba to ratify the accord. (All ten provinces were required to ratify.) Harper opposed Meech Lake because First Nations issues from the section 37 process had not been resolved.

The Charlottetown Accord of 1992 included the explicit recognition of the “inherent right of self-government” in the proposed constitutional amendment package. A national referendum was held and the majority of the Canadian public voted against the accord.

In 1993, the Liberals won a massive majority government, leaving the Progressive Conservative Party with two seats. The Liberals during the election had committed to renewing the relationship with Aboriginal peoples by promising that “a Liberal government will act on the premise that the inherent right of self-government is an existing Aboriginal and treaty right.”

But subsequent negotiations with national Aboriginal organizations, and a leaked memorandum to cabinet in 1995 on the subject of rights, made it clear that the “empty box” idea of section 35 persisted. Any inherent right would need to operate within the framework of the Constitution in harmony with other jurisdictions, and did not entail sovereignty as understood in international law. The war of attrition continued.

The current Trudeau government

Since the federal election of 2015, the Trudeau government has embarked on a top-down, nontransparent approach to federal Indigenous policy. There are reportedly 40 to 50 “exploratory tables” with Indigenous groups. We don’t know the topics or with whom the federal government is holding discussions, but these discussions are supposed to feed into an equally opaque Working Group of Ministers on the Review of Laws and Policies Related to Indigenous Peoples.

The discussion results are to be presented to a “bilateral mechanism” — federal cabinet committees based on political agreements with three national Indigenous organizations representing the Inuit, Métis and the Assembly of First Nations, a Chiefs’ organization. This stealth approach to change policy and law bypasses the legitimate rights holders: the Indigenous peoples. They are the ones who have a right to self-determination, not the national Indigenous leadership groups.

Meanwhile, the federal Minister of Justice, Jody Wilson-Raybould, has issued 10 principles respecting the government’s relationship with Indigenous peoples to guide her federal policy and law review. But the 10 principles, and Canada’s Indigenous policy writ large, continue to be based on the Constitution Act, 1867. The Constitution enshrined the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments, leaving no room for recognition of equal Indigenous jurisdiction and power. The Crown’s assertion of sovereignty is at its core based on the “doctrine of discovery” — essentially, that the lands were vacant when Europeans arrived in the Americas and were there for the taking

Talks and negotiations based on these principles run counter to the right of Indigenous peoples to free, prior and informed consent over matters concerning their lands and resources, as outlined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Moving beyond the Indian Act?

The federal government recently announced it will split Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada into two departments: Indigenous Services, and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs. Trudeau said the move demonstrated “that we are serious about taking the right steps to move beyond the Indian Act.”

But the announcement signals only one thing to me: Our aspirations to decolonize as Indigenous peoples will be met with ongoing federal attempts to recolonize us, all part of the centuries-old Crown goals of “Indian” assimilation and the termination of collective Aboriginal and treaty rights.

Today’s recolonization will likely unfold on two tracks.

First, section 91(24) of the Constitution, which states that the Crown has jurisdiction over “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians,” will be used to impose national standards on the lives of Aboriginal peoples living on reserve through federal legislation, as has already been done with the First Nations Land Management Act, for example. With these laws, the Crown continues to set the parameters for how First Nations peoples are to live on their land, even once they opt out of the Indian Act.

Second, modern section 35 land claims and self-government agreements will be manipulated to modify, convert and extinguish the inherent sovereignty of First Nations. More self-government agreements will be signed with bands formed under the Indian Act. The political effect will be to convert these bands into a kind of ethnic Indigenous municipality rather than self-determining nations. Outlining a contingent set of rights through these agreements, rather than acknowledging the inherent right to self-determination, will in effect empty section 35 of any real political or economic meaning.

This is what I see Canada becoming without the Indian Act.

This outcome is not fair or just, and I predict the federal approach will lead to more conflict between Indigenous peoples and Canada. Remember that the modern high-profile conflicts between First Nations and Crown governments were led by grassroots Indigenous peoples, and not Indian Act band councils: Oka, Ipperwash, Gustafsen Lake, Burnt Church, Grassy Narrows, Caledonia and Elsipogtog.

