There is no CEO rant that passionately declares: “I am a Canadian business person. The ideas and the efforts of the people in my company help to create prosperity and well-being for our shareholders, our stakeholders and our fellow Canadians. Yes, we care about the environment. Yes, we care about human rights and social justice. We are business persons. I’m proud of what we do.”

Why don’t CEOs report on the economic wealth and social well-being, and, yes, the problems, too, that their companies create for business and community stakeholders? There are two main reasons: first, CEOs don’t have to do it; and second, no one in the company—not the CFOs, not even the new MBAs—knows how to do it, even if they wanted to.

During the fall of 1998, a year before the anti-World Trade Organization battle-in-Seattle, two years before the World Bank/IMF protests in Prague and almost three years before the civil societies’ spring carnival in Quebec City at the Summit of the Americas and the more tragic events at the G8 gathering in Genoa, two Government of Canada corporate social responsibility/accountability initiatives surfaced in two separate public policy debates. One of these initiatives failed, the other has become law.

The November 1998 House of Commons SubCommittee on the Study of Sports in Canada asked as one of ten performance criteria for receiving federal income tax concessions that each Canadian NHL team show the socioeconomic benefits it would bring to its local community. As we now know, that never happened.

On June 8, 2001, with royal assent to The Financial Consumer Agency Act, Canada’s six largest banks and five largest life insurance companies, because they are federally incorporated entities and have equity in excess of $1 billion, will now have to publish annual “public accountability statements.” The statements will describe each institution’s contributions to the economy and society as well as specific social marketing practices such as funding for local government and voluntary agencies’ community work, small business financing, micro-credit programs, banking services for low-income individuals, and employees’ participation in the community.

During Senate-sponsored hearings on the Task Force Report on the Future of the Canadian Financial Services Sector in September 1998, Senator Catherine Callbeck of PEI pointedly asked each CEO from Canada’s 11 largest financial institutions what would be the content of the annual public accountability statements (PAS) called for by the Task Force Report. None of the CEOs could answer her question. Matthew Barrett, then Chairman and CEO of the Bank of Montreal, replied that a PAS would be a small price to pay if it stopped the Canadian sport of bank bashing. Former Nova Scotia Senator John Stewart commented wryly that public accountability statements would be nothing more than annual corporate boasting statements, and he wisely asked “Why just the banks? Why not public accountability statements for all large Canadian companies?”

So far only seven Canadian organizations voluntarily issue a genre of corporate social responsibility (CSR) report: one major financial institution (Royal Bank Financial Group), two credit unions (VanCity and Metro Credit Union), two oil and gas producing companies (Suncor Energy Inc. and Talisman Energy Inc.), a utility (TransAlta) and a mining company (Inco).

There are large differences in the scope and quality of the information currently provided. VanCity, which is a provincial financial institution, voluntarily pre-empted the impending banking reform legislation and explicitly reported on eight of the nine PAS reporting requirements outlined in Department of Finance’s June 1999 White Paper. (Because VanCity’s Social Report left out economic outputs and focused on two of the three other elements of sustainability, the environment and social impact, the category it did not report on was taxes paid to all levels of government.) If mandatory PAS and voluntary CSR reports are to create a meaningful dialogue with stakeholders, there must be a generally accepted common core of information and a common reporting format.

Ford Motor Company has produced two annual Corporate Citizenship Reports (for 1999 and 2000). Jacques Nasser, Ford’s CEO, argues that becoming a recognized leader in corporate citizenship is critical to Ford’s long-term financial success. Effective corporate citizenship reporting will help a company to retain and recruit skilled employees, to maintain and increase market capacity, to grow shareholder value, and to attract long-term investors. The main non-financial goal of a CSR strategy is to focus the firm on increasing the “social capital” on which our private enterprise system depends. “Social capital” is generally defined as trust among citizens and between citizens and business. As business professors David Leighton and Don Thain have argued (in Making Boards Work, McGraw-Hill Ryerson), the private enterprise system depends on the acceptance and support of the general public, particularly the stakeholders of the business—its employees, customers, creditors, suppliers, communities and governments. “Aggrieved stakeholders eventually reach the limits of their tolerance for those who are contemptuous of or threaten their interests.” When that happens the results are costly regulations that are simply bad for business.

In the UK, Tony Blair’s government has appointed that country’s first Minister for Corporate Social Responsibility. United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, speaking at the January 2001 World Economic Forum in Davos, said the UN will target 1000 major companies to adopt the UN’s nine Global Compact principles by 2002 (see www.unglobalcompact.org). Two of these principles concern human rights, four deal with social justice labour issues and three have to do with the environment.

In Brussels, the European Union Commission has designated the year 2005 as a European Year on Corporate Social Responsibility. “European Campaign 2005” is supported by CSR Europe’s 15 national organizations and the Danish international body, The Copenhagen Centre. Over the next four years, they aim to mobilize half a million business people to implement CSR principles, one of which will surely be annual corporate citizenship accountability.

