Effective reform is strengthened by knowledge of all the issues. The Canadian pension system can benefit from reform. The private sector offers research-substantiated options that, with the support of government, could address key concerns such as retirement income adequacy.

While it’s well known in the industry, some Canadians may be surprised to learn that defined benefit (DB) plans, other than those provided to public service employees, are declining and many remaining plans are no longer open to new members. At the same time, capital accumulation plans (CAPs) — which include defined contribution (DC) pension plans, deferred profit sharing plans (DPSPs), group registered retirement savings plans (GRRSPs) and group tax-free savings accounts (GTFSAs) — are growing in popularity.

Unfortunately some commentators have confused a decrease in DB pension plan membership with a decline in employer-sponsored retirement plans. While formal pension plan coverage in the private sector is commonly reported to have dropped to just over 24 percent over time, this statistic doesn’t mean employers and employees have given up on retirement plans; rather, the reported drop in pension coverage actually represents a move away from the burdens of pension legislation to more flexible solutions.

The Canadian pension system is not broken. Employers have maintained or created retirement programs by using CAPs (such as DPSPs and GRRSPs), which grew over 70 percent from 2000 to 2008, according to the Benefits Canada supplier directory, 2000-2008. Today, over 50 percent of Canadians have a retirement plan at work with CAPs providing over two-thirds of private sector workplace retirement plan coverage, as noted by Bob Baldwin in Canadian Public Policy in 2008).

However, the trend toward CAPs applies only to the private sector. Baldwin’s study found that only 1 percent of public sector workers are covered by a CAP compared with 50 percent of private sector workers.

By ignoring the presence of non-pension CAPs, any decline in workplace retirement coverage has been greatly exaggerated and risks missing the opportunity to leverage these successful products as a key part of any retirement reform.

Effective reform is strengthened by knowledge of all the issues. As the discussion on desired pension reform continues, it is concerning that some jurisdictions moved directly to solutions without considering the facts or issues that affect retirement savings plan coverage and adequacy.

To suggest, as some commentators have, that availability and cost are the main reasons more pension plans are not being created indicates a lack of understanding of the true barriers to plan creation.

Availability is not the issue. Feature-rich employer-sponsored plans are available to even the very smallest of companies. More employers do not offer retirement savings plans because they do not understand the benefits offering a plan holds for them and their company. More DC pension plans are not being created because the benefits they offer have been significantly eroded by the unnecessary application of multi-jurisdictional DB pension legislation to these plans.

Cost plays a role in the income adequacy equation but it’s not a negative one; rather, cost reflects the level of administrative and individual support required to effectively offer a particular plan type. In a CAP, most costs are incurred for supporting each plan member, while in a DB plan, support costs are largely at the plan level.

The adequacy of retirement income received from CAPs can be easily addressed through plan design considerations such as joining a plan early; making meaningful contributions; having a proper investment vehicle(s); and not making withdrawals prior to retirement. What makes a successful plan is described later in this article.

Retirement savings vehicles can be seen as a continuum, with DB plans at one end offering minimal member-level service, education, advice or customization. In a DB plan, there is virtually no member service requirement, because the employer makes key decisions such as how much to contribute and which investments to select. The employer uses specialized advisers for these decisions and members receive a basic annual statement.

To claim that the cost of CAPs is a major contributor to a shortfall in Canadian’s retirement income shows a lack of awareness of the competitiveness of CAP cost structure and the critical service features necessary to meet the needs of CAP sponsors and members.

At the other end of the spectrum are individual retirement and investment products, offering the greatest degree of personalized and customized investment selection and advice. A significant value proposition with individual products is the role of the personal adviser, who helps the client to design and implement a savings program and guides them over time to stick to the plan. This service is generally not available in a CAP.

CAPs are the middle ground, offering the member individualized investment choice, service, education, customized product features and some one-on-one advice. Any comparison of cost and value between DB plans with low service requirements and CAPs, which have high member-service needs, must recognize the significant differences between the two types of plans. This dramatic difference in service requirements between plan types further underscores the excellent value proposition offered by CAP service providers in Canada.

To claim that the cost of CAPs is a major contributor to a shortfall in Canadians’ retirement income shows a lack of awareness of the competitiveness of CAP cost structure and the critical service features necessary to meet the needs of CAP sponsors and members.

