Rebalancing the relationship between Canada’s Indigenous peoples and the rest of the population is one of the most difficult public policy challenges of our time. Reconciliation will involve many costly and difficult public policy initiatives. The level of public support necessary will require a journalism that goes beyond crisis reporting to challenge the long held images and stereotypes of Indigenous peoples and probe more deeply into the root causes of despair in First Nations. Our examination of coverage from 2006 to 2015 in eight major daily newspapers identified more than 30,000 stories that referred to issues relevant to Indigenous individuals and communities. For the period between 2014 and 2015, we located nearly 2,500 articles dealing with murdered and missing Indigenous women (MMIW) for a more in-depth analysis as well as broader Indigenous issues.

While thousands of articles are published on the topic each year, there are significant gaps and distortions in the coverage. If the mainstream media are to give Canadians a deeper insight into, and understanding of, Indigenous affairs as well as the causes underlying the authorities’ slow response to the issue of the murdered and missing Indigenous women, a stronger commitment of resources and attention will be required.

In terms of all the coverage from the decade-long sample (2006 to 2015), an average of fewer than 11 articles per day across the eight print dailies we examined mentioned Indigenous issues (table 1). This means each paper published an average of slightly more than 1 article per day, which is clearly inadequate.

Readers could expect to find a front-page story on First Nations’ issues in any newspaper at most once a week, suggesting an institutional lack of interest. The way Indigenous issues are reported by the mainstream Canadian media is what we call a “spotlight phenomenon,” meaning that the media presents brief intensive coverage of Indigenous issues (i.e., demonstrations, occupations, suicides, the murdered and missing Indigenous women, unsettled resource claims, police incompetence), which is then followed by a reporting void. However, there are indications that Canada’s media culture has begun to change.

Among our major findings were the following:

- The coverage of the Tina Fontaine case transcended ethnic stereotypes and engendered a broader human response from the national media. Personalizing her story became one of the ways that the national media transformed a tragic news story into a national event that moved Canadians.

- The issues surrounding the murdered and missing Indigenous women, including the call for a national inquiry, were the most heavily covered Indigenous stories in our 2014-15 sample of nine major daily newspapers.

- While Indigenous voices were present in more than half of the stories we examined, it is not clear that the articles were consistently framed in terms that would communicate First Nations perspectives effectively to non-Indigenous audiences.

- There was considerable emphasis on Canada’s lack of response to the issue of the murdered and missing Indigenous women, and on the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s (RCMP) perceived ineffectiveness in bringing closure and justice to the families of women who had been murdered or had gone missing.

- While nearly a third of the coverage of the murdered and missing Indigenous women focused on straight-forward reporting of events, a high proportion included a reference to the moral or ethical issues involved in government policies or a lack thereof, with calls for a public inquiry gaining most attention.

- The First Nations media often presented racism and colonialism as the causes of the issues facing Indigenous people today. These media sources were also much more assertive than the mainstream media in their insistence that what was needed was not only an inquiry into the murdered and missing Indigenous women, but also better protection for women and an overhaul of social services.

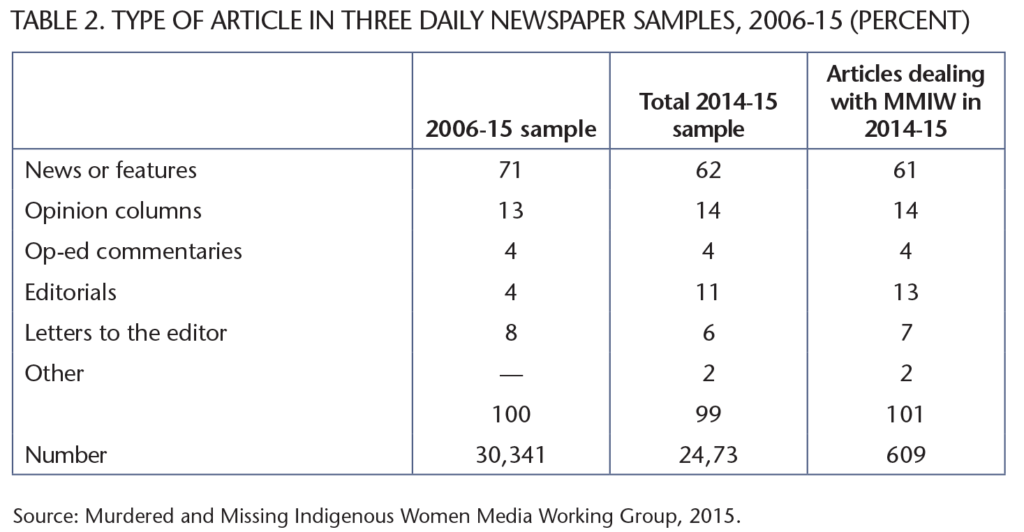

In general, our newspaper sample provides an accurate overview of the mix of the types of articles in the daily newspapers, as shown in table 2. Note that commentaries of various kinds made up nearly 40 percent of the items dealing with the murdered and missing Indigenous women. These articles tend to shape perspectives in the news and determine the overall narratives.

Our study revealed two critical turning points in the news coverage. The first was the 2014 release of the RCMP report on murdered and missing Indigenous women, which was a direct response to the Native Women’s Association of Canada’s 2010 empirical study on 582 murdered and missing women that exposed, for the first time, the high number of Indigenous women who had been murdered or were missing.

The second watershed moment was the intense media coverage of the disappearance and murder of Tina Fontaine, a young northern Manitoba woman, who disappeared after leaving her home in the Sagkeeng Reserve to look for her mother in Winnipeg. This heartbreaking story captured the attention of many Canadian and foreign journalists and became a prominent news story in the mainstream media. The personalization of her story transformed the tragedy of the murdered and missing Indigenous women into a national news story.

All news reporting is framed for the reader because it enables audiences to process and make sense of what is being reported. While modern journalism relies on filters for clarity and selection, these filters also tend to reflect the “conventional wisdom” of society, as interpreted by news organizations. The capacity to be both the gatekeeper and framer of the public agenda, even in the digital era, makes mainstream reporting a powerful instrument of control.

As far as we’ve been able to tell, there are no journalists who are full-time specialists in Indigenous affairs, although the number of Indigenous journalists is increasing. With the possible recent exception of the Globe and Mail and CBC.ca, mainstream news coverage of Indigenous issues suffers in terms of both quality and sophistication when there are so few journalists who have in-depth knowledge of Indigenous communities, values and cultures. Given the importance of reconciliation, this is counterproductive, and it is largely correctable.

There are few journalists who have in-depth knowledge of Indigenous communities, values, and cultures.

Recently CBC.ca and the Globe and Mail have made a public commitment to provide in-depth reporting on the crisis of the murdered and missing Indigenous women. They have played an important role in changing the media narrative about the marginalization of Indigenous women and the failure of the police to protect the rights of the murdered and missing Indigenous women as they would non-Indigenous women. The Toronto Star, Canada’s largest circulation newspaper, has also begun to address the issue more seriously. Even in an era when the major news organizations’ influence is waning, their decisions by to focus on the issue on a continuing basis are critical. Meanwhile, it is notable that Vice Canada, a relatively new digital media outlet, has made the reporting of Indigenous issues a priority.

We found that the Indigenous news sources, when compared with the mainstream media, were optimistic in their reporting of issues, and they had a strong focus on mobilizing for change. Despite limited resources, they offered more suggestions for repairing the broken relationship between the federal or provincial governments and First Nations than the mainstream news outlets. Even in articles that were not opinion-based, the Indigenous media placed blame squarely on the government and police for their lack of effort and attention to the issue of the murdered and missing Indigenous women. They also covered the root causes of the issue more frequently.

One major reason that the issue of murdered and missing Indigenous women did garner increased coverage by the mainstream media is that social movements such as Idle No More and the Native Women’s Association were able to use social media strategically. Their mobilizing efforts have forced the issue from the margins, where it had been relegated for too long. Canadians are still struggling to come to terms with the distorting effects of the spotlight phenomenon, where they are drowned in information when issues spike and then face a skimpy diet of one article a day for the rest of the year. Canada’s media culture must do better.

Canadian journalism has not ignored Indigenous issues, and it has produced some notable coverage. However, when the spotlight moves on, the issue drops off the media (and the public) agenda until the next protest or report.

Although daily newspapers have covered Indigenous issues extensively, news organizations are being called upon to reach a higher standard. As Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner Marie Wilson put it when she spoke to Ryerson’s School of Journalism, “Journalists must embrace their role as educators when reporting on Indigenous issues and recognize how their work shapes perceptions.” Because of the ongoing importance of reconciliation for Canadian society, there needs to be an extraordinary effort to keep it on the public agenda and to promote public understanding.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.