Canada should not be left behind in this international effort to make corporations more accountable to their communities. So as to strengthen Canada’s ongoing economic, environmental and social well-being and to promote the competitiveness of Canadian business in the 21st century, federal policy should require all corporations receiving more than $1 million in cash flow assistance from all government programs in any year to issue annual corporate citizenship (CC) sustainability reports for the next five years.

More than 300 Canadian corporations receive $1 million a year in federal and provincial Scientific Research and Experimental Development tax credits and financial assistance from federal programs such as Technology Partnerships Canada, the Industrial Research Assistance Program and various other federal and provincial programs designed to increase economic growth and create jobs and wealth. A private company like IBM (Canada) Ltd., which has received many millions of dollars in both federal and Ontario government assistance for its Markham, Ontario research facility, would in the future be obliged to issue an annual CC sustainability report. So would publicly-owned Bombardier Inc. whose American customers recently received more than $3 billion in Export Development Corporation low-interest loans.

Enlightened industrialists will understand that an annual CC sustainability report is not just more red tape. Finance Minister Paul Martin recently warned the high-technology industry’s chief lobby group, the Canadian Advanced Technology Alliance, that before the federal government will offer it more public policy rewards the general public has to buy into the idea that the tech industry benefits everyone. Effective CC sustainability reports from large high-technology firms would be one answer to the finance minister’s challenge. Given widespread public mistrust of large corporations, similar considerations are relevant in most other industries.

Because of their nature as institutions that advance the common good, the 15 or so Crown corporations with equity in excess of $100 million should also produce annual CC sustainability reports. And yet two of the federal government’s most important financial services Crowns, the Business Development Bank and the Export Development Corporation, are exempt from the PAS requirements brought in by the new financial services legislation—even though EDC has nearly $1 billion in equity, which is the dividing line for private institutions. The Crowns’ CEOs repeatedly say they will make their operations more transparent to the general public, their stakeholders and critics in civil society. One obvious way to do that would be to issue annual CC sustainability reports.

Today, CEOs are likely to run across customers and competitors, both in Canada and in international markets, who prepare annual sustainability reports. It’s no longer just The Body Shop and Ben and Jerry’s Ice Cream that issue annual CSR reports. Over 60 major B2B and B2C corporations, in over a dozen countries, use Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) sustainability reporting guidelines as their triple-bottom-line sustainability reporting framework. For instance, Agilent Technologies, Ford Motor, General Motors, and Procter & Gamble are four of the 12 American companies issuing GRI sustainability reports. British Airlines, Co-operative Banks, Shell, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, Henkel Chemicals, Electrolux and Aéroport de Paris are seven of the 31 European Union GRI-firms; Fuji, Xerox, Konica, NEC Corporation and Nissan are four of the nine Japanese GRI-firms, while Inco, Suncor Energy, TransAlta and VanCity Credit Union are the four Canadian GRI companies.

Established in late 1997, Boston-based GRI International is a multi-stakeholder, non-profit organization currently in the process of electing its first board of directors, mostly from international NGO groups. Its founding 17-member steering committee included two for-profit companies, General Motors and Sweden’s 100-year old ITT Flygt, a worldwide pumps/generator manufacturer. The Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants was one of 15 not-for-profit members.

A GRI sustainability report has six parts. It begins with a CEO statement in which the CEO reports on sustainability successes and failures and identifies major challenges for the organization and its business sector in integrating responsibilities for financial performance with the implications of these issues on future business strategy. Next comes a profile of the reporting organization and the scope of the report, then an executive summary with key economic, environmental and social performance indicators. The most demanding GRI section very likely is “vision and strategy,” in which, possibly for the very first time, senior management is asked to set out its vision of the company’s future and discuss how that vision integrates economic, environment and social performance.