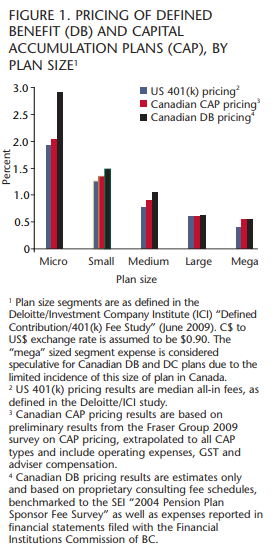

Recent benchmark studies on pricing (figure 1) demonstrate that CAPs offer a cost-effective alternative to DB plans as well as a flexible and feature-rich choice. CAP costs remain very competitive with the costs of DB plans despite requiring significantly more member support. Canadian CAP costs are also competitive with US CAP costs, even though US plans have economies of scale resulting from a market 23 times larger than Canada’s.

Understanding the costs of a CAP requires an appreciation of the value of the services that plan members receive. CAPs require individual members to make important decisions based on the information provided to them. The group retirement plan industry has developed a wide range of tools and resources to help members, all within a competitive cost structure.

The complexity of decisions increases as participants near retirement age. For example, members in the 20-to-40 age range want to know if they should enrol in the plan, how much to contribute, how to allocate assets to investment choices, and if portfolio rebalancing is required. To help answer these questions, the group retirement plan industry uses toll-free call centres, Web sites, printed resources and group information sessions.

For the 40-to-50 age range, all of the same resources are available, but the questions change. At this stage, participants want to know if they should increase their contributions to achieve their saving goals, if they are overweighted in equities, and whether they should change their investor risk profile as they get nearer to retirement. System-generated messages and personal data-driven retirement income probability illustrations on statements are additional resources available to these members.

In the over-50 age group, plan members are asking about catch-up contributions to stay on track. They also want to know if they should think about annuities and, ultimately, what to do with the funds they’ve accumulated. All of the tools and resources mentioned above are available to them, and there may be an opportunity to do more to meet the needs of these members.

Three solutions have been proposed most frequently during the pension reform debate: government-sponsored DC plans (by province or attached to CPP); expanding and/or enhancing the CPP; and creating a “super fund.” Each of these options, which may seem attractive at first glance, raises serious concerns among industry experts.

Some commentators are suggesting a significant increase in CPP benefit levels as a possible solution. Aside from the additional mandatory payroll tax to employers, the anticipated benefit provided by the CPP simply won’t be attractive to future members of the plan (if they are under age 45) given that they could potentially achieve a much higher retirement income through private plans.

To illustrate (table 1), if a new member of the CPP, age 25, were to take the current required employer and member CPP contribution and direct it to a private plan earning 4 percent a year, that member would achieve a significantly higher retirement income — in some cases as much as double, depending on the amount of time invested. These calculations yield similar results even for people joining the plan in their mid-40s.

One suggestion for pension reform is the introduction of a government-sponsored DC plan. It’s unclear, however, what the true benefits would be, given that reasonably priced programs are already broadly available to even the smallest of employers.

If this solution is adopted, there is significant potential for confusion between the nature of a non-guaranteed government-sponsored DC plan and the existing guaranteed government pension programs such as the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Old Age Security (OAS). Participants in a government-sponsored DC plan wouldn’t be entitled to receive a guaranteed pension amount when they retire. However, there is a danger that participants may erroneously think that because of government involvement, there is some form of implicit or explicit government support that would mitigate investment losses and pension shortfalls if they arise.

In addition, governments would be challenged to develop the in-depth administrative support needed to educate, inform and report to plan members. This expertise has been developed in the private sector over the past 20 years. The CPP and OAS have no existing infrastructure for these important tasks.

Furthermore, it would be expensive for government to offer DC plans and be competitive because almost all administrative costs of operating these plans are driven at the member level. For some initial time period, a new government plan would have limited assets over which to spread these costs. The private sector already has sizable asset levels offering economies of scale to offset much of the fixed costs of serving members.

The administration costs of government plans should not be subsidized directly or indirectly by general government revenues, nor is it appropriate to expect private industry to subsidize government sponsored plan costs by providing systems and expertise at artificially discounted rates.

