Things have changed a lot since the founding of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. Once a symbol of an inevitable march toward global free markets, today it more often serves as a reminder of how quixotic that process has become. Fatigue is spilling over to the bilateral and regional level, where there has been a flurry of negotiations, but few meaningful outcomes. Who would fault busy executives for turning their attention to other things?

Many would like to blame the current state of affairs on out-of-touch bureaucrats and short-sighted politicians. Yet the business community has responsibilities too. Companies and their representatives need to define new priorities and communicate effectively the gains that free trade brings to consumers, workers and innovators. They need to build relationships across borders and bridge diverging national interests.

So what can business do to set right the ship of trade? What strategies will bring forth the next wave of liberalization?

It starts by better understanding how shifts in the global balance of power have made it harder for countries to cooperate on trade. In this new reality, national business groups should strengthen ties with their foreign counterparts and apply pressure at multiple points in an increasingly fragmented regime. Diplomacy can no longer be left to the diplomats.

The evolution of the trading system since the early 1990s has been complex. There has been enormous growth in cross-border trade and investment, as companies have expanded into new markets and previously closed-off economies have joined global production networks. In contrast, the treaties and institutions that underpin these trade flows have remained remarkably static.

When the North American Free Trade Agreement and the WTO hit the world stage in the mid-1990s, free trade seemed like an unstoppable force. Tariffs fell to unprecedented levels (at least among developed countries). New rules on nontariff barriers and services aimed to halt protectionism by other means and liberalize new corners of the economy.

There were big gaps, however. For instance, trade in agriculture went almost untouched, there was no agreement on foreign investment, and hopes that countries would expand their commitments to liberalize trade in services went unrealized. In practice, many hard-fought intellectual property protections have been worth little more than the paper on which they are written. All the while, fundamental changes in the way companies do business — driven by global supply chains and the spread of the digital economy — have highlighted gaps like these and revealed the importance of addressing them.

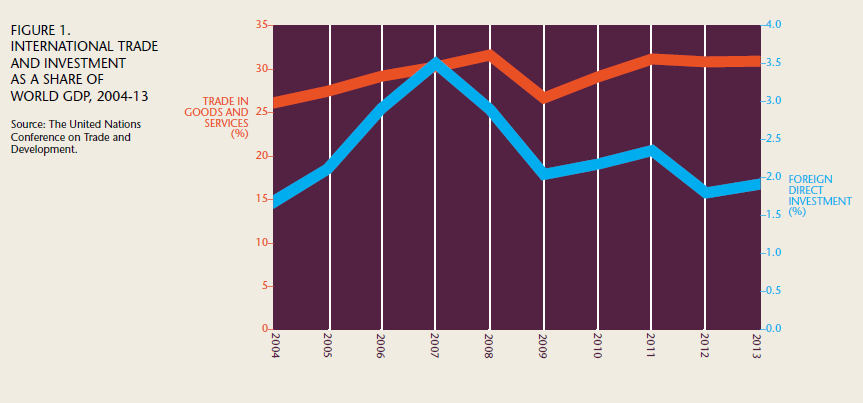

More recently, the aftermath of the 2008-09 financial crisis shows that government officials can sidestep trade rules by using regulatory changes, customs procedures, state aid and other creative measures to favour domestic industries. Six years into a painfully slow recovery, trade as a share of world GDP is barely at its pre-crisis level, and foreign investment has fared much worse (see figure 1).

Attempts to plug the gaps in the trade regime have mostly failed. From the collapse of the Multilateral Investment Agreement and Free Trade Area of the Americas, to the never-ending Doha Round, business has been served with a series of disappointments.

There are a few bright spots, of course. Some countries have taken steps to liberalize on their own, as Canada did by eliminating tariffs on capital goods in the manufacturing sector. The WTO surprised many in late 2013 when members endorsed a package of measures at the Bali Ministerial, including a treaty on trade facilitation that could cut global trade costs by up to 10 percent. Sector talks in Geneva on services and environmental goods are off to a good start. And despite the rise of beggar-thy-neighbour policies during the recession, they pale in comparison to the harsh protectionism of the 1930s.

Another positive sign is that the Western trading powers have started to negotiating agreements among themselves. Canada and the EU concluded one last year. The US and Japan are facing off in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and the EU is conducting separate bilateral talks with both of them. These negotiations could be game-changers, especially if the three can agree to recognize each other’s regulatory requirements and product standards, upon which most of the world relies. However, the success of these initiatives is far from assured, and similarly ambitious agreements with the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries are a long way away.

In many ways, trade liberalization has been a victim of its own success. Access to rich-world consumers gave emerging economies markets to sell their wares. Leading multinationals set up shop, bringing with them much-needed capital and technology. Local firms learned from them and upgraded their abilities. Economic growth accelerated, pulling hundreds of millions out of poverty in the process. This is how globalization was supposed to work.

