There was little surprise when the Assembly of First Nations, at its Special Chiefs Assembly in early May, called on the government of Canada to amend Bill C-45, the Cannabis Act. The chiefs sought to prevent provincial regulations from applying on reserves and to allow First Nations to share in the revenue that will be generated by legalizing the production and distribution of cannabis. The move followed recommendations from the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples to delay the implementation of the legislation until Indigenous peoples have been properly consulted.

What was much more surprising was the decision of the Trudeau government to exclude Indigenous governments from the cannabis regime in the first place.

As recent Senate hearings have shown, First Nations, Inuit and Métis leaders have presented compelling testimony that they were left out of the engagement and deliberation on the legislation, both on the important and related public health issues and on how the laws governing cannabis will be administered in the future. This assertion seems to have been validated by the Minister of Health when, in response to a question from Senator Scott Tannas, she was unable to state even one change the government had made to its draft legislation as a result of engagement with Indigenous peoples.

Yet Bill C-45 and the new treatment of cannabis in Canada represent a significant opportunity to demonstrate how a renewed relationship with Indigenous peoples might actually work. This case can show how Canadian laws of general application can be reconciled with Indigenous governments’ jurisdiction in, as the Prime Minister has repeated, “building a true nation-to-nation, Inuit-Crown, and government-to-government relationship with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada.”

In fact, the first of the government’s own Principles respecting the Government of Canada’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples reads as follows: “The Government of Canada recognizes that all relations with Indigenous peoples need to be based on the recognition and implementation of their right to self-determination, including the inherent right of self-government.”

In Budget 2018, the government further recognized “the important role that tax revenues play in supporting self-sufficiency and self-determination for Indigenous governments, [and] the Government of Canada is committed to continuing to negotiate direct taxation arrangements with Indigenous governments.”

The exclusion of Indigenous governments from the proposed cannabis regime seems entirely incongruous with these statements.

At the same time, there are existing paths forward through which this exclusion could, and can, be rectified. In the case of First Nations, the First Nations Fiscal Management Act has already created a statutory basis that effectively recognizes their jurisdiction in matters associated with taxation and financial management. It also provides the institutional support, through the First Nations Tax Commission and the First Nations Financial Management Board, to administer the regime and support First Nations governments in the exercise of their jurisdiction.

Since the law was enacted and the new agencies were established, First Nations have collected more than $1 billion in taxes (mainly property taxes), and the financial performance of over 100 First Nations has been certified by the Financial Management Board as meeting a high objective standard. In addition, since the issuance of the first debenture in 2014, 41 First Nations have raised $376 million in the global financial markets to finance infrastructure, housing and other community projects through the First Nations Finance Authority — another institution created under the Fiscal Management Act. The new system is proven and credible.

The First Nations Fiscal Management Act could be amended to recognize First Nations’ law-making authority to levy taxes on the sale and distribution of cannabis, subject to the administrative framework of the Act and consistent with elements of the provisions currently being contemplated for the Excise Tax Act. Amendments could also recognize First Nations jurisdiction for other regulatory elements, including zoning, local business licensing and enforcement. The legislation would continue to be “opt-in”: First Nations could elect to sign on as a way of exercising their jurisdiction.

Recognizing First Nations jurisdiction to tax and regulate cannabis would allow First Nations to ensure an orderly transition to the legalization of a product that, as many have stated, could affect already vulnerable people and communities. It would also help prevent the development of a grey market for the sale of cannabis, like the current trade in tobacco.

And it would also demonstrate that the government is serious about a renewed relationship with Indigenous peoples, including a new fiscal relationship with Indigenous governments. These relationships, by definition, require a modern tax regime, appropriate revenue sharing and Canada’s recognition of First Nations jurisdiction in matters that affect First Nations communities and people.

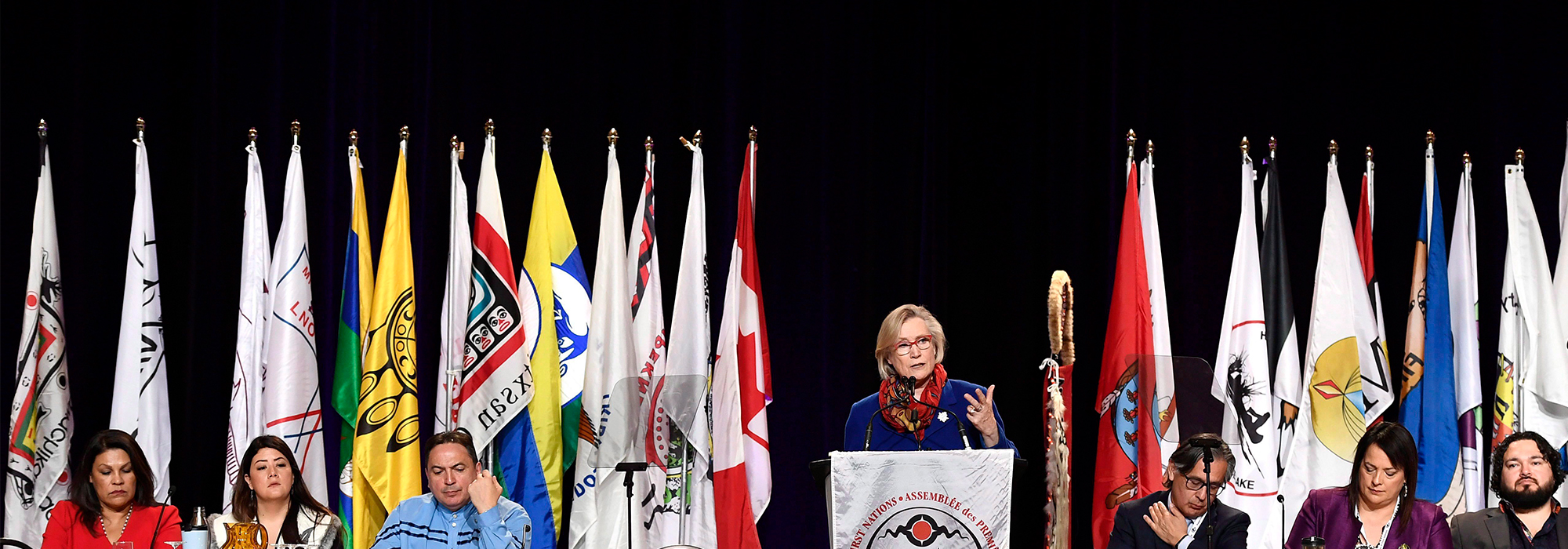

Photo: OTTAWA – Alberta regional chief Marlene Poitras, left, interim Yukon regional chief Kluane Adamek, and National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations Perry Bellegarde, along with co-chairs Harold Tarbell, Racelle Kooy, and Tim Catcheway, listen as Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett, centre, speaks during the AFN Special Chiefs Assembly on May 1, 2018. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.