Federalism’s strength is its diversity. Like elections attracting, repelling and charging each other, Canada’s premiers are the source of much of our political energy. While our premiers occasionally united against the federal government, and sometimes form regional blocs with differing interpretations of the public good, the good governance of Canada depends on them.

Peter Lougheed, who governed Alberta from 1971 to 1985, is the premier over the last 40 years who has emitted the largest spark. To commemorate the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP), a jury of prominent public policy practitioners evaluated the men and women who have led our provinces since the creation of the IRPP. Peter Lougheed was the overwhelming choice as the best premier. As L. Ian MacDonald, editor of Policy Options, described in his interview with Lougheed published in this edition, “It was like watching Secretariat win the Belmont by 31 lengths.” Lougheed was the top pick of 21 of the 30 members of the jury and was in the top 5 of every juror. Of the nine leadership attributes that the Policy Options survey tested, Lougheed won all nine.

Four others joined Peter Lougheed in the pantheon of best premiers: William Davis, Allan Blakeney, Frank McKenna and Robert Bourassa (only Danny Williams of more contemporary premiers was in the running with the top 5). These five leaders are not of one piece and exhibit the diverse leadership traits we expect in a federal system: think of the charisma of Lougheed, the geniality of Davis, the intellectual gifts of Blakeney, the entrepreneurial drive of McKenna and the patience of Bourassa.

Four of the five started their premierships at roughly the same time (Bourassa in 1970, Davis, Lougheed and Blakeney all in 1971) and thus faced the same broad challenges over the course of their partnerships. Blakeney in his memoirs recalls his first federal-provincial conference in the fall of 1971, which began with a dinner at 24 Sussex. At that dinner, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Premier Bourassa got into a heated discussion over the Constitution (the Victoria Charter had been rejected by Quebec in July 1971) while the other premiers, shocked, looked on. Then at a later federal-provincial meeting, Blakeney witnessed a similar vituperative exchange between Trudeau and Premier René Lévesque, initially in French. Blakeney recalls: “Then they looked around the table and noticed the French was too fast for the rest of us, we were not getting the full benefit of their remarks, so they switched to English and continued the pleasantries. By this time, we had become a little more familiar with the Quebec style of political address.”

Blakeney’s ironic recollection of Quebec “pleasantries” makes the point that each of the top 5 premiers was challenged by the seminal political reality of their generation — the rise of Québécois nationalism — and how best to deal with it within the framework of Canadian federalism. Frank McKenna, winning office in 1987, missed the Trudeau initiative of repatriating the Constitution — which so consumed the energies of Lougheed, Davis, Blakeney and Bourassa — but he was equally preoccupied with how best to reconcile Quebec to the constitutional settlement of 1982. McKenna was a key participant in the Meech Lake and Charlottetown debates of 1987-92, along with Robert Bourassa, the great survivor, who was still active when all of his fellow premiers from 1971 (when he first met Blakeney) had by then retired.

These five leaders are not of one piece and exhibit the diverse leadership traits we expect in a federal system: think of the charisma of Lougheed, the geniality of Davis, the intellectual gifts of Blakeney, the entrepreneurial drive of McKenna, and

the patience of Bourassa.

But if Quebec and the Constitution was the defining federal-provincial issue for all five of our “best premiers” right behind was the phenomena of the New West and the rebalancing of Confederation through the impact of energy. In 1973, OPEC tripled the price of oil from US$3 a barrel to $9 a barrel — oil revenues leapt from $500 million to $1.5 billion. In 1979, the price of oil tripled again. Economic power surged west. Peter Lougheed articulated the values of the New West well before the jump in the price of oil, but joined by Blakeney, Lougheed led the fight to ensure that the western provinces retained the right to manage their own resources and reap the benefits. Bill Davis, for his part, had to cope with how higher energy prices were transforming the economy of Canada, and with it the traditional heartland of Ontario. The enduring challenge of how to create a workable framework to accommodate Quebec within a wider union while dealing with the rise of the New West were the two overