Fixing defence procurement is a common goal of governments. Yet not only have we not seen improvements in this function, many objective measures indicate that over the last decade it has significantly deteriorated. There are two reasons for this inertia. First, to effect real change, clear and unequivocal direction must come from the prime minister. To date, no prime minister has provided this impetus. Second, governments have not taken the time to really understand the impediments to effective and efficient defence procurement. Instead, they have relied on superficial remedies, often advanced by companies whose self-interest trumps the interests of the military or the taxpayer.

Here are the top three impediments to a well-run defence procurement organization, along with three recommendations for solutions.

The first impediment is a lack of clear accountability. For over a decade, I have been a fervent advocate of the need to establish one point of accountability. Quite simply, there is excessive overlap and duplication between the roles of the minister of national defence and the minister of public works and government services. Unless and until one minister is placed in charge of it, defence procurement will never be as efficient and as effective as it could be. As the Canadian Association of Defence and Security Industries recommended in a 2009 report, “Overall accountability for the combined responsibilities of defence equipment and the defence industrial base should reside at the Cabinet level in one Minister.”

I recognize that addressing this governance issue will not solve all the procurement problems, but it is a necessary first step. Among our close allies, Canada stands alone in this regard. In the United States, the secretary of defense is accountable for military procurement. In the United Kingdom, this responsibility falls to the UK secretary of state for defence. In Australia, defence procurement is under the authority of its Defence Materiel Organisation, which is accountable to the minister of defence.

Ironically, instead of clarifying and strengthening accountability, over the past few years we have witnessed a continuing erosion and confusion around accountability. Under the new Defence Procurement Strategy, the Permanent Working Group of Ministers was established, supported by the Permanent Deputy Ministers Governance Committee. Also introduced was the Defence Analytics Institute, consisting of an independent, unaccountable group of outside experts with a mandate to challenge the military’s requirements. In this maze of committees and advisers it will be even more difficult to pinpoint the minister accountable for defence procurement.

The concept of clear accountability should be obvious to most people. After all, it is a basic tenet of any well-run private or public organization. It is supported by past ministers of the Department of National Defence (DND) such as Art Eggleton, Bill Graham and David Pratt. As mentioned above, it also has the support of Canadian industry. Why, then, has there been so much opposition to its implementation?

The fact is that two groups of people will want to maintain the status quo. The first is the bureaucrats and the minister at Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC). Who wouldn’t want to travel to international air shows in Farnborough, England, or in Le Bourget, France? For these people it is much more stimulating and rewarding to be part of billion-dollar programs and announcements than to focus on the purchasing of the more mundane goods and services such as furniture, travel and temporary help. The thought that they would lose this role (although it is not necessarily true) drives them to reject the concept of a single defence procurement organization under one minister.

The second cohort that fights this proposal consists of those companies that put their self-interest ahead of the interests of the military or the taxpayer. Their priority is to influence the government’s awarding of defence contracts. To do so, they need to maximize their points of entry into the defence procurement process. If you want to influence a decision to favour your client, you want to be able to speak to a minister or senior officials involved in the process. If there are two or three involved, you have a greater chance of meeting with one of them. If there is only one minister accountable, then all your eggs are in one basket.

Irrespective of the governance model selected (my preference is for accountability to reside with the defence minister), the requisite legislative and organizational changes can be implemented within one year.

Recommendation 1: Establish a new defence procurement organization headed by one minister.

The benefits of creating a single procurement organization go beyond strengthening accountability. First, the process would also be streamlined. At the present time, the process moves only as fast as the slower of the two organizations permits. As ministers, deputy ministers or even assistant deputy ministers change, the process stops for new briefings. With two departments involved, twice as many potential interruptions occur. Also, decisions need to go up through two organizational structures that can have different cultures and different approval processes. The bottom line is that many months can be lost because of briefings and approvals through multiple organizations.

Second, considerable cost savings would result from elimination of the overlap and duplication. Although these figures should be updated, an analysis I conducted in 2006 conservatively estimated annual savings of between 48 and 125 person-years, or annual savings of approximately $4.8 million to $125 million. Equally important, both organizations suffer from staff shortages and they often hire from each other. These staff shortages hinder the speed with which procurements can be pursued. With amalgamation, not only would staff savings be found, but the staff shortages would also be eliminated.

Third, unless and until one minister is vested with overall accountability for defence procurement, it will be difficult if not impossible to introduce system-wide performance measures. Such measures are crucial in identifying bottlenecks and cost and quality issues and in focusing on appropriate actions for improvement. Measuring performance can also tell you what you’re doing well so you can share your successes with others.

The second impediment: there is a lack of performance measures. Two commonly used measures are the timeliness and the cost of acquisitions.

Speaking before a military trade show on May 29, 2013, Associate Defence Minister Kerry-Lynne Findlay acknowledged timeliness problems in defence procurement. “Going forward, we do need to do a better job of ensuring the procurement system benefits Canadian taxpayers,” she said. “We need to ensure the impact of their hard-earned dollars isn’t eroded by inflation due to excessive delays. We need to ensure our military capabilities remain robust and effective so we can continue to count on them when they are needed most.”

