It would be easy to surmise that in the struggle to define 21st-century Western society, the forces of secularism are winning. As “new atheists” stridently occupy op-ed pages, law and policy seem to target the convictions of traditional religious communities for exclusion. Religious views have become less and less plausible in sectors of cultural influence in contemporary North American society. It would seem that the predictions of secularization theorists are coming true: as societies advance, religion withers; as production and consumption increase, faith decreases; as we become more “enlightened” and democratic, Christian faith looks more and more irrational and less and less tolerable.

Is this the beginning of the end, a kind of secular apocalypse? Should Christians (and other faith communities) in Canada and the United States be digging trenches to mount a last stand, intellectually arming themselves for a culture war?

Let’s consider an alternative reading of the present, one suggested by Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor’s analysis of our “secular age.” What if an increasingly aggressive secularism (coming especially from secular “elites”) is itself a defence measure, a kind of last gasp of a world view that feels frustrated and even threatened by its own failure? Our modern faith in rationality has not delivered on its promises. The utopian dreams of the Enlightenment have not arrived. The supposed universality of reason has not liberated us from persistent inequalities, and the disenchanted cosmos of scientific rationality has bequeathed to us a warmer planet that poses serious questions about human flourishing in the future.

What if secularism is loudest precisely because it is a final cry before it is unveiled as implausible and unsustainable? After all, the emperor shouts loudest about the beauty of his clothing precisely when he least believes it himself.

If something like this were true, we might expect secularism to be most aggressive precisely when it is most vulnerable. In that case, we might do well to listen once again to the perennial wisdom that has endured in communities of faith that have continued to ask the “big questions.” Religious communities have long cultivated habits of cosmic reflection that could benefit us all as we face the challenges of climate change, global warming and the effects of human culture. If we’re losing faith in secular rationality, perhaps that’s an invitation to consider other faiths.

The secularist’s doubt is, in fact, a form of faith. What counts as “temptation” for the nonbeliever is belief. If the believer is haunted by an echoing emptiness, the unbeliever can be equally haunted by a hounding transcendence.

John Updike, who long wandered in the terrain of belief and unbelief, described the visceral experience of doubt in his essay “The Future of Faith”: “It is as if one were suddenly flayed of the skin of habit and herd feeling that customarily enwraps and muffles our deep predicament.” We tend to imagine this as the experience of the believer: the ardently religious naïf who leaves the habits of home wakes up to “reality” at university and feels like he has lost his moorings.

But unbelievers can have the same experience. Secularism has its own habits and herd instinct, which cultivate a confident naturalism. Yet even in our so-called “secular age,” the so-called unbeliever can be caught short by an epiphany of fullness that transcends her categories. (One sees this in the exercise of atheist Barbara Ehrenreich, in her remarkable book Living with a Wild God, trying to make sense of mystical experiences from her youth.) Our disenchanted world views will still find themselves confronted by a stubborn sense of something-more-ness that can’t be squelched. The secularist’s dark night of the soul is the jarring experience of a sleepless night where he finds himself inexplicably asking: “What if I have a soul?”

So what if we approached an increasingly “secularized” society not as the final victory of some Enlightenment myth in which history ends in unbelief, but rather as the final unsustainable part of a long detour we’ve taken in the West? Perhaps the defensive posture of secularism should be seen as an invitation to consider what a postsecular society might look like.

What we might find on the other side is that our confident distinctions between “sacred” and “secular” are not as stable as we might think. If we could look at our current cultural moment through the eyes of Martian anthropologists—trying to get an “outside view” on the world we’re immersed in—we might notice that many supposedly secular movements are characterized by a kind of religious ardour and devotion, not least the environmental movement. Thus McGill University ethicist Margaret Somerville describes what she calls the “secular sacred”: the task of forging a shared, social life in the cosmos continually calls for us to recognize something as sacred, even if we don’t link that to rituals or traditional religious institutions. In this sense, even the secular is haunted.

But in a postsecular conversation we might also notice that the public face of religion looks nothing like what you’d expect if you read only press releases from the New Atheists. While secularism trots out the straw man of a religion that allegedly “poisons everything,” religious believers continue to contribute to our common life, through food banks and homeless shelters, peace initiatives and palliative care centres.

And as shown in the articles in this issue on the environment as seen through the prism of Christian faith, there are religious believers who are passionately concerned about environmental protection, climate change and the stewardship of creation precisely because they believe the cosmos is enchanted by a divine presence. Belief in transcendence is not mutually exclusive with concern for this-worldly realities; to the contrary, it is belief in transcendence that underwrites a sense of the sacredness of creation. As Charles Taylor puts it, the Protestant Reformation unleashed a sanctification of secular life.