A growing number of commentators are calling for a large, pan-Canadian “super fund” approach with the goals of facilitating labour mobility, protecting retirement savings, and benefiting from economies of scale. This approach doesn’t give consideration to individual investment risk. As Jack Mintz has pointed out, a super fund member who is close to retirement and whose benefit falls 18 percent (average 12-month drop in large pension fund market values in 2008) may not be consoled by the fact he or she was in an “inexpensive” fund.

Also, a super fund isn’t immune to investment issues such as asset writeoffs and significantly negative rates of return, nor is it guaranteed that a super fund would be run efficiently.

DB plans have always been impractical for small and medium-sized employers where a small change in plan demographics can significantly affect funding requirements. More recently, even large employers have moved away from DB plans, which lost 193,000 members from 1991 to 2006, according to Statistics Canada (“Shifting Plans,” 2009).

Two government-related causes have greatly influenced the disappearance of DB plans: complexity and the cost of unplanned features.

Complexity: The various provincial and federal regulators of pension plans across Canada have been unable to harmonize the regulations and rules for DB plans. DB plan sponsors operating in more than one province have to expend significant resources to ensure proper compliance with the current patchwork of regulation that exists in Canada.

This situation has created a compliance burden from a risk and resourcing perspective, adding costs that plan sponsors have become more and more unwilling to pay. When added to existing accounting complications and ownership-of-surplus issues, DB plans are increasingly unattractive to plan sponsors.

Cost of unplanned features: In addition, provinces have imposed significant costs on plan sponsors by requiring pension plans to incur additional liabilities that the plans were never designed for. These expenses make DB plans cost-prohibitive and place Canadian DB plan sponsors at a competitive disadvantage compared with firms in other countries, including the US and the UK.

A further pressure on DB plans is the increasing awareness of the significant dichotomy that exists between private and public sector retirement plans. Almost 100 percent of public sector workers are covered by a DB plan and the average cost for these DB plans has been estimated to represent 33 percent of pay, according to a 2007 C.D. Howe study entitled “Ill-Defined Benefits.”

It seems unlikely that as taxpayers become more aware of the cost of these public pensions they will be willing to continue to fund them. As the disappearance of DB coverage continues, it is critical that governments leverage CAPs to help private sector workers, and potentially themselves, save for retirement. The relative merits of DBs vs. CAPs can be argued, but the reality for many employers is that a CAP solution is the only choice they have. For an increasing number of employers, CAPs have become the design of choice. By recognizing the value of CAPs, government can help create an environment that improves their effectiveness.

The success of a CAP depends on a number of critical factors, which combine to help determine whether a plan member will have adequate retirement income. These success factors include

- Joining early

- Making meaningful contributions G Making an appropriate investment choice

- Understanding the impact of withdrawals

- Recognizing age-adjusted investment risk

A worker must join a CAP early enough to ensure tax-free compounding works effectively for him or her. In the industry, joining a plan is called enrolment.

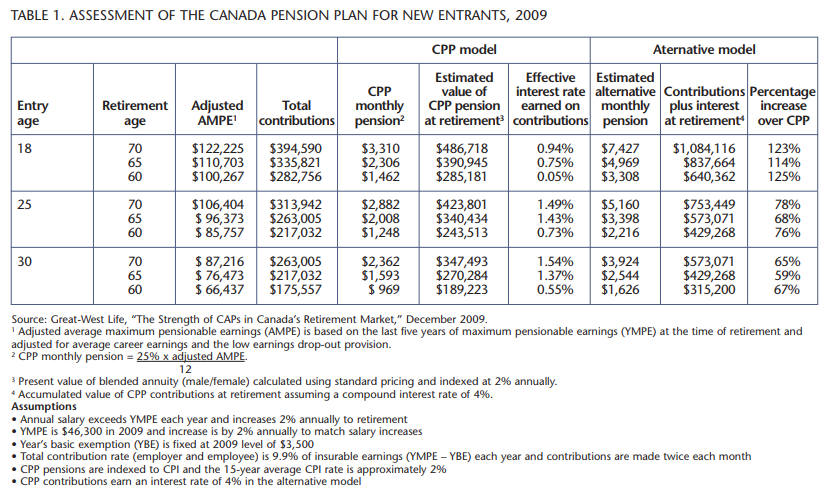

The following chart (figure 2) illustrates the impact of postponing enrolment on plan savings in the long term. A member who contributes $2,000 a year and earns 6 percent annually would have an extra $300,000 in savings by joining at age 20 instead of age 35.