The alternative approach to the Trudeau government’s law and policy review for development of new federal legislation would be for Indigenous peoples to select representatives to sit at a First Ministers’ Conference or constitutional conference to discuss implementation of UNDRIP, especially the articles on recognition of Indigenous self-determination and redistribution of stolen Indigenous lands, territories and resources; the agenda must include more than just dependency on federal fiscal transfer payments and federally designed programs and services. The selection of Indigenous representatives should be in accordance with article 18 of UNDRIP:

Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures, as well as to maintain and develop their own indigenous decision-making institutions. [emphasis added]

The outcome should be a constitutionally entrenched political agreement, not occasional edicts from a settler court, which is in a conflict of interest in claims against itself.

This article is part of the special feature The Indian Act: Breaking Its Stubborn Grip.

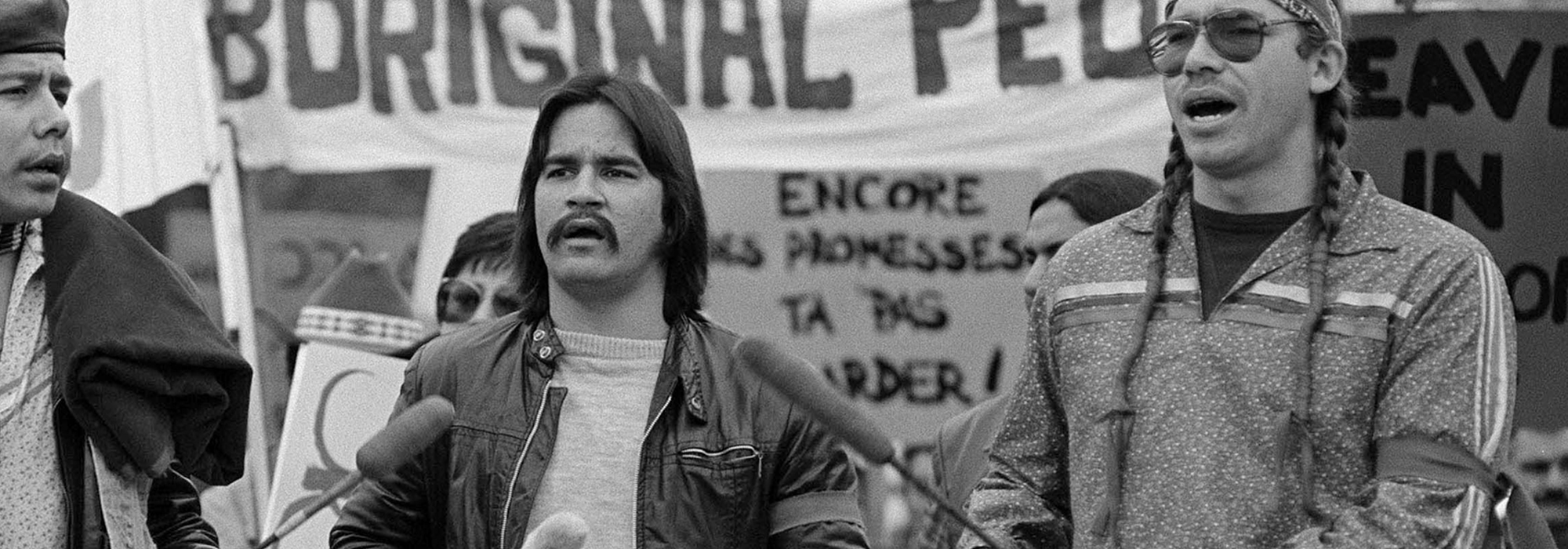

Photo: A protest on Parliament Hill on November 16, 1981, over the proposed elimination of Aboriginal rights in a new Constitution Act. Paul Nadjiwan of the Chippewas of Nawash is shown on the right. The Canadian Press/Carl Bigras.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.