But the rise of new trade centres — combined with the fallout from the financial crisis, which disproportionately hit rich countries — has had a profound effect on the distribution of economic clout. The BRICs now account for more than a quarter of global output. Add Mexico, Turkey, Indonesia and South Korea and South Africa, and combined they come close to the total output of the G7 economies.

This new configuration is a challenge for international cooperation. The days when the US, the EU, Japan and Canada (known as the Quad) could sit down and agree on what to do, and the rest of the world would fall into line, are over. New access to these markets does not mean what it used to. Their tariffs are already low by world standards, and growing south-south trade means there are other options. The economic significance of China, for example, makes it easier for Russia to weather Western sanctions.

Another problem is that the BRICs et al. have been cautious to embrace markets. Willing to take advantage of export opportunities, they are less interested in undertaking domestic reforms that would put foreign companies on an even footing. The state continues to play a central role in the economy. For instance, more than half of the top companies in China and India are owned by the government. Underdeveloped social programs mean price controls and subsidies are often the easiest way to meet the needs of vulnerable citizens. In this context, building consensus on trade rules that go beyond traditional tariff cuts is not easy.

It is not just the emerging markets that are making it hard to find common ground. Advanced economies may understand each other when it comes to the balance of state and market, but today’s “next generation” trade issues are harder for them to handle. Tariffs are quite obviously intended to protect domestic industry. Regulatory discrepancies are motivated, at least in principle, by the pursuit of legitimate public policy objectives. Removing these barriers requires the involvement of numerous government agencies and is more likely to provoke opposition from civil society.

For freer trade, business should not abandon the multilateral system.

Thankfully, the tensions we see today have so far only slowed down liberalization. A wholesale reversal, as the world experienced during the interwar period (another time of great economic and geopolitical change) seems unlikely. Nonetheless, free traders need to stay vigilant.

What lessons should the business community draw for the future? First, there is no big-bang solution for freer global trade. Business should not give up on the multilateral system, but it cannot afford to put all its eggs in the WTO basket. Regional trade agreements are here to stay. There is also much that can be done outside traditional trade negotiations, in forums like the G20 and in national capitals around the world. Business needs to work incrementally at all levels. Second, inclusiveness matters. The rise of new trade powers means that OECD industry groups have to forge partnerships with their counterparts in these markets, and work with them to build a common vision. Finally, trade will not be addressed in isolation. Business has to ensure that policies affecting trade — in the areas of energy, climate change, product safety and privacy, for instance — are effective and better coordinated.

Having the private sector play a more prominent role in global governance is not a new idea. During the interwar period a group of industrialists, financiers and traders formed the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), calling themselves “merchants of peace.”

Once again, business needs to lead. In 2013, over a dozen national industry associations from all five continents formed the B20 Coalition, with the Canadian Chamber of Commerce as founding chair. The goal of the group is to build a more cohesive business community and to bring continuity to the global economic agenda. One of the coalition’s first steps was to develop the following recommendations for the G20 leaders at the 2014 Summit in Brisbane:

- Reaffirm the standstill pledge on protectionism that started during the crisis and strengthen the capacity of the WTO to monitor compliance and establish a timeline to roll back protectionist measures;

- Comprehensively implement the Trade Facilitation Agreement without delay;

- Develop a new, balanced agenda to complete the Doha Round that includes agriculture and nonagriculture market access, as well as services;

- Take unilateral steps to improve customs procedures and to reduce barriers to imports and the supply of services;

- Make progress on plurilateral agreements in the areas of services, environmental goods and information technology, with the ultimate aim of multilateralizing them under the WTO;

- Explore ways to bring disciplines of government procurement, foreign direct investment, export restrictions and state-owned enterprises into the WTO; and

- Increase the coherence of new bilateral and regional trade agreements with the WTO system by monitoring them and studying their effects, and encouraging more liberal rules of origin in those negotiations.

The recommendations were informed by the need to simultaneously push for liberalization at all levels, and to do so in a mutually reinforcing way. The coalition and its member associations, which span developed and developing economies, disseminated them widely and have been monitoring their implementation by national governments, working in tandem with the ICC and other international industry groups.

Thanks in part to efforts like these, there are real signs of progress since Brisbane. Within weeks of the summit, the WTO adopted the Trade Facilitation Agreement — the first multilateral trade treaty in over 20 years. Countries are working tirelessly in Geneva to “recalibrate” the Doha agenda in hopes of concluding a modest deal this year that would clean the slate for future talks. There are signs of life at the regional level too. After nearly two years of treading water, the contours of the Trans-Pacific Partnership are emerging, and American officials are musing about how China might be included down the road.

Restoring positive momentum to the global trading system is an uphill battle and everyone needs to roll up their sleeves. For Canada especially — a middle economy highly exposed to cracks in the trading system — indifference is not an option. Industry groups around the world can and should guide governments towards a more open world economy, where companies compete and innovate on a level playing field. The alternative destination is in no one’s interest, especially not Canada’s.

Photo: Shutterstock