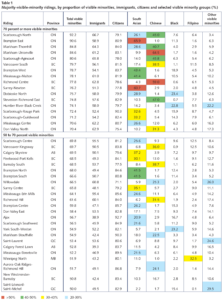

Data on immigration and ethnocultural diversity from the 2016 census show that many Canadian communities now have a larger percentage of visible minority residents than they did in 2011. Of the 338 federal ridings in Parliament, 41 have populations where visible minorities form the majority, compared with 33 five years earlier. (Data in this article and its figures and tables are from the 2016 Census Profile table “Canada, provinces, territories and federal electoral districts [2013 Representation Order],” unless noted otherwise.)

Figure 1 shows the growth in majority-visible-minority (MVM) ridings and the increase in ridings where visible minorities form a significant portion of the population (20 to 50 percent). Of these, 17 ridings have over 40 percent visible minorities. The mirror image of this trend is seen in the equally notable decrease in the number of ridings, mainly rural ones, where less than 5 percent of the population is visible minority.

Immigrants form the majority in most of the 41 MVM ridings; only two have less than 40 percent immigrants (see table 1). Citizenship rates are generally lower in these ridings, around 80 percent, than the national average of 90 percent, reflecting their greater proportion of recent immigrants who are not yet eligible for citizenship as well as a recently declining naturalization rate.

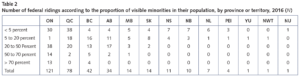

Figure 2 shows visible minority populations in federal ridings by province. Not surprisingly, Ontario and British Columbia have the largest numbers and shares of MVM ridings. Alberta has the biggest share of ridings that are 20 to 50 percent visible minority, reflecting its recent population growth. Of the largest provinces, Quebec has the most ridings with less than 5 percent visible minorities. Greater ethnic diversity in Manitoba compared with Saskatchewan is reflected at the riding level. Atlantic Canada and the North have the fewest ridings where visible minorities form a significant portion of the electorate. Table 2 provides the riding counts behind figure 2.

The 41 MVM ridings are campaign battlegrounds: British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, Southern Ontario’s 905 region and parts of Calgary, Montreal and Winnipeg.

In the 2015 election, all the main parties increased their numbers of visible minority candidates to attract these voters: according to my analysis, 14.4 percent of candidates were from visible minorities, a figure close to the percentage of visible minorities who are Canadian citizens. The election resulted in 47 visible minority MPs (13.9 percent of MPs), a record number and proportion for Canada. While most of these MPs were elected in ridings with large visible minority populations, 9 were from ridings with 20 percent or fewer visible minorities. When candidates are recruited for the 2019 election, more still are likely to be from visible minorities, given these demographic realities.

Table 1 lists the 41 MVM ridings with the percentage of visible minority residents, the percentage of immigrants and the overall rate of citizenship (among voting-age adults) in their populations. It shows the dominant communities, with red highlighting the communities that form a majority of the riding population. As one would expect, the diversity in these ridings reflects Canada’s overall immigration pattern: South Asians and Chinese are the largest groups of new arrivals, and they tend also to be concentrated geographically more than other groups.

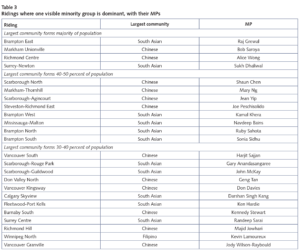

Canada’s relatively open approach to citizenship and political participation, compared with that of other countries, has ensured reasonable political representation of older and newer waves of new Canadians. However, the success of each group reflects to a considerable extent the degree to which its population is concentrated in certain ridings. Black Canadians are the third-largest visible minority group, but there is a striking contrast between their level of political representation and the parliamentary representation of South Asian (particularly Sikh) and Chinese communities.

Table 3 illustrates this. It shows the 24 ridings where one community forms 30 percent or more of the population. Over half (14) of these ridings are represented by an MP of the dominant group in that riding, another 3 have MPs from other visible minority groups, and 7 have MPs who are not from visible minorities. In many of the ridings, participants in nomination battles and the eventual candidates were all from the same visible minority group in the last election.

This pattern of representation, with the riding demographics behind it, makes it virtually impossible for any major political party to take explicit anti-immigration positions. Ridings with more than 40 percent visible minorities total 58, or 17 percent of all ridings, meaning that any path to a majority government requires winning these ridings. Although national issues play a greater part in political decisions by old and new Canadians alike, there is some evidence from recent campaigns of the limits of identity or wedge politics (as seen in the Conservative Party’s proposal for a “barbaric cultural practices” tip line, for example). Of the 33 ridings that had MVM populations in the 2015 election (according to 2011 data), the Liberals won 30.

Debates over immigration tend to be disputes over specific policies and issues rather than a wholesale questioning of their benefits. The muted response to the Liberal government’s recently released multi-year plan for increased immigration is one example: public debate has focused more on the need for greater support for integration programs and better controls on irregular asylum seekers than on the higher numbers themselves.

Does this mean that Canada is immune to the populist pressures in the United States and Europe? No country is an island. However, Canada’s first-past-the-post system combined with the high number of ridings with large immigrant and visible minority populations means that our political system is more immune than are the political systems of most other countries.

Photo: Shutterstock, by Niyazz.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.