Too many plan designs make participation optional. To ensure employees take advantage of this tax-free compounding, mandatory participation (automatic enrolment) is necessary. A 2008 study showed only 61 percent of DC pension plans and 16 percent of GRRSPs have mandatory participation, according to the 2008 Benefits Canada CAP Benchmark Report.

Modifying existing pension and RRSP rules to recognize CAPs and make them more attractive to employers and better address retirement income adequacy for plan members would represent a practical and effective solution to Canada’s retirement savings challenges.

To provide adequate retirement income members must combine sufficient contributions over time with investment growth. Although members have tools to calculate how much they should contribute, few take the time to use them. In the 2008 CAP Member Survey by Benefits Canada, only 35 percent of members said they used the decision-making tools provided by their plans. This lack of member engagement is the key reason design options such as automatic enrolment and automatic contribution escalation need to be offered.

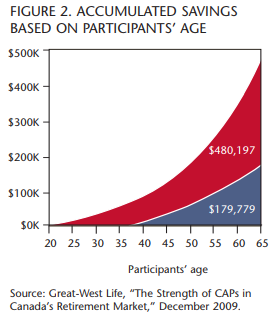

Employers can do their part by offering a meaningful “matching” contribution to the plan. When matching is available, it’s critical that member contributions be sufficient to maximize the employer contribution. Establishing automatic escalation of member contributions can help build the contribution amounts to an optimal level. Figure 3 highlights the impact of higher contribution rates on retirement income.

A plan member must choose an appropriate investment option that will maximize growth while recognizing his or her risk tolerance. While excellent investment options may be available in the member’s plan, rules may allow the member to select other funds that may not suit his or her risk tolerance.

Members who don’t choose an investment option may be placed in a default option. Often these default options assume that the member will only be in the default fund for the short term. However, too many members aren’t engaged — they don’t make a subsequent investment decision, so these short-term holdings become long-term investments. Statistics on Canadian plan members investing in default funds are hard to find, but US numbers show over 65 percent of members are invested in default funds, according to James J. Choi and colleagues in their 2001 paper “For Better or For Worse: Default Effects and 401(k) Savings Behavior.” Having approved default options that can work for the long-term, offer a multi-manager approach and automatically address diversification, risk/ return optimization, individual investment risk profile and regular rebalancing would address this issue.

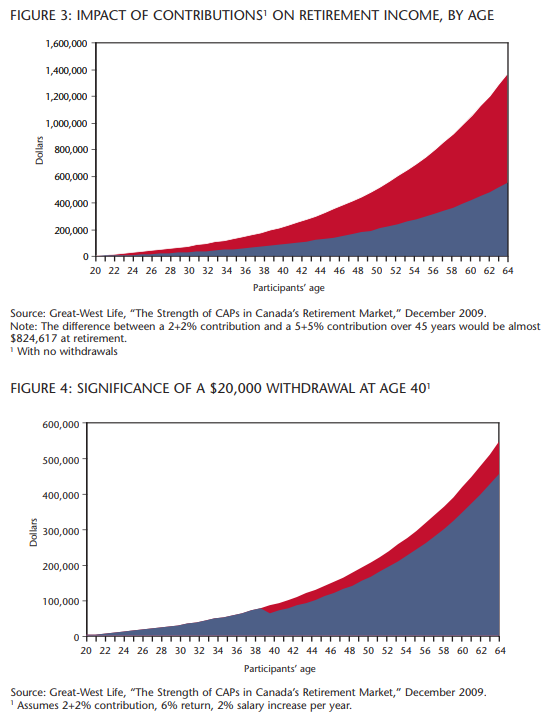

The member must also leave the money invested in the plan so it can grow. Too many plans allow in-service withdrawals and the impact is staggering. Between 1992 and 2001, 66 percent of tax filers aged 20 to 59 contributed to an RRSP, but over 25 percent made at least one withdrawal. While all ages are equally likely to make a withdrawal, alarmingly, older members make larger and more frequent withdrawals and are less likely to pay them back. Figure 4 illustrates the serious consequences for retirement fund growth of one $20,000 withdrawal at age 40, which would cost the member almost $91,000 by retirement age. While it may be a controversial point, if the plan goal is to provide adequate retirement income, withdrawals should not be allowed.

