Eight years after Johannes Lampe’s 28-year-old son Hana took his own life, recounting that loss remains a raw and painful experience.

Lampe, who is president of Nunatsiavut, a self-governing Inuit region in Newfoundland and Labrador, is desperate to get Canadians to understand how suicide is stripping his communities of their vital young men. He needs to share the extent of the problem here in Kuujjuaq, an isolated community in northern Quebec. So, as Inuit leaders gathered to launch the National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy, Lampe told his son’s story, that of his 17-year-old nephew, John-John, and of his brother, Maku.

All three young men are the victims of this public health crisis, which is claiming Inuit lives in Labrador at a staggeringly high rate: 25 times the national average.

“It is something that causes a lot of hurt, a lot of pain and a lot of suffering,” Lampe told those gathered to launch the strategy, which the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), the national political organization, developed. “It affects a whole community too – in fact, a whole nation.”

Lampe couldn’t eat or sleep after Hana died. He withdrew from his family. It wasn’t until his elderly mother told him how much she, too, was suffering at the loss of her grandson, that Lampe could finally reach out and begin to seek and receive the comfort he needed to go on, he explained, with tears rolling down his cheeks.

Many of those suffering probably think they are alone, Lampe says. “But we are not alone. We are a whole nation, and we can work together.”

ITK released its suicide prevention strategy last week, 60 years after Inuit in Canada’s high Arctic were forced from their traditional lands and relocated against their will. The suicide prevention strategy points to that relocation as a driving factor behind the suicides among the first generation of youth to grow up in settlements. The strategy is designed to begin to counter that historical trauma and generations of colonization and abuse.

“We have done all we can in the pages of our strategy to create a unified, globally informed, Inuit-specific approach to suicide prevention in Inuit Nunangat,” says ITK President Natan Obed.

“The National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy is premised on the belief that suicide among Inuit is a preventable public health crisis that demands a systematic response from all who wish to work with Inuit,” he said.

