For decades the world has been calling for some kind of miracle energy solution that would give us cheap, clean, widely available power. Nuclear power was part of that solution, but it couldn’t be transported, it didn’t prove to be as cheap as its visionaries had hoped, and environmentalists eventually came to oppose it with a passion equal to their loathing for fossil fuels.

Then we had the wild fantasy that was “cold fusion,” which was another kind of nuclear reaction — so the environmentalists probably would have hated it, too. Cold fusion was supposed to make nuclear technology even more widely available and economical, but that turned out to be wishful thinking. More than twenty years after the scientific community thoroughly debunked the infamous Fleischmann-Pons experiment, which claimed to have produced cold fusion, it remains little more than a pipe dream.

Green activists have been demanding a new energy source and pressed governments in the United States and Europe to invest massive subsidies into wind and solar power. But those, too, have proven to be costly fantasies. The energy they produce is prohibitively expensive. And unlike nuclear power, they are inefficient and unreliable. Solar works, of course, only when there’s sunshine, which rules out half the day and many months of the year in some regions. Wind works only when the wind blows, or doesn’t blow too much. Both technologies require duplication: a back-up generating system, to fire up when they’re not working. That just adds to the cost: instead of one power generator, you now need two. Some progress. Some solution.

But horizontal shale-gas fracking is progress. It is a solution. It’s cheap. It’s widely available. It’s clean. But it didn’t come out of some government-planned, spectacular moonshot-type mega-project. There isn’t much that’s sexy about it. It wasn’t created by famous geniuses, like Albert Einstein or Robert Oppenheimer. It was developed by a boring engineer making incremental, practical improvements on existing drilling technology, a private businessman almost no one has ever heard of, named George Mitchell…

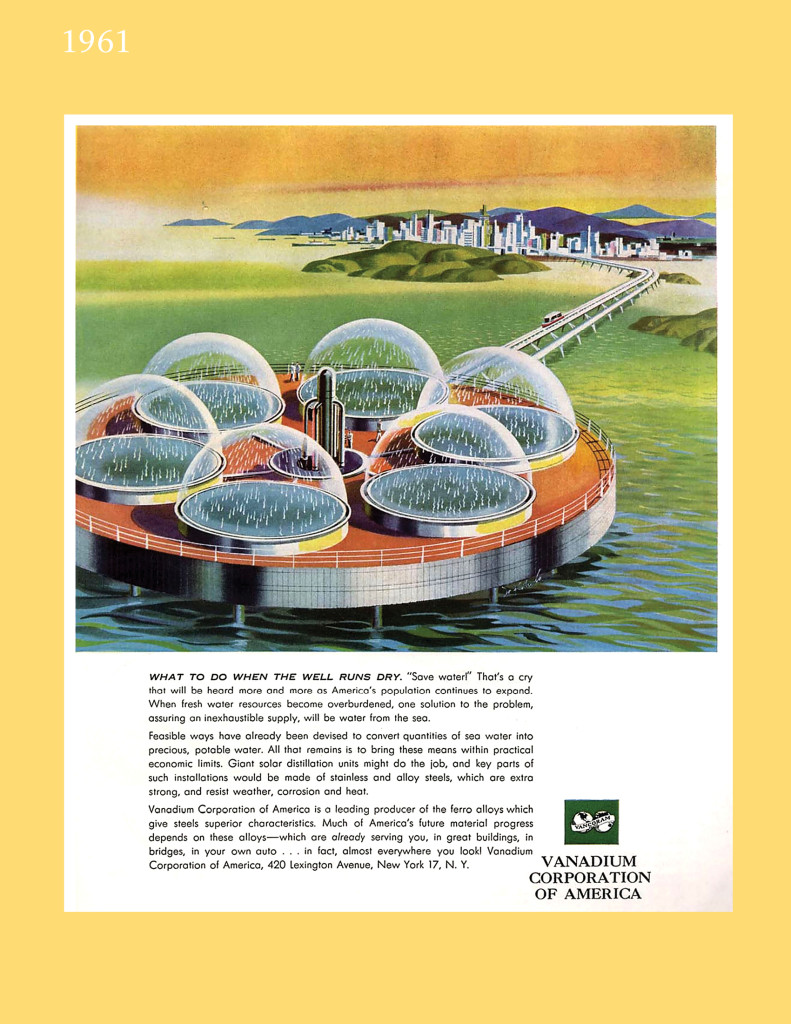

Fracking is the difference between daydreaming about “miracle” science-fiction solutions and an industry-based approach to realistic, achievable solutions. Science fiction is called fiction for a reason: it’s fun, but it’s make believe. Playwrights have a Latin term for that: “deus ex machina”— literally “god from the machine,” where God or an angel appears in the middle of a play (lowered onto the stage by a machine), to resolve an impossible problem with the plot. But life isn’t a Christmas movie or Greek play. There is no magical solution to our energy challenge.

Fracking resolves so many of the energy challenges we’ve faced until now, it’s difficult to overstate the implications.

Fracking isn’t some cheap plot gimmick. Natural gas isn’t some rarefied, enchanted mineral with fantastical properties, like the precious “unobtanium” they were seeking in James Cameron’s hit sci-fi film Avatar. It’s more like the smartphone: an incredible breakthrough in technology that has helped improve our lives, but one that came about only after decades of laying down the foundation with the necessary preceding technologies — computers, microchips, the Internet, wireless technologies, and a thousand other step-by-step developments.

Shale-gas fracking isn’t a deus ex machina, but the effect it is having comes awfully close to doing what that kind of plot contrivance does: it resolves so many of the energy challenges we’ve faced until now, it’s difficult to overstate the implications.

The most incredible effect of fracking is the impact it has on the amount of energy we have in the world. With one technological leap, we have increased the world’s gas reserves by 40 per cent, an astonishing magnitude. And it has opened up energy reserves in countries that have never had them before. Countries like Poland and Ukraine, which have had to depend on Russia, their hostile former occupier and autocratic petro-state, for their basic daily needs. Countries like Israel, surrounded by oil, all of it in the hands of enemies, but with virtually none of its own — a country that has lived the last six decades in a permanent state of existential insecurity, but also energy insecurity. The natural gas transformation is making energy-starved countries into energy powerhouses from scratch.

Before the shale-gas revolution arrived, fossil fuels were a bittersweet blessing: they helped our lives immensely, but they were largely controlled by the very regimes in the world that frequently made our lives worse. Russia, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Iran, Libya, Iraq — these are all places that have contributed to world instability (Russia and Iran still do), and the only reason they could have that kind of influence is that they were getting rich on their oil and gas racket.

Suddenly, though, it’s not just OPEC and “gas OPEC” that have this vital energy that we all want and need. Now, so many friendly, liberal, democratic countries have rich and accessible deposits of fossil fuels, too. Fracking doesn’t just change the balance of the world’s energy clout, it can change the balance of the world’s geopolitical power. It saps the strength of menacing regimes and empowers the good guys. It’s a historic shift and one that’s long overdue…

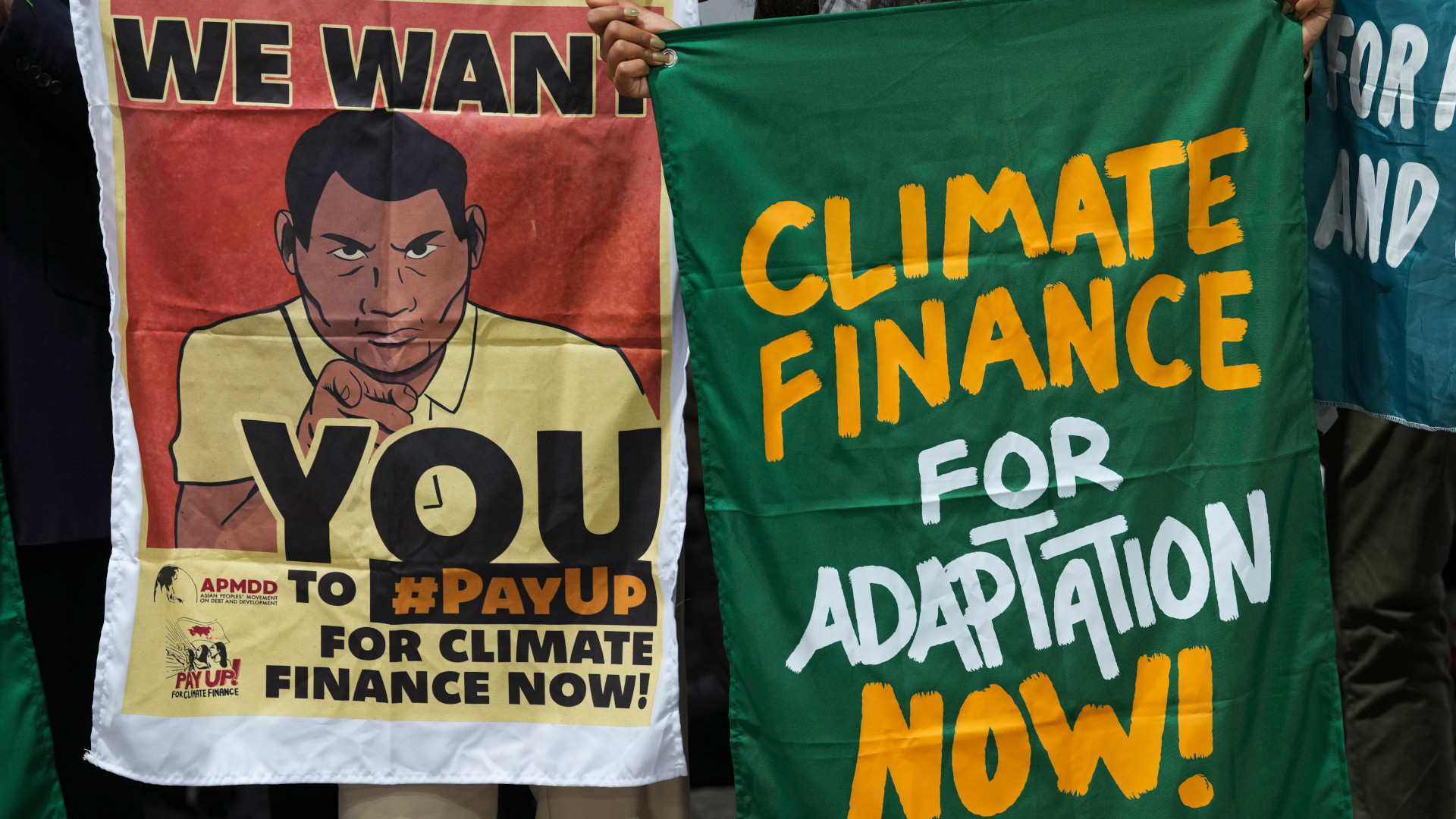

Certainly there are those who won’t let up on their campaign to battle fossil fuels, no matter how cheap or plentiful they may be, insisting that they are leading us toward climate change, or global warming. They’re largely the same people fighting against shale-gas fracking. They have a special hatred for fracking, because cheap, plentiful fossil fuels actually represent a step backwards for their agenda — a step further from their vision of a zero-carbon future. The shale-gas bonanza undermines one of their most persuasive arguments for carbon rationing: that we’re running out of fossil fuels.

But if your main priority truly is reducing carbon emissions, you should actually celebrate fracking. The existence of so much cheap gas, and the prospect of so many decades of it, has naturally prompted a rapid and substantial shift in the American energy economy away from other, less optimal fuel types and toward cleaner, lower-emission natural gas. Global-warming worriers can wring their hands about our fossil-fuel-based economies, urging us to spend billions more on solar and wind power. But economists have demonstrated that there is simply no way to feasibly replace all the power now generated by coal with wind turbines and solar farms.

By far the biggest advance in emissions reductions in the United States has been the spreading, countrywide re-orientation away from higher-emission power from coal and toward gas. A natural gas plant replacing a coal plant can produce the same amount of electricity but with emissions that are just a third of the level of that of the coal plant.

And that’s just the reduction in emissions of carbon dioxide — a harmless, colourless, odourless emission. Gas plants are even better when it comes to real pollutants: sulphur emissions, particulate pollution, and other actual environmental toxins that are real and immediate and affect our urban quality of life, rather than prospective and speculative, like the theory of man-made global warming.