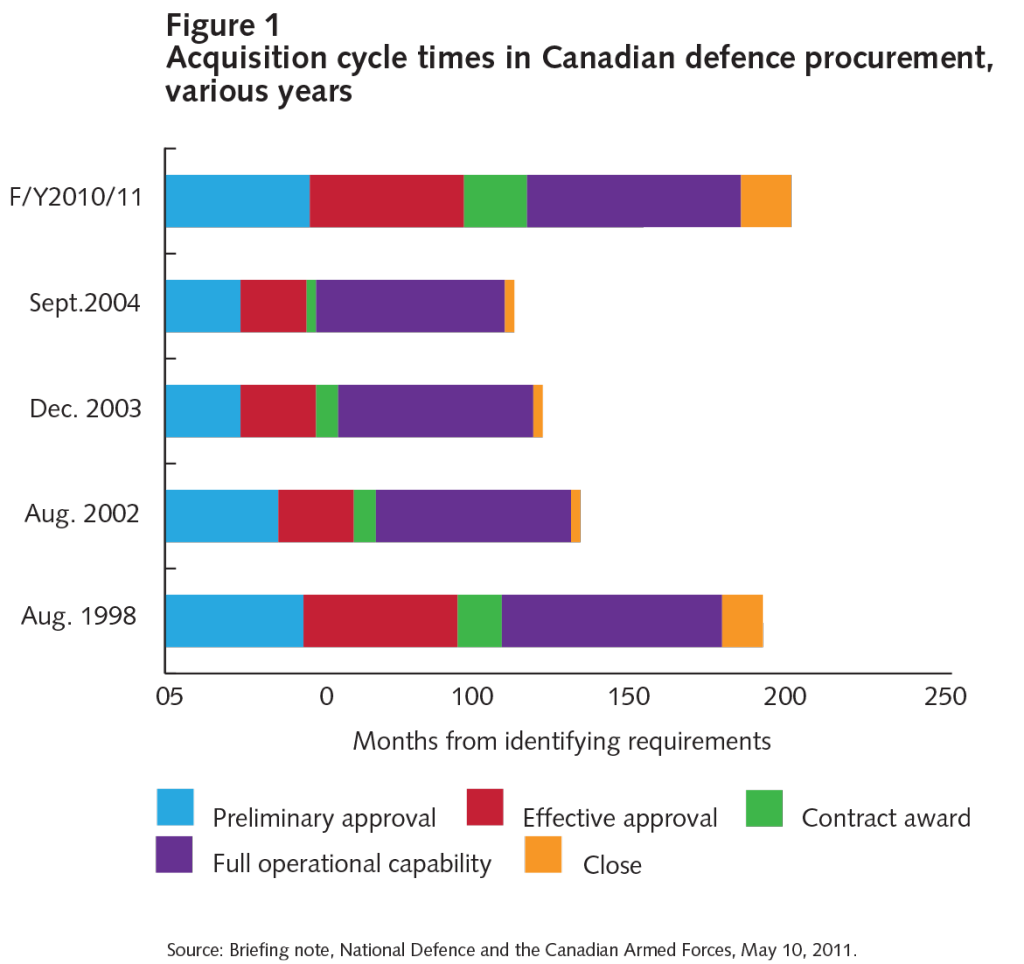

Minister Findlay went on to reveal that defence officials had recently completed a two-year study of past military purchases that was aimed at finding ways to speed up the process. She was quite right to insist upon shorter timelines. Notwithstanding the overlap and duplication between DND and PWGSC, significant reductions were achieved between 1998 and 2004. The overall procurement time was reduced from nearly 16 years to slightly over 9 years (figure 1).

Sadly, under her and her colleagues’ direction, these results were not sustained. By fiscal year 2010-11 all of the cycle-time gains achieved through 2004 had been eroded. The length of time to complete a project rose to over 16.5 years, an increase of 66 percent from 2004 to 2011. Today, it is taking longer to define our requirements and to complete an acquisition than it did in 1998. Figure 1 below shows these timelines.

Governments that have little to no understanding of defence procurement resort to sole-sourcing their purchases. Although there are instances when sole-sourcing is appropriate (such as an unforeseen emergency), these situations are relatively rare. Everyone understands that when you tell someone you are going to buy a product from him or her, you lose all bargaining power.

It is no different with defence procurement. Sole-sourcing is bad for industry, because there is no incentive for the seller to provide high-quality jobs, as there is when a purchase is undertaken through a competition. Sole-sourcing is bad for the taxpayer, because acquisitions can cost up to 20 percent more than they would through a competition, and it is the taxpayer who pays this extra cost.

Finally, sole-sourcing is a double disaster for the military. First, these extra costs come out of the limited DND capital budget, thereby eroding its purchasing power. Second — and this is perhaps the biggest drawback to sole-sourcing — without an open, fair and transparent competition, we can never be certain that we are providing the best product to our military.