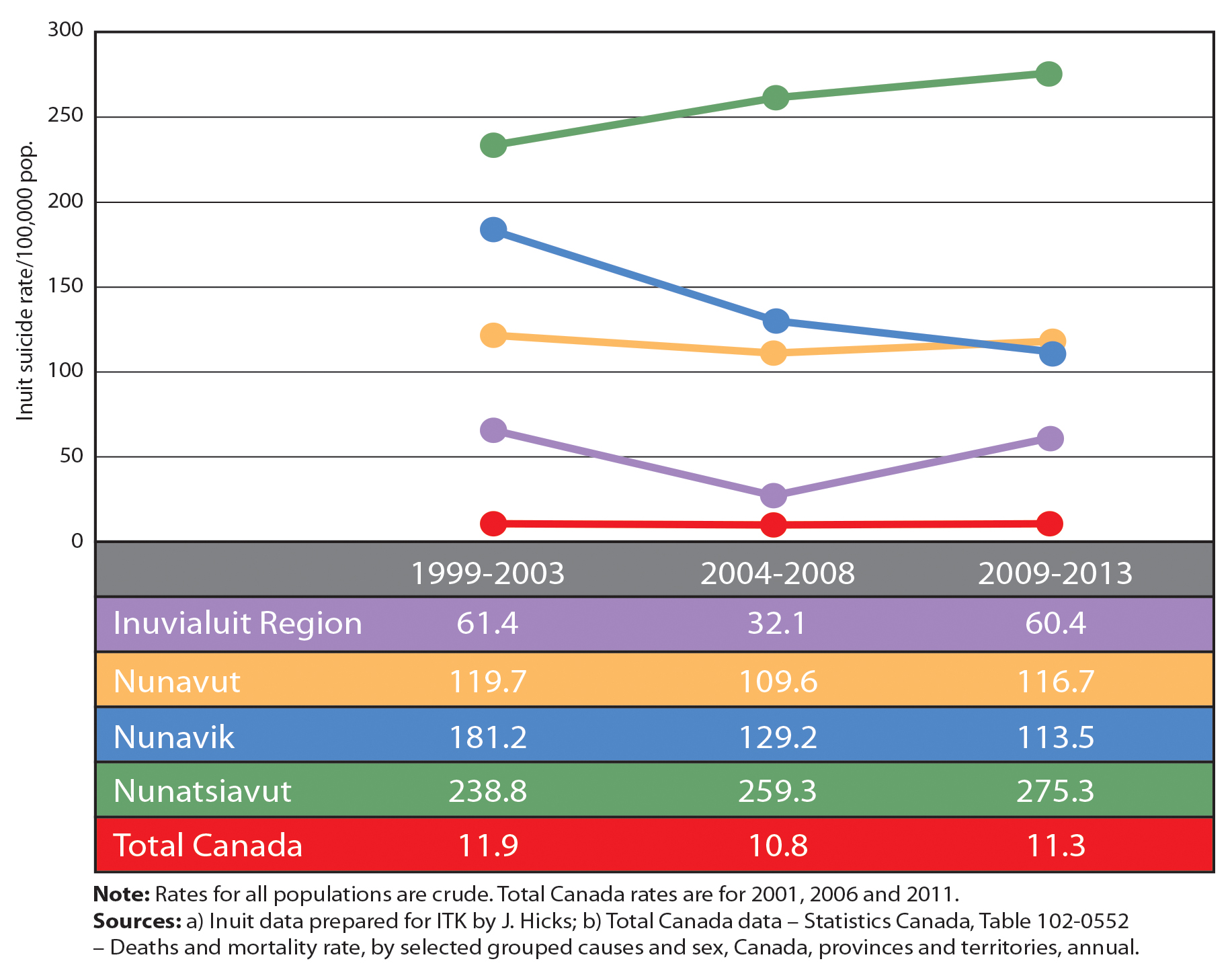

The strategy is a response to the disproportionately high suicide rates across Inuit Nunangat, the four regions that make up the Inuit homeland in Canada: Nunavik, Nunavut, Inuvialuit in the Northwest Territories, and Nunatsiavut, where Lampe lives.

In Nunavik, as in Nunavut, the suicide rate among Inuit is 10 times greater than it is in the rest of Canada.

Between 1999 and 2013, 745 Inuit died by suicide, according to statistics that researcher Jack Hicks compiled for ITK directly from coroner’s files. From 2013 to April of 2016, an additional 73 people took their own lives in Nunavut alone, according to figures from Nunavut’s chief coroner. There have also been clusters of deaths since then in both Nunavik and Nunatsiavut, bringing the death toll to more than 800 lives lost. Most of them were young people under 30.

It was in Nunatsiavut that Obed (who is from Nain, Labrador) had hoped to draw national attention to the severity of the suicide crisis. His initial plan was to launch the strategy in Hebron, an abandoned community in Nunatsiavut from which, in 1956, Inuit families — including his own family — were relocated to settlements in southern Labrador, but heavy fog forced him to abandon this plan.

The strategy emphasizes the need to recognize the roots of what make Inuit so susceptible to risk. These root cause include the historical and intergenerational trauma caused by relocation, sexual and physical abuse that began in residential schools and continues today, the slaughter of dog teams, and years-long absences for tuberculosis treatment. All of these historical events separated families and destroyed traditional Inuit ways of life.

“These are all things that created the social environment of the 1970s that led to the first time of our Inuit communities having elevated rates of suicide,” says Obed.

The strategy also focuses on the need to redress the social inequities that set Inuit apart from other Canadians: life expectancy 10 years lower; income levels more than four times lower; high school completion rates almost three times lower; and food insecurity more than 8.5 times higher.

Kuujjuaq, where the announcement was ultimately held, has been devastated in the past eight months by 5 suicides and 85 suicide attempts among young people, says Kuujjuaq mayor Tunu Napartuk.

But the scale of the crisis is most evident in Nunatsiavut, where the suicide rate between 2009 and 2013 was 275 deaths per 100,000. That compares with the national suicide rate of 11 per 100,000 in 2013.

For Sean Lyall, Minister of Culture, Recreation and Tourism in Nunatsiavut, the launch of the prevention strategy provides hope after the decades of loss. His best friend in Nain, Labrador, committed suicide more than 20 years ago, when they were both 18. In January 2016, Dorothy Angnatok, a young Inuit outreach coordinator for a cultural program that helps high-risk youth, also took her own life — a devastating event for Nunatsiavut youth.

“Everyone has been touched (by suicide),” Lyall says. He believes the new strategy will help draw the Inuit regions together to work collectively on the crisis.

Unlike many reactive policy approaches to try to address the high rates of suicide among some of Canada’s Indigenous communities, and particularly among young Indigenous people, this strategy takes a broad scope, long-term view of the actions and resources required to lower the suicide risk.