But whatever you think about carbon emissions, the vast America-wide switchover to more efficient natural gas is doing what dozens of international “climate summits” and “renewable strategies” could not do: it’s reduced American CO2 emissions in 2012 to levels not seen since 1994. The U.S. Energy Information Administration traced the decline to one primary factor: cheap natural gas. It reported that in 2012 “lower natural gas prices resulted in reduced levels of coal generation, and increased natural gas generation — a less carbon-intensive fuel for power generation, which shifted power generation from the most carbon–intensive fossil fuel (coal) to the least carbon-intensive fossil fuel (natural gas).” While environmentalist activists were holding “vigils for climate justice,” politicians were giving away billions to unworkable alternative energy programs, and un bureaucrats and lobbyists jetted to lavish conferences to draft meaningless global charters, it was the private energy industry that was busy developing and deploying technologies that actually reduced carbon emissions at a remarkable rate.

For the extreme eco-purists — the people who want the world off all fossil fuels, everywhere — even that kind of sensational progress isn’t enough. The only grudging credit some of them will grant natural gas is to call it a “bridge fuel”: a lower-emission alternative to oil and coal that can be used temporarily until their green alchemists develop that far-fetched fantasy fuel of the future. That’s what the left-leaning Center for American Progress calls it: a “bridge fuel” to hold the U.S. economy over while we “conduct research on more efficient turbines, storage of renewable electricity, and other technologies that would generate nor low-carbon energy”…

Even President Barack Obama, who is hostile to fossil fuels, has been willing to accept natural gas is a “transition fuel.” It is more than that, of course. It’s a real alternative to coal, a real reducer of carbon emissions (for global warming worriers), a reducer of pollution, a real energy source that is affordable and plentiful. If the true believers in a zero-carbon economy want to call it a “bridge fuel” while they wait for the arrival of cold fusion or dilithium crystals, then let them call it that. Lucky for them, for us, for the world, we’ve got so much natural gas that we can build a very, very long bridge to keep us going while we await their messiah fuel.

Those people are idealists. And there is a place in this world for idealism. But the true test of character isn’t how moral they claim they would be in some hypothetical scenario. The true test of moral seriousness is how we make real decisions between imperfect choices.

Talking about what energy source might or might not be invented in forty years and then what might or might not be implemented and used, pretending that we can all get by with bicycles and windmills is childish — or at least unserious.

Ethics are about trade-offs. The trade-off for natural gas is western shale gas versus Russian Gazprom gas, Iranian ayatollah gas, or Qatari sharia gas. It’s the choice between ethical energy and conflict energy…

So which future will it be? The future promised by fracking’s advocates, where a shale-gas revolution will provide the world with cheap, plentiful, clean energy, freeing consumers — and even entire countries — from OPEC-style cartels? Or will it be the future promised by fracking’s opponents, where “unconventional” oil and gas is kept locked in the ground out of an abundance of caution, and energy is either bought dearly from Russia, Iran, and Qatar, or produced expensively, by highly subsidized wind turbines and solar panels? The answer is: both.

The fracking genie can’t be put back in the bottle in North America. Approximately 90 per cent of all oil and gas wells in the United States are fracked. The modern process was invented and perfected in the United States. It may sound newfangled or dangerous in media bubbles like New York and Los Angeles, but in U.S. states where oil and gas is produced, fracking can hardly even be called unconventional any more. Pockets of political resistance will likely continue — that’s the beauty of fifty U.S. states, each with their own laws — but nationally, it’s economically and politically entrenched, and one of the only things powering the United States out of its recession. Even those U.S. states that continue to resist fracking their own shale gas will still benefit from the cheaper gas piped in from other states. And unemployed young people will continue to cross state lines, making their homes in fracking boom towns. Four of the five fastest-growing cities in the United States are located in shale-gas bonanzas — two in Texas, and two in North Dakota.

It is the same thing in Canada: in the three western provinces, fracking is mainstream, and plans to export LNG to Asia got a staggering boost with the announcement of a $35-billion export facility in British Columbia — the largest single capital investment in Canadian history. As with the United States, anti-fracking resistance is greatest where familiarity with it is the lowest. But even if the anti-fracking riots in eastern provinces like New Brunswick are ultimately successful, and if the “temporary” moratoriums in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Quebec become permanent, those provinces will still benefit from using cheap shale gas from elsewhere in North America. And young workers in Atlantic Canada will still seek out high-paying jobs in the industry — they’ll just have to move to western Canada to do it.

Excerpted from Groundswell: The Case for Fracking (Toronto: McLelland & Stewart). © 2014 by Ezra Levant. Used by permission.

Photo: Shutterstock by FerrizFrames

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.