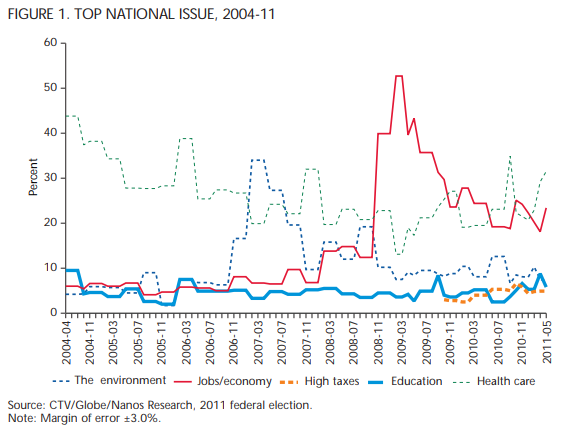

In 1993, Kim Campbell famously said that elections are no time to talk seriously about policy. This was certainly true for environment, climate change and energy issues in the recent federal election. Green issues did not warrant a single question in either the French or English leaders’ debate or form a part of the political conversation among the leaders. Nor did these issues break through the horse-race mentality of pollsters and the media. Perhaps this is not surprising: following a peak in 2006, the environment now ranks low among priorities for Canadians (figure 1).

Contrast this with 2008, when the Liberal Party and the Green Party treated these issues as central organizing principles of their platforms (and lost). In that election, Elizabeth May campaigned nationally for the Green Party and participated in the leaders’ debates, garnering more than 930,000 votes. This time around, she took a calculated risk in focusing on winning a single historic seat for the Greens. That strategy was successful, but her party slipped dramatically in its share of the national popular vote.

Was this election a setback for green issues? Does it mean that Canadians are no longer interested in protecting the environment or that governments should treat it as a low priority? Not really, but now that we have a federal Conservative majority government and four years to consider the options, there are a few lessons to be learned.

First, in the last few elections, green issues have been too easily reduced to the old polarities of the environment versus the economy. In 2008, that meant equating Stéphane Dion’s revenue-neutral Green Shift with higher taxes, and assuming that green policies automatically come with higher energy costs for consumers. In 2011, the Conservative Party suggested that the NDP’s cap-and-trade proposal would immediately add 10 cents a litre to the price of gas at the pump, stoking consumer fears that the policy would weaken economic recovery.

So, political lesson number one from the 2011 federal campaign is that the economy trumps the environment. The majority of the population continue to believe at some level that action on the environment will hurt their pocketbooks.

Capitalizing on a largely uninformed electorate, the recent political debates, including those in minority Parliaments over more than five years, have been largely ideological, stalling progress not only on climate change but on a wide range of environmental issues.

This might be a blinding flash of the obvious, but in other spheres — away from political expediency — civil society, many businesses, investors, subnational governments, municipalities and our trading partners have recognized that the environment and the economy do not stand in opposition to one another. In fact, these diverse interests view green policies as being core to economic development and growth. US President Barack Obama has described this agenda as “winning the future,” and Ontario Conservative Leader Tim Hudak has staked part of his electoral success on the following premise: “Energy policy needs to be viewed as economic policy, not environmental policy.”

Moving the debate from the environment versus the economy to the environment as a critical component of the economy will require a fundamental reorientation of the way we view these issues. In much the same way that Canada had to completely rethink how we presented economic and trade measures to the US following 9/11, so we need to recast the environment from being a nebulous “should” to an economic “must.” Decreasing our ecological footprints, for ourselves and future generations, remains a worthy objective in its own right, but the lesson of the 2011 election is that green issues must be framed in viable economic terms to gain political traction.

There is a cohort of Canadians coming of age who do not believe that action on the environment hurts the economy and see economic opportunity in green solutions. They have been trained in Canada and around the world in disciplines like business, engineering, architecture, materials design, nanotechnology and information technology to find creative solutions to environmental challenges.

The second and broader lesson is that advocating strongly for green policies comes with a high political cost. Stéphane Dion paid the price in 2008. Former Australian Prime

Minister Kevin Rudd campaigned aggressively on climate change policies and was replaced. Yes, there were other issues for both leaders, but their green platforms cost them politically. Premier Dalton McGuinty in Ontario is under fire for going too far with his Green Energy Act and the Feed-in Tariff Program. The US midterm elections offered a number of examples of Democrats losing votes over their positions on cap-and-trade legislation. Former British Columbia Premier Gordon Campbell may be an exception, since he introduced a carbon tax and was then elected with a majority, but political blood was spilled there as well.

If, as Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Lester Thurow suggested, “the proper role of government in capitalist societies is to represent the interests of the future to the present,” then we must find a way to depoliticize and reduce the political risk of environmental action.

Doing so requires that politicians bring more than a handful of stakeholders onside with new initiatives. Canadian citizens wear many hats — taxpayer, ratepayer, consumer and voter. Premier McGuinty’s recent introduction and then retraction of eco-fees is a perfect example of forgetting how these other dimensions can surface at the ballot box. Politicians who want to advance solutions need to keep in mind the complexity of the electorate.

Third, there is also the unintended consequence of the green protest vote. While it is, by its very nature, a vote against the status quo, it can have the opposite effect on government, often delivering a “stay the course” result and reinforcing the political risks for a government of action. In order to change this dynamic, environmental policies need to move into the political mainstream and beyond parking a vote with the Green Party. Those who care about these issues must work between campaigns and within political parties to make sure that differences between party platforms create an informed debate about political solutions as opposed to easy political divisions that reinforce historic rather than modern paradigms.

