In March of 1935, Adolf Hitler announced the rearmament of Germany in violation of the Treaty of Versailles. It had been just 17 years since the First World War had ended, a war that had resulted in roughly 700,000 British deaths and many more casualties.

And yet, when the UK held an election eight months later, in November of that year, the main issue was not the existential threat of a resurgent Germany, but domestic unemployment. This was, after all, still the Great Depression. Stanley Baldwin, the incumbent prime minister, was said to have been uncomfortable in foreign affairs. The campaign debate on defence and foreign policy, to the extent that it was engaged, was so muddled that for years since historians have argued about what, precisely, had been put before the public.

Of course, at the time no one could have foreseen the devastation the next 10 years would bring as clearly as we can see in retrospect. Still, there were plenty of warning signs, and it is hard not to think that the British politicians and the press of the day were focusing on the wrong things in the 1935 campaign.

Last year’s report from the UN’s scientific panel on climate change predicted a world of wildfires, food shortages and inundated coasts – a climate catastrophe – within 20 years if we continue on our current course of greenhouse gas emissions. And it will get much, much worse after that, the panel predicted, without quick and dramatic change.

In this election campaign, the Green Party leader, Elizabeth May, has explicitly drawn the parallel with the Second World War, and even if she muddled her facts a bit, it is hard to dispute that we could as a species be facing what William James called the “moral equivalent of war,” demanding personal as well as collective sacrifices. Viewed in that light, we could someday look back on the campaign of 2019 and wonder why the media weren’t talking more about climate change than they are. The reason they aren’t has a lot to do with the core dynamics of modern mass media and what is considered news by reporters and editors but also by the public.

When journalists decide what is news – a core professional function – they employ a set of loosely defined though widely shared “news values.” To take an arbitrary example, one news value is local relevance. A fatal car crash is news in the city where it takes place but not in a city just a few hundred kilometres away.

Two core news values are conflict and novelty. Where there is sharp disagreement, there is often news. When something is new or surprising (blackface!), there is news. When something is routine, for example undrinkable water on reserves, it is harder to convince a morning news meeting that you should spend your time doing that story that day.

It is not impossible to do stories that lack some of these news values. Indeed, the Globe and Mail published a deeply reported story on undrinkable water early in the campaign. But there’s a pretty good chance you don’t remember that piece as well as many others. In fact, it is worth a digression here on the role of news consumers in sustaining the prevailing news values.

There has been a lot of comment in columns and on Twitter in this election about the media obsession with polls and personalities. Usually the complaint is that what gets neglected is issues. And yet, the Globe produced a superb piece on suburban debt. Toronto Star columnist Chantal Hébert has written about the policy dilemma created by a Quebec court ruling on assisted dying, and her colleague Heather Scoffield has carefully analyzed the parties’ promises of affordability. At the CBC, the Frontburner podcast did a detailed walk through of the parties’ environmental platforms.

If these examples don’t quite fit your image of what the media have been doing these last few weeks, it is partly because editors have given them less prominence than the material you are more familiar with, and partly because you have been less likely to click on them or find them in your social media feed. In today’s rapid feedback newsrooms, there is often a large video display of the top 10 stories currently being read the most and for the longest. If coverage of issues were getting more traction with readers, believe me, there would be more of them, more prominently displayed.

But back to climate change. There are, of course, differences among the parties about climate policy and indeed as late as last spring some commentators thought this campaign might turn around climate change policy: the carbon tax and the pace of pipeline development. But so far, the party leaders have downplayed the issue. In an election campaign whose main theme so far has been “affordability,” no one but the Greens’ leader is likely to invoke the necessity of sacrifice on the scale the UN panel suggested is necessary.

The Conservatives have buried their objection to the carbon tax inside the broader theme of affordability partly because their feeble climate change policy is a sore point in Quebec, where they have ambitions. The Liberals, too, are vulnerable on climate change not only because some centrist voters don’t like paying the carbon tax, but perhaps more importantly because voters on the left dislike their support of pipelines. Even the Greens have decided to emphasize that they are not a one-issue party, a common stratagem for parties trying to fight their way in from the political margins.

Journalists find it difficult to establish a purchase on an issue when there is not a loud, open conflict between leaders. It is not their role to create issues, goes the news tradition, just to report on them. Early in my career at the CBC, a senior news manager told a meeting of academics that when all the premiers had agreed with then-prime minister Mulroney on the Meech Lake Accord with the support of the opposition leaders in Ottawa, he had felt it necessary to go outside this charmed circle to find critics and engender a discussion of one of the biggest proposed changes to the constitution in Canadian history. Under pressure from the Mulroney government, he was disciplined by the CBC.

Besides conflict, the other core news value missing from the climate change story is novelty. In this campaign, the parties have struggled to get the media excited even about the subjects they do want to talk about. The Conservatives pledging a tax cut? They have been doing that since Stephen Harper created the modern party in 2003. The Liberals promising more day care? That has been a feature of every Liberal election campaign since 1988 (when John Turner screwed up its roll out). Even the Greens’ policies, urgent as they argue they should be, are not fundamentally different from what they have been proposing in election after election. (Note that I had no trouble finding links for any of these stories; reporters are writing them even if they are not widely or enthusiastically read.)