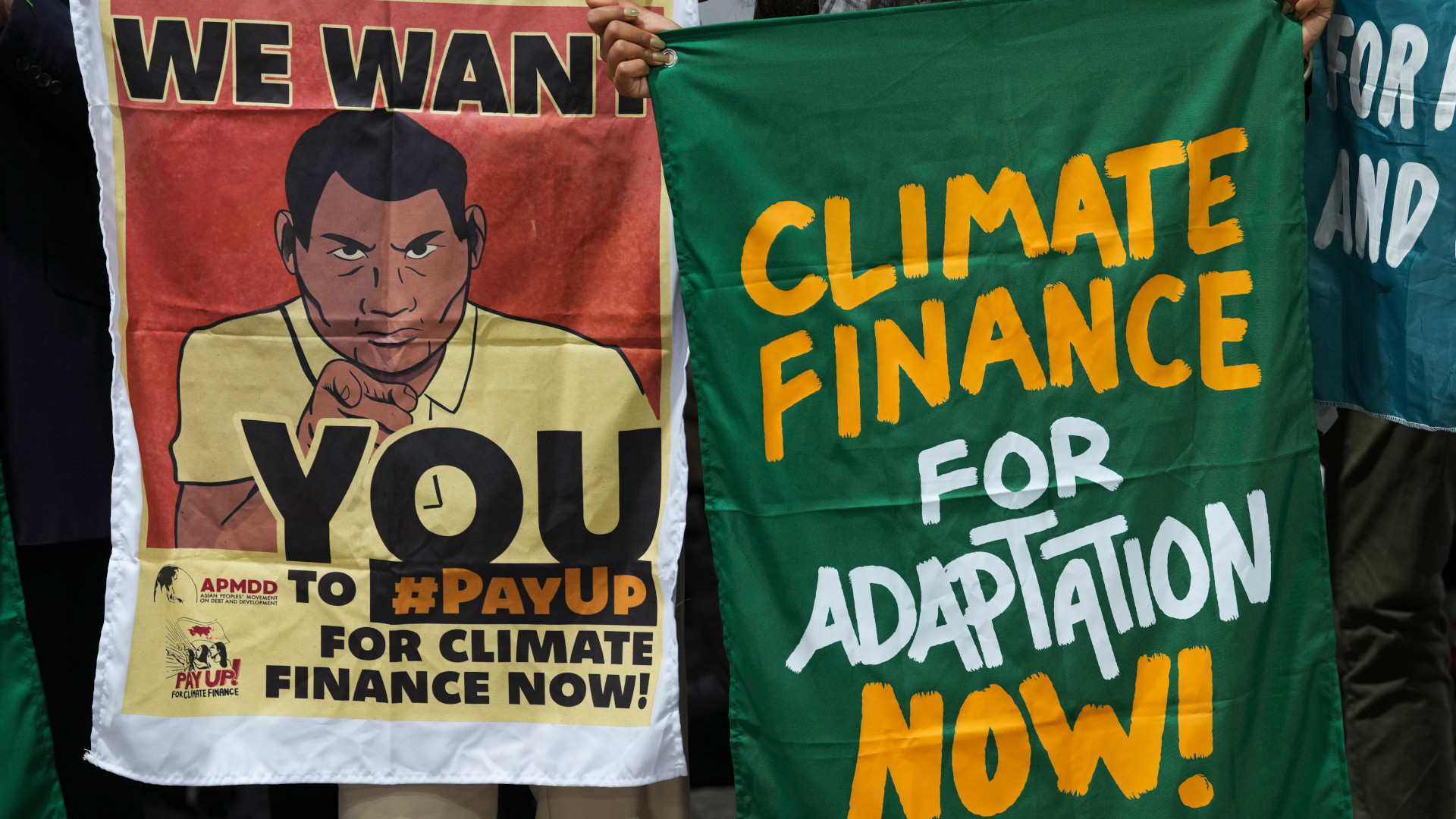

So the old boundaries don’t work anymore. Those concerned about climate change might find some of their best allies in religious communities.

In the heart of Manhattan, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, hangs one of El Greco’s remarkable creations, The Vision of Saint John. Completed around 1614, it looks like it could have been painted in Paris in the early 20th century. Its feel is not only modern but somehow imperceptibly contemporary. It evokes the opening of the Fifth Seal in Revelation 6:9-11; the martyrs who bore faithful witness are given white robes while John (it seems) looks heavenward toward the epiphany of the Lamb. The colours of the painting are themselves a startling revelation of another reality.

But the painting as we view it today is a fragment. The canvas that hangs in the Met doesn’t tell the whole story. In the course of a “restoration” around 1880, the unfinished canvas was trimmed by at least 175 cm. In the name of “improvement,” the scene is truncated by almost half.

And so, in what seems a fitting parable of modernity, the exultant arms of John the Revelator reach upward to—nothing, to the top of the frame, to the edge of the canvas. The martyrs seem to receive gifts from nowhere, and John seems to praise the nonexistent. All of them seem to look for something that is no longer there.

What if our modernist, secularist projects of “improvement” have unwisely severed us from what makes for a flourishing society? What if our policy discussions were haunted by transcendence? While some might rail against myths of what lies beyond the frame, many others might be asking: What is up there?

Photo: Shutterstock

A different version of this essay, “Cracks in the Secular,” appeared in the fall 2014 issue of Comment.