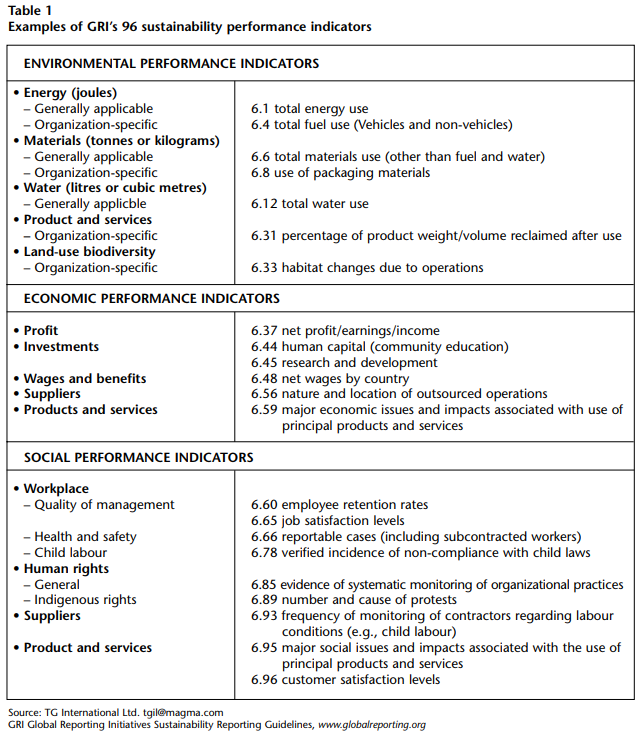

The “policies, organizations and management systems” section of the report has 14 performance indicators concerning the governance structure and the management systems in place to implement its vision. Central to this section is a discussion of stakeholder engagement. Performance indicator number 5.12, for example, asks for approaches to and frequency of stakeholder consultations, be it by surveys, focus groups, written communications and so on. Table 1 presents a sample of GRI’s 96 performance indicators, of which 36 have to do with the environment, 23 with the economy and 37 with society at large. Surprising as it may be, there is only one performance indicator (number 6.53) concerning “philanthropy/charitable donations.” There clearly is much more to good 21st-century corporate citizenship than community giving and employee volunteerism.

In its 2000 Corporate Citizenship Report, Ford Motor Company wrote that “The purpose of a GRI report is to provide sufficient information so that readers can make an informed assessment of a company’s performance. GRI reporting also helps us to review our own performance.” Will CC sustainability reports become corporate boasting reports, as former Senator Stewart predicted? Without SEC-like monitoring, probably. Simon Zadek, chair of the London-based Institute of Social and Ethical AccountAbility, argues that glossy approaches to social reporting are rapidly becoming a business liability that attract criticism rather than applause, while PriceWaterhouse Coopers emphasizes that sustainability reports must tell the people what they want to know. There needs to be consistency in the type of information disclosed and the reporting format that is used. With the ease of comparability that it provides, the Internet has created a fundamental shift in the way companies must interact with their critics.

The GRI content requirements obviously require a considerable amount of work. A full, triple-bottom-line, sustainability GRI report does not have to be done all in one year, however. It may take several years to get it right. In Annex 2 of the 63-page GRI Guidelines, directions are provided on how an organization may take the first of many steps on the road to a full, triple-bottom-line, sustainability report. GRI’s stated goal is to elevate sustainability reporting practices to a level equivalent to corporate financial reporting.

Critics of any public policy requiring CSR reporting will be quick to label it as a liberal plot against capitalism, heresy against the laisser-faire, Friedmanite doctrines that have become so powerful in the last two decades, and as another unnecessary intrusion by government into the boardrooms of the nation. Not at all. As a corollary to his proposition that a company’s first responsibility to society is to earn a profit, Peter F. Drucker has written that management has a responsibility to take actions that promote the common good so as to offset the deep-seated hostilities against profits. CSR reporting will spawn new management actions for promoting the common good.

One such practice has already begun. GRI reporting firms’ managers and their employees meet face-to-face and talk with stakeholders about their expectations and needs. Another socially helpful and altogether too rare event often occurs at these meetings: stakeholders with conflicting interests get to talk to one another about their differences while management listens.

Consider this new CC sustainability management idea: before each meeting every member of the corporate board would visit several civil society groups’ websites—an exercise that likely would prove to be a surprising, maddening and enlightening learning experience in Responsible Capitalism 101. Imagine the payoff to corporate governance. Directors would be much better able to assess the impact of management actions on the common good.

In fact, CC sustainability reporting is good Friedmanite economics. Milton Friedman wrote that a CEO has a direct responsibility to make as much money as possible for the company’s owners while conforming to the basic rules of society, as embodied both in law and customary ethics. Corporations currently are seen by civil society groups everywhere as not conforming to the basic rules of society and ethical custom. If CC sustainability reporting improves the public’s image of large corporations, they may well be able to make more profits than they can now. Some day a company’s social performance may even become a key political and legal ingredient for issuing an organization’s license to operate.

Seventy years ago, senior management resented and resisted the new laws that required publicly-owned corporations to have external professional accountants audit their annual financial statements and to make their findings public. With hindsight, we know that the mandatory public policy for audited financial statements was wise 20th-century legislation. In just the same way, it will be wise 21st-century public policy to instigate selective mandatory CC sustainability reporting.

Attending to stakeholders’ legitimate social concerns should in the long run benefit all parties, including investors. Most businesses do contribute to the economic wealth and social wellbeing of their shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, business partners, community and country. Most business people certainly believe they do. If that’s the case, why not say so in a systematic, disciplined way on a regular basis? Given the rising tide of protest from civil-society groups, CEOs’ silence is not a viable long-term growth strategy for Canadian business and their communities. A Canadian public policy requiring selective CC sustainability reporting will encourage CEOs to express their corporation’s long-term sustainability vision and to report the progress made toward implementing it each year. If effective CC sustainability reporting does help grow “social capital,” that will be good for all Canadians, business included.

Photo: Shutterstock