As a member approaches retirement, efforts should be made to avoid dramatic market fluctuations. Older plan members are looking to purchase an income that won’t be outlived or be affected significantly by market shifts or inflation. There are options available today but this is an area where there is room for imaginative future product development.

Feature-rich, cost-effective defined contribution pension plans are already available to even the smallest of companies. So why don’t more sponsors offer these plans, especially when the perceived value by members is significantly higher than the actual cost?

Small and medium-size employers may not realize what’s available because they’re focused on running their business. Advice from a benefits adviser often helps convince the employer that a retirement plan can work for their business, for their employees and for themselves as members.

A pension plan must be “sold” because employers are daunted by the complexity and restrictive nature of pension requirements, which were developed for DB plans but inappropriately applied to DC plans. It takes a great deal of knowledge and persistence to help an employer understand that a DC plan may be the best way to help employees prepare adequately for retirement at an appropriate age.

To an employer, the extra cost and complexity of establishing a pension plan may not be worth the benefits — they will simply opt to offer a GRRSP. In this process the value of intermediation by an adviser is something that needs to be recognized. Modifying existing pension and RRSP rules to recognize CAPs and make them more attractive to employers and better address retirement income adequacy for plan members would represent a practical and effective solution to Canada’s retirement savings challenges.

Changes to be made to create a national employer-sponsored product (with one set of rules) should include

Member:

- Automatic enrolment: Plan members maximize the benefits of tax-deferred compounding and any employer contributions

- Automatic escalation of contributions: Savings increase as members draw closer to retirement

- Approved default options: Members who don’t choose an investment are more likely to have their contributions invested appropriately

- Locking in: Members can’t make withdrawals that will significantly reduce their retirement savings in the long run

Sponsor:

- Longer vesting periods: Employers can encourage staff retention

- Flexible contribution rates: Employers can adjust their contributions if circumstances change (with adequate notice to members)

- Sponsor held harmless if complying with CAP guidelines: Encourages new plan creation

- No payroll taxes on employer contribution: Tax treatment of employer contributions to non-pension CAPs should receive same tax treatment as pension plan contributions to encourage plan creation and employer contributions In the US, 401(k) plans have provided a framework for employer-sponsored retirement plans that can generate sufficient retirement income for employees, while providing safeguards and guidelines for employers. A similar approach is possible in this country, with a uniquely Canadian flavour. The solution would be to recognize GRRSPs as a formal plan type (just the mention of pension plan will deter many employers) allowing the features described above and providing one set of national rules.

This new GRRSP plan type could be launched with an organized awareness campaign to educate employers and encourage plan creation. Giving provincial pension regulatory bodies a mandate to promote the creation of plans (along with modifying pension legislation to allow the above features and not apply DB-related requirements) could also help raise employer awareness.

Many of us in the group retirement industry believe that the imagination and creativity shown by the industry in developing CAPs over the years can, with regulatory support, build Canadian products that would successfully help Canadians reach their retirement goals. We’re optimistic that the current attention on pension reform could move these required changes ahead.

The evolution of the DC solution in Canada has come a long way. Regulators (through the Joint Forum of Financial Market Regulators) have acknowledged the unique nature of CAPs and implemented universally adopted standards (the Capital Accumulation Plan Guidelines) covering best practices for sponsors, members, advisers and service providers. This accomplishment stands as a strong example of what can be achieved when industry and government work together toward a clear goal.

Within today’s outdated regulatory framework, plan sponsors have worked diligently to engage their plan members and arrange for the support necessary to achieve the best retirement income possible for their employees. Service providers, through open competition, have evolved their product and service features to a level that is world class.

Despite these efforts, the retirement savings system in Canada would benefit from improvement, with a particular emphasis on leveraging CAPs and encouraging more employers to consider them as an appropriate option for their employees.

It’s encouraging that federal and provincial governments have agreed to a thorough review of the issues, goals and available approaches, including the contribution that could be made by CAPs. Arriving at national solutions could represent a huge step forward to help working Canadians achieve a more secure retirement. This critical issue will affect the well-being of working Canadians and deserves the best efforts of all stakeholders to seek effective solutions.

Photo: Shutterstock