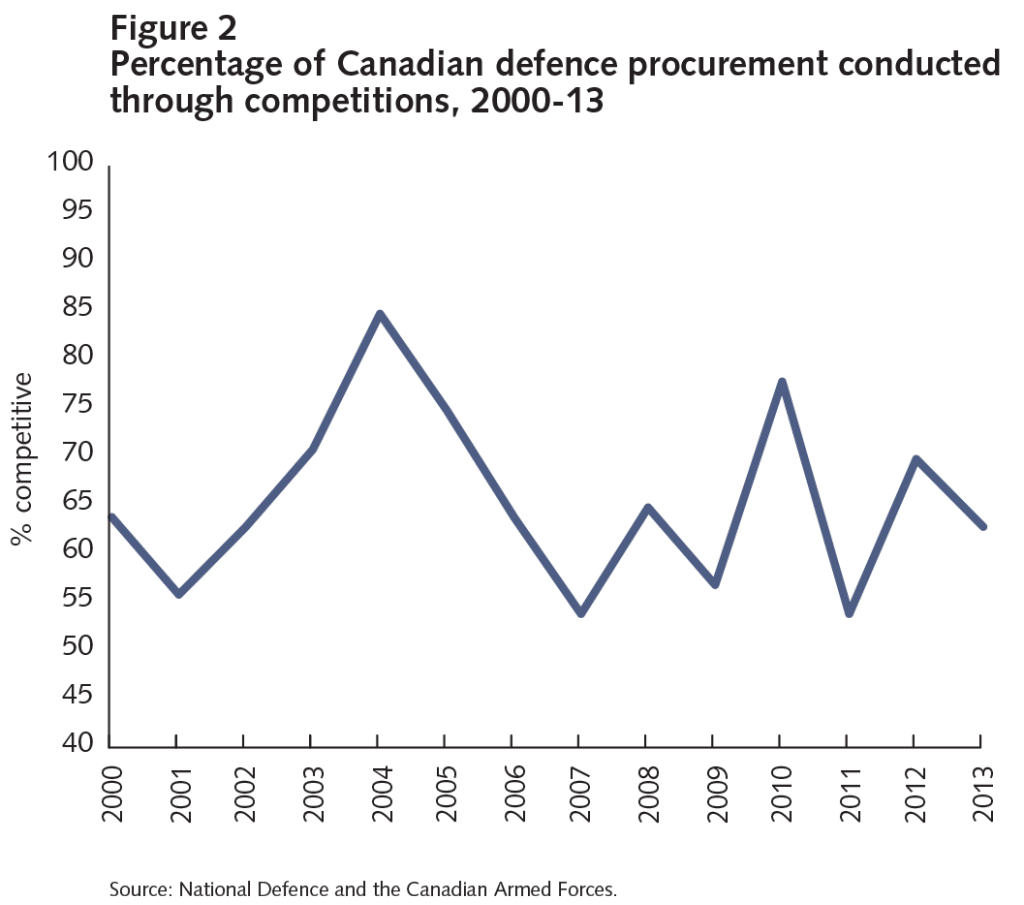

So what is the recent history with respect to sole-sourcing? Figure 2 shows the use of competitions for defence procurement between 2000 and 2013. From a high of 85 percent competitive procurement in 2004, the government has averaged only about 64 percent from 2005 through 2013. That means up to $5 billion was squandered.

Neither these nor any other system-wide indicators are currently made available, neither to the public nor to parliamentary committees. (The data presented here were obtained through an access-to-information request.)

Recommendation 2: The new defence procurement organization should provide system-wide performance measures on acquisition cycle times, identifying variances from plans based upon delays while waiting for external approvals, internal delays, contractor delays and changes in scope; on cost variances for all major projects; and on quality.

The third impediment to a well-run defence procurement organization is the lack of a cabinet-approved, long-term capital plan for defence spending. The benefits of such a plan would be far-reaching. From a purely communications-based standpoint, all Canadians would have a better understanding of how much money is being spent and how it is spent. Members of Parliament and the media could more readily question and challenge the government on how these capital initiatives would support the military’s role and mandate. Finally, industry would be a huge beneficiary of such a plan. Understanding future capital priorities would allow industry to form consortiums and position themselves in an optimal position to compete at the appropriate time.

Why has the government not prepared such a plan? The reason is simple. A public plan approved by the government would make it extremely difficult to randomly add or remove planned capital programs. If a strategic lift program were nowhere to be found in the plan, a government would have to publicly defend the decision to make it the number one priority. Similarly, a government would have to defend the removal of a Close Combat Vehicle program, a program that had been strongly defended and justified for many years.

On the other hand, preparation and promulgation of such a plan would be indicative of a government that has gone about the business of defence procurement in a properly structured manner. First, it has set the mandate and policy direction for the military. Second, it has approved the projects that support the mandate and role it has established for the military. Third, it has assured itself that there are sufficient funds available to undertake the projects in the plan. Preparation of such a plan would also be reflective of a government confident that, if need be, it can publicly justify changes to the plan.

Recommendation 3: Prepare and promulgate a cabinet-approved long-term capital plan for defence spending.

Implementing these recommendations would set defence procurement on the right path and provide the necessary benchmarks and feedback to ensure that it continues to improve. To do so would require an open, trusting and respectful bureaucratic-political relationship, a relationship that has sadly eroded over the past decade.

This article is part of the Equipping the Military special feature.