It is true that in journalism school, we teach that significance is also an important news value, and any reporter or editor would say the same. But the stories that are easiest to launch in newsrooms are those that have a combination of news values, so a significant story might struggle for an assignment editor’s love if it does not also have other elements such as novelty, conflict and local relevance.

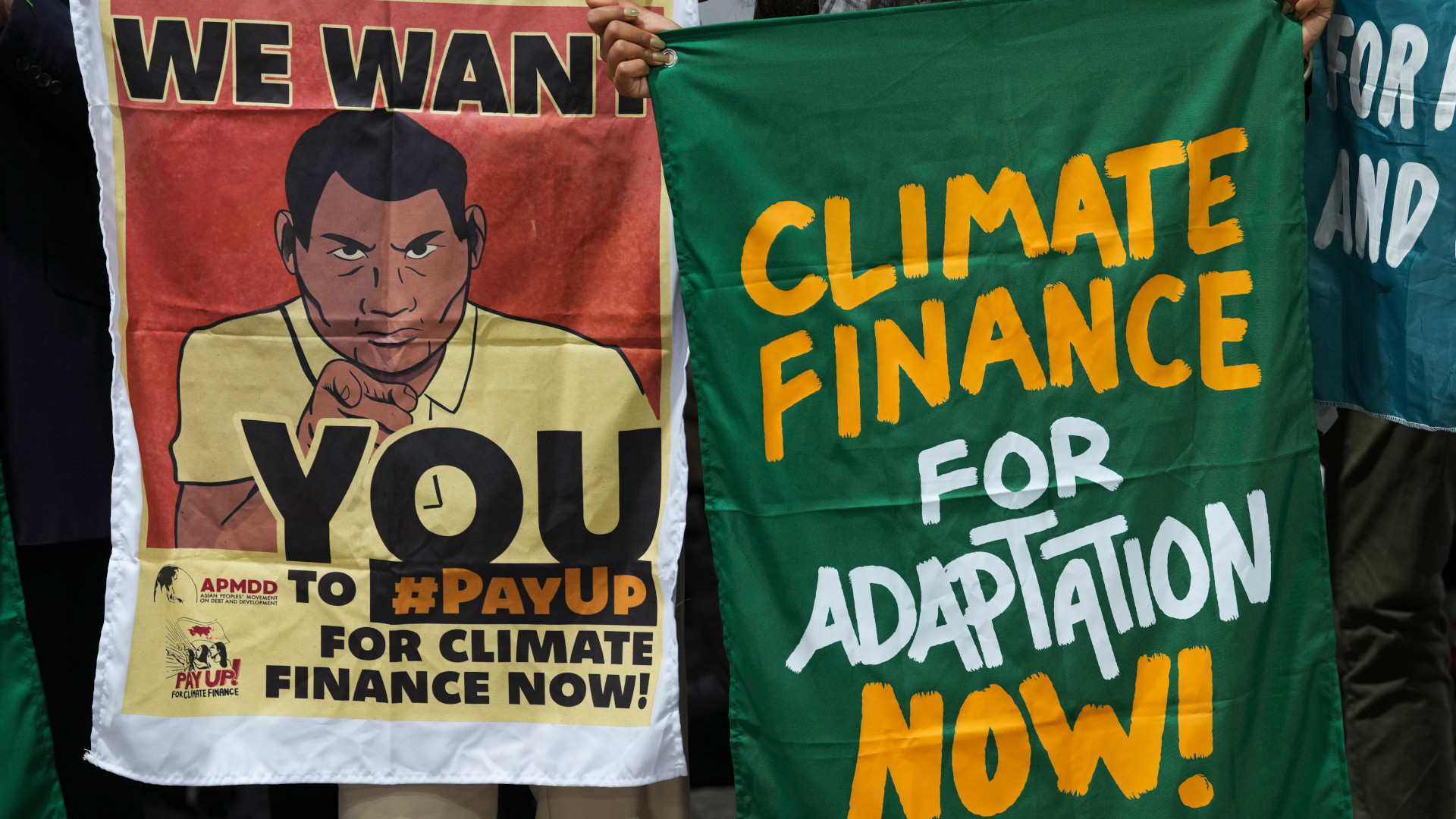

That’s why when Greta Thunberg comes to town, or when school children skip school to support her, journalists jump on the “hook” to talk about climate change. It isn’t just significant. It is novel and it has conflict. Just look at the way she dressed down those politicians at the UN!

But once Thunberg is gone, journalists will again struggle to get attention for climate change stories unless at least one of the leaders says something startling or new or attempts a roundhouse rhetorical punch in a debate.

Photo: Shutterstock, by Daniele COSSU

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.