The final lesson is that there are important demographic forces at play in the larger discussion about environmental policy. The 2011 election was decided by baby boomers, by highlighting more traditional perspectives and framing issues that are important as they retire and age. Boomers are preoccupied with health care, pensions, low taxes and ensuring that the economy is strong enough to protect them if they falter.

This will still be true when the next election rolls around in October 2015. But there is a demographic tension here and a potential clash of world views. We are in the second decade of the 21st century, and the next generation is looking at a far different set of future economic and planetary challenges than those of the 1970s.

Generation Y is looking for governments and business to address environmental, infrastructure and fiscal deficits; to make better use of finite natural resources; and to find efficiencies that will help match the carrying capacity of the planet.

There is a cohort of Canadians coming who do not believe that action on the environment hurts the economy and see economic opportunity in green solutions. They have been trained in Canada and around the world in disciplines like business, engineering, architecture, materials design, nanotechnology and information technology to find creative solutions to environmental challenges. There is a generation of pragmatists coming who are looking for integrated solutions to complex challenges, not either/or choices.

Their influence is discounted because they don’t vote in large numbers today. While we saw a wave of activism in initiatives such as Apathy Is Boring, LeadNow, vote mobs, engagement through social media and Rick Mercer’s call to action, it did not, in the end, make a significant difference at the polls. Voter turnout was up by only 3 percent across the country, and this was not exclusively the youth vote. Unless the millennials mark their Xs in significant numbers in 2015, they will have limited impact on getting the next government to focus on their priorities. Can they really afford to wait until 2019 for change?

These lessons apply beyond the political realm. In order to move forward on environmental challenges, we need more efficiencies not only in industrial processes and energy consumption, but also in politics and public policy.

While Canada continues to address issues such as greenhouse gas emissions, water quality and air quality as separate, distinct issues, other countries have developed integrated responses when it comes to green issues, linking them to productivity, natural resource efficiencies and economic prosperity in a low-consumption economy. This means Canada is in line with the US on regulations but out of sync with the rest of the world on greening economic policy

Moreover, countries that we are competing with and in — the US, China, South Korea, Mexico, Brazil — as well as the European Union have aligned their internal and foreign policies, so that their economic and environment policies are linked to strategies on R&D, innovation, trade and global competitiveness.

The federal government (politicians and the public service) needs to catch up and recognize that development of low-consumption systems is no longer dependent on government policy. It’s slowly becoming embedded in business models and a part of companies’ differentiation strategies. It is part of what consumers are seeking. It has a momentum of its own. That said, the pace and scope of benefits could be significantly increased with a coherent and long-term policy approach from the federal government. It’s time for Canada to develop multi-year and multi-sector strategies that transcend partisan politics. These are intergenerational issues and cannot continue to be political footballs.

The low profile of environmental issues in the polls need not be seen as a setback for the environment, nor should it permit us to endlessly defer these issues for the next four years. Rather, it should be viewed as an opportunity to bring our current aspirations for economic growth in line with opportunities for clean energy and production, natural resource productivity, R&D expansion and a burgeoning domestic and export sector in clean technology. It provides an opportunity to build on Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s campaign announcement to support developing the shift to clean electricity supply in the Atlantic region into a modern energy strategy for the country, one that would also address carbon emissions.

The United Kingdom offers a useful example. For the past 10 years it has had a 2050 energy strategy and climate change response, allowing government, business, investors and civil society to collaborate on the difficult work of shifting their energy systems. Importantly, it has also served to depoliticize the issues and allow Labour and Conservative governments to proceed in the same direction while tweaking policies at the margins.

For the last seven years in Canada, Liberal and Conservative federal governments have either radically changed what was previously proposed or annually revised — but never formalized — the rules that would regulate emissions. This leaves provincial governments to design approaches independent of federal policy. And it leaves businesses to either guess where policy is headed or simply defer decisions about capital investments. The confusion has an economic cost.

Canada needs more than regulation to address these challenges. It needs a more sophisticated set of applied policies that integrate environmental outcomes and economic benefit. And that means we have to have the difficult conversation about whether and where economic instruments could be introduced to address climate change and to realize results in improving our air, our water and our ecology. This would require serious study and economic analysis by the best minds in the country. But it could be done.

The worst-kept secret in Canada is that the business community is looking for a market solution on climate change, with many favouring a carbon tax or a transparent, economy-wide price on carbon. This has been political poison after the last two elections, but it is a viable policy option nonetheless. However, it requires openly discussing politically sensitive issues like the impact of carbon policy on energy prices; regional and territorial revenue distribution; Equalization; and provincial jurisdiction over energy. Tackling these files was impossible in a minority government, but perhaps a majority government will be able to start fresh.

Preston Manning has long pressed the Conservative Party to be bolder on the environment by “making the harnessing of market mechanisms to the task of environmental protection and conservation the ‘signature contribution’ of conservatives to environmental and economic sustainability.”

We have four years to bring our political discourse in line with pragmatic environmental thinking that would green and grow our economy. We must take note of the lessons of the past few elections and try something different. If we take the political bite out of progressive policies, in an innovative country like ours we can create wealth and opportunities, while still protecting the beauty and resilience of our natural ecosystem.

Photo: Shutterstock