Community members from Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek-Gull Bay First Nation (KZA) stood in silence around the crackling fire, while one of its leaders sang a haunting, beautiful prayer of thanks in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe). After some time, two elders began a tobacco teaching for the children and guests in the community. From the edge of crowd, I looked around to make sure my team of five journalism students were capturing the scene accurately. Were they in the right position for good wide and medium visual shots? How about the team that was recording audio – were they close enough to get clean sound?

After some time, an elder started giving small handfuls of tobacco to each community member to throw into the fire as part of the prayer. Suddenly, he turned to one of my students, arm outstretched. I cringed reflexively. Was she going to take it? Before I could draw another breath, the student closed her hand around his, took the tobacco and threw it onto the flames.

For generations, journalists in North America have been trained to bear witness using detached, arm’s-length reporting. Keeping a distance is considered necessary in order to maintain “objectivity” – one of the cornerstones of traditional journalism. That concept of objectivity was what made me catch my breath when I saw my student actually participating in the story she was supposed to be reporting on. Long after that experience, an elder explained to me that the gesture of including the students was meant to communicate that the community honoured and respected the relationship we had built with them; it was a way of showing us we were welcome. This was just one of the many moments that challenged us to think differently over the course of a research project I was leading on journalism education and reconciliation at Concordia University.

The project involved traveling with a group of five undergraduate journalism students to report on a story in an Indigenous community in Northern Ontario. Later in the project, a graduate student would join our ranks. The first of three trips to Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek-Gull Bay First Nation (KZA) was in the fall of 2018. The community is located about 200 kilometres north of Thunder Bay, on the western shores of Lake Nipigon. Initially, the idea was for the students to learn more about reporting in a First Nation community by focusing on a good news story about climate leadership.

Ultimately, it would turn into a two-year project with the purpose of exploring a slower, more contextual approach to teaching non-Indigenous journalism students how to practise their craft in an Indigenous setting. The experience was humbling, both for myself and for my students, as we realized just how much there was to learn.

“Most of what I learned about Indigenous history and culture dated back to elementary school,” said Lauren Beauchamp, one of the students who participated in the project. “We barely scratched the surface of these critically important subjects throughout my years of schooling, and needless to say, I had never been to a reserve.”

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) had released its final reports and findings. In its summary report, the commissioners included a section on media and reconciliation, noting that for generations, coverage of Indigenous issues has tended towards racist depictions and negative stereotypes. Change has been slow, and requires action on many different levels, including the hiring of more Indigenous reporters, news managers and journalism educators.

Change also requires non-Indigenous journalists to educate themselves, not only about the cumulative impact of colonial narratives dominating news coverage for more than 125 years, but also on the diverse histories and cultures of First Nation, Métis and Inuit communities. Journalism departments have a role to play, as outlined in the TRC’s Call to Action 86.

During the organization of the first group trip to KZA, the students were excited to leave our classroom in Montreal and immerse themselves in a real field reporting situation. Each member of the team set about cultivating the appropriate mindset for responding to Call to Action 86 in a meaningful way, especially since the end result was supposed to be a positive story of climate action. However, as we spent more time walking the land and listening to people in the community, we realized it would not be so simple. The good news was actually rooted in deep pain and devastation from the past.

The community was building a solar-powered microgrid that would use a combination of battery energy storage and solar panels in order to reduce its reliance on diesel. It was the first undertaking of its kind in Canada, and an impressive example of the work being done to find clean alternatives to diesel in the North.

With the permission of chief and council, and members of the community, we worked to document the story of climate leadership in KZA. The project involved building relationships between the students and key members of the community, and taking our time both in KZA and upon our return in order to craft the most accurate and contextual story possible.

Over the course of our reporting trips, we found ourselves abandoning certain ways of operating that, while considered normal journalistic practices, have also been shaped by colonialism and an individualistic, top-down approach – for example, booking interviews with short lead times, and not necessarily keeping in contact with interview subjects after covering their stories. After visiting KZA, we found ourselves reaching out to certain members of the community nearly every week as we edited the project, to gather more background and context, and to continue checking facts. We kept up the relationship after all the reporting trips were finished, which is something that doesn’t happen all that often in the typical newsroom where beat reporters are increasingly rare.

In order to keep within a small budget and ensure mobility, interviews, photos and video footage was shot using smartphones, a GoPro and a few DSLR cameras. Student journalists were trained and coached in the tools and techniques of mobile and “solutions-oriented reporting” in order to share the story of KZA responsibly, keeping the history of negative representation of Indigenous issues at the forefront of our minds. The focus on climate leadership in KZA was specifically chosen in the hopes that it would inform and attract a broader audience.

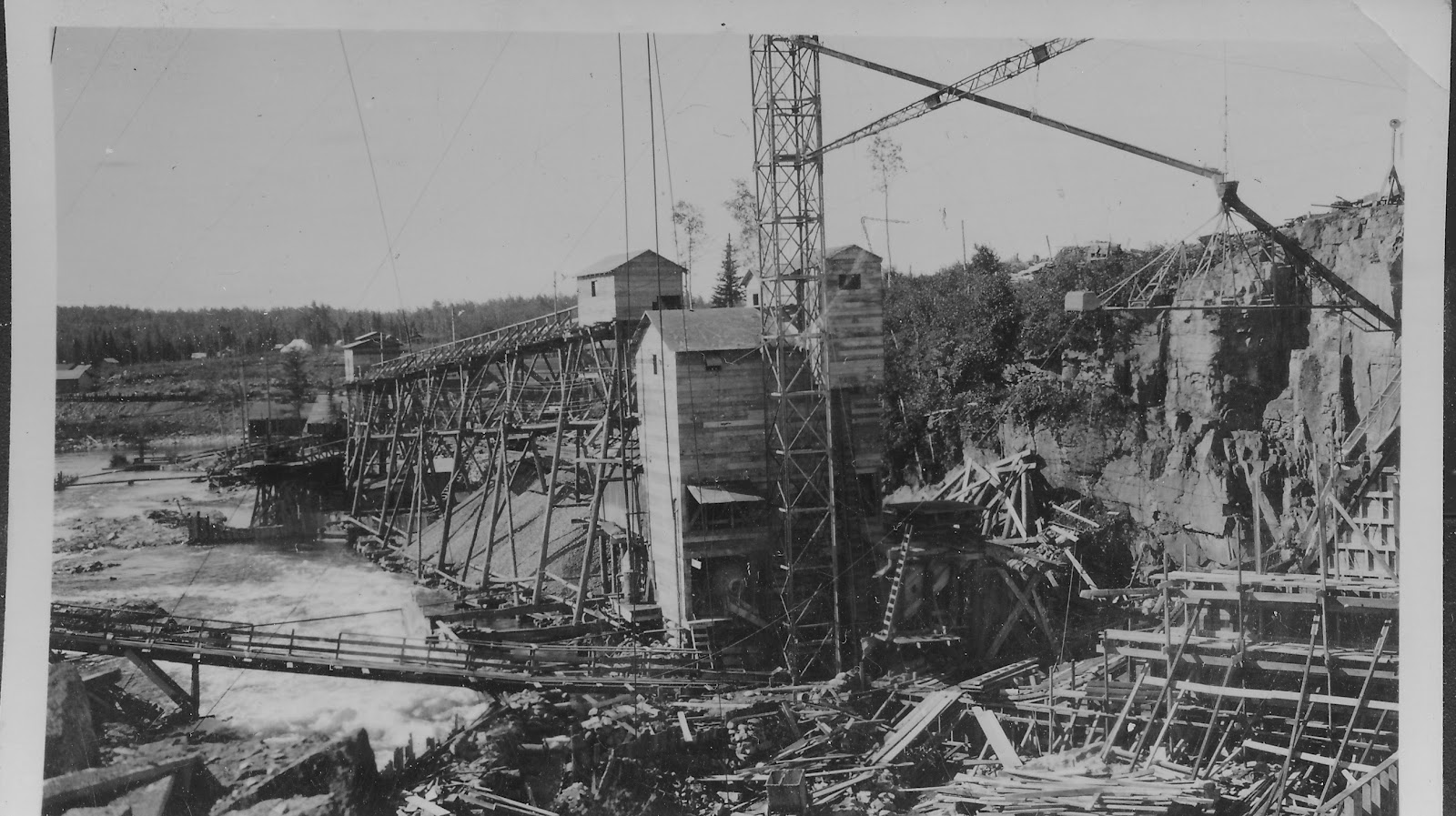

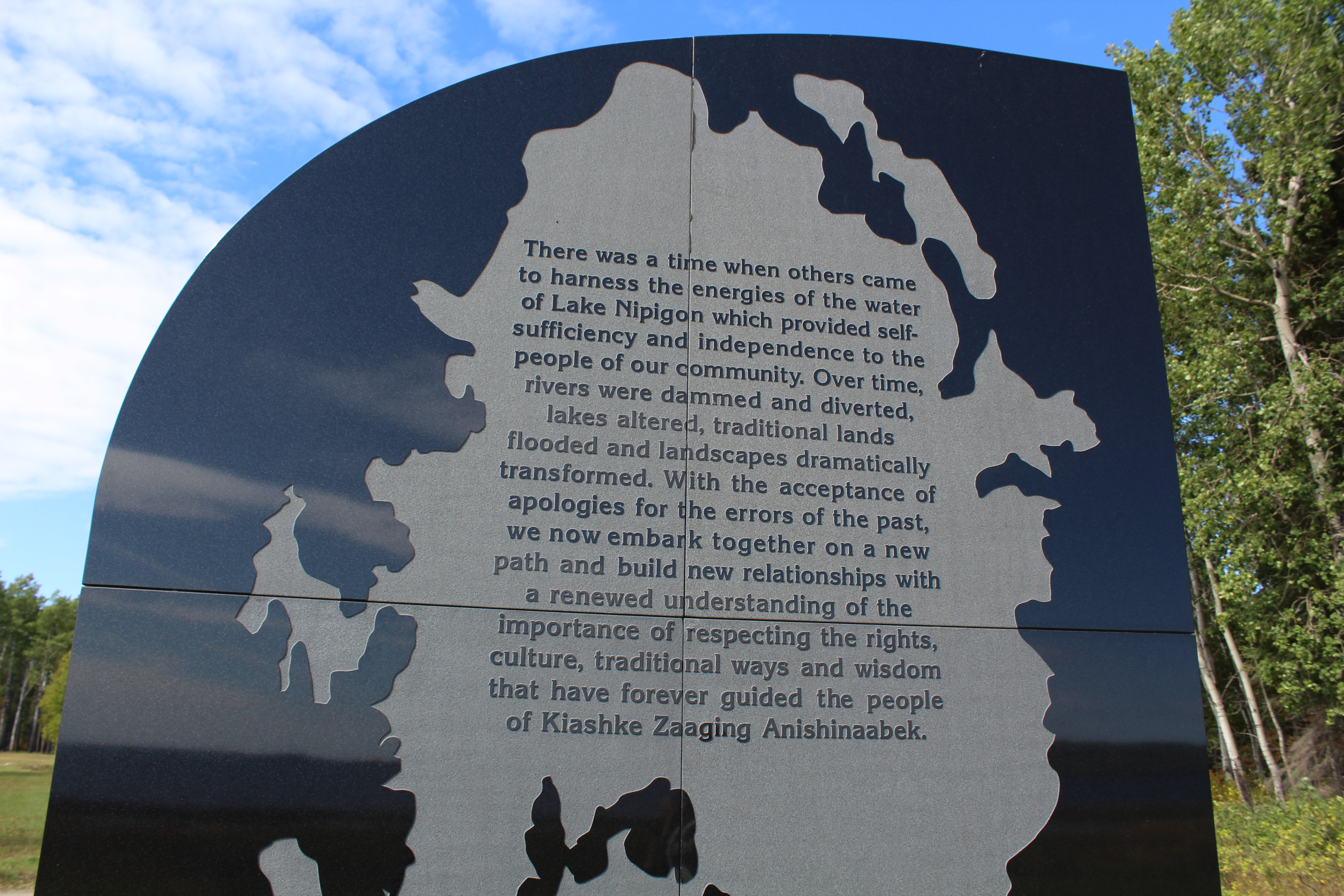

The construction of the microgrid was what brought us to KZA, but the story we would end up sharing was multi-layered and rooted in colonialism and environmental racism. Between 1918 and the 1950s, several hydro dams were built on the Nipigon River, the closest of which at Pine Portage was some 90 kilometers southeast of the community. The construction of the Cameron Falls Dam alone would raise water levels in the river by 23 metres. Between the Cameron Falls Dam, the Alexander Dam, the Pine Portage Dam and the Ogoki Diversion, the impact on KZA was catastrophic and repeatedly flooded the land and buildings throughout the community for years.

The shoreline adjacent to KZA ultimately eroded by more than 60 metres. Burial grounds that were located close to the water came apart, and for weeks at a time, coffins dislodged and broke apart in the lake. The people of KZA spent months retrieving and re-burying the remains of their friends and loved ones. KZA was neither told of the construction nor warned of its effects and would only find out years later that the damage had been caused by the construction of several hydro-electric projects run by the power authority of Ontario.

The process of building trust with community members in this context required us to use a different playbook than what is typically taught in journalism school. Building time into a reporting schedule to get to know someone or have tea before an interview is not typical, but in KZA we were taught that if we wanted to share this story, we would have to do things differently. Those lessons were learned early on in the process and we carried them with us for the duration.

The dams would eventually provide power to approximately 290,000 homes in Ontario – but none in the tiny community of KZA, where only about 300 people live year-round. Connecting KZA to the provincial grid was not economically feasible, according to Ontario’s Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO).

For decades, the community was forced to power homes and buildings using diesel generators despite a slew of negative environmental, social and economic impacts. These included increased greenhouse gas emissions, noisy and disruptive generators operating around the clock, and the constant threat of fuel tank leaks into soil and groundwater.

Ontario Power Generation (OPG) offered an official apology to the people of KZA in 2014 for the damage caused by the projects undertaken by its institutional predecessor, the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario. The apology included plans for an historic partnership between KZA and OPG focused on building a clean energy source in the community, and ultimately resulted in the construction and completion of the microgrid in 2019.

The diesel generators were shut off in August 2019 for the first time in almost 60 years, during the official launch of the microgrid. Silence suddenly filled the air.

Minutes later, six eagles appeared, flying overhead in sweeping circles. A good omen, according to Mashkawiziiwin Energy Projects Coordinator AJ Esquega: “You can see the birds are already thanking us.”

The community microgrid uses more than 1,000 solar panels, over 80 battery modules and automated control technology to offset diesel consumption year-round. When the sun is shining, the community can use solar power for all of its needs. If clouds roll in, the battery system activates immediately in order to meet demand without a fluctuation in supply.

KZA, not the provincial utility, will own the microgrid, and its development corporation, Ma’iingan Development Inc., will operate and maintain it. As KZA Chief Wilfred King reminded us, reconciliation also includes economic reconciliation and the opportunity to extricate the community from poverty.

The Concordia journalism project ultimately involved six students and hundreds of hours of writing and editing. The result was a multimedia project called “From shore to sky: a reconciliation story,” created in collaboration with the people of KZA, students and CTV Montreal as a media partner.

Throughout the process, we were constantly faced with moments to scrutinize our practice in the context of reporting in Indigenous communities. In one case, I remember a student being worried about offering tobacco and water to some of our interviewees. In school, he had been taught to never pay a source. Giving “gifts” ran counter to everything he had learned so far. Yet in this context, the exchange was not considered a gift, rather, offering tobacco was appropriate, since we were asking for assistance to understand and share community stories. The acceptance of the offering in turn signaled a willingness to help us by sharing knowledge and perspective. It was also important to internalize that we were sharing this story and not telling it, since the story itself was not ours to tell.

The overall experience resulted in a meaningful opportunity for me, as a non-Indigenous journalism educator, to transform my own perception and understanding of journalism education through the lens of Call to Action 86.

Journalism schools must do better when it comes to training and education on Indigenous issues, having fallen short for so long. When the TRC’s final report was released five years ago, very few schools included in-depth instruction on Indigenous affairs. Since then, more schools have introduced courses aimed at the decolonization of journalism education and have developed innovative projects of varying size and scope, including several that take students out of the classroom and directly into Indigenous communities.

Reconciliation was described by the TRC as a “process of truth and healing” and a renewal of “relationships on a basis of inclusion, mutual understanding, and respect.” Call to Action 86 is an opportunity for journalism educators to explore how teaching and learning can be centred on building trust and lasting partnerships with Indigenous communities.

“Before the trip I had not been aware of the extent to which Indigenous communities had been left out of the provincial energy plan, only included when the government needed their waters or land. In so many ways, this is exactly where journalism education needs to go,” said Concordia student Luca Caruso-Moro.

“Students need to be encouraged to expand themselves further, embed themselves within communities, and become engaged with Indigenous issues. This has been a profound learning experience in compassion and respect.”

Main Photo: Concordia University research team interviews KZA Councillor Kevin King in front of the microgrid site in October 2018. Photo by Marissa Ramnanan