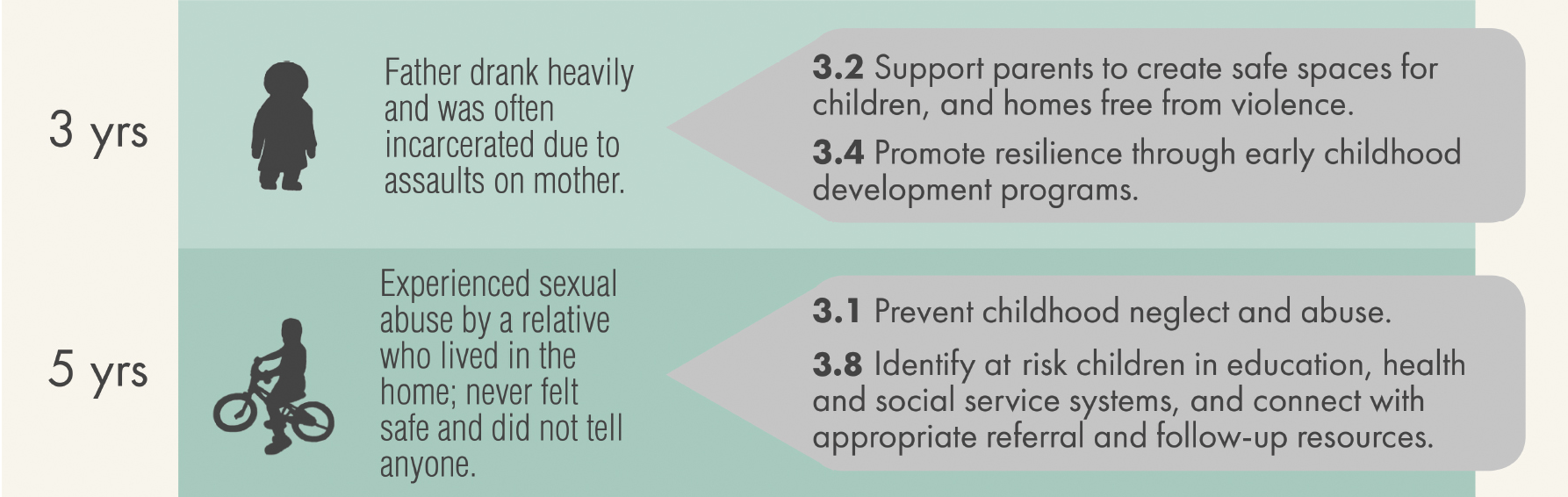

The strategy document includes a stark graphic (p. 29) that lays out the devastating problems that children face at different stages of their lives and how the strategy proposes to intervene to reduce the risk:

It outlines the need to instill protective factors at every phase of a child’s development, such as providing parenting resources, early childhood education development, identifying at-risk children and connecting people with culturally appropriate mental health resources, and improving social equity.

“Most strategies acknowledge the existence of risk factors that start early in life, but they focus all of their attention on the imminent risks or the acute risk such as access to means. It’s too late at that point,” says Allison Crawford, a psychiatrist and medical director of the Northern Psychiatric Outreach Program and Telepsychiatry at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, at the University of Toronto. Crawford helped ITK draft its strategy.

“The difference in this strategy is that we are taking a preventative approach, drawing from the evidence that many people who end their lives by suicide have histories of childhood adversity, including childhood sexual abuse. That sets them on a pathway or a course of cumulative risk,” Crawford says.

This preventative approach is a unique aspect of this strategy, and one that could inspire policy-makers across Canada (which still lacks a national suicide prevention strategy) but also internationally, says Brian Mishara, director of the Centre for Research and Intervention on Suicide and Euthanasia at the Université du Québec à Montréal.

“This is an important reorientation of the priorities,” says Mishara, who had an opportunity to review and comment on the strategy before its public release.

Other well-intended strategies or government policy approaches designed to address suicide have failed, because they invest in intervening only after the situation has deteriorated so much that there are mounting suicidal behaviours in a community, says Mishara.

“It’s a lot easier to look at [suicidal risk] as something that starts from birth and childhood. They are taking a real-mental-health-promotion approach rather than a fix-the-problem approach. I think it’s a good document,” he says.

The challenge ITK now faces, as Mishara points out, will be to leverage resources from the federal and provincial/territorial governments to take coordinated, evidence-based action based on the ITK strategy. Effective suicide prevention in these regions will also have to involve coordinating with Quebec’s successful suicide prevention plan, and with the strategies the other Inuit regions such as Nunavut are developing. ITK’s next step will be to develop a costed implementation strategy, with target dates and assigned responsibilities – something Obed acknowledges is crucial.

At the strategy’s launch, Health Minister Jane Philpott committed $9 million over three years to support ITK in carrying out the strategy.

“The statistics, try as they may to tell the story, aren’t what tell the story most powerfully,” said Philpott, tearing up as she spoke at the launch. “Every statistic…is a human being — that is, a son, a daughter, or a brother or a sister. The personal stories that I’ve heard are the ones that drive us here today.”

Obed, for whom the creation and launch of this strategy has been a deeply personal journey, hopes the rest of Canada will work with Inuit to try to stem this tide.

“I think of all the things that have gone on in the families of those who were relocated,” he said.

“If we truly value Inuit life, then we will take the actions necessary to address the root causes of suicide.”

Photo: Kuujjuaq, Quebec — Natan Obed, president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, releases the National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy (July 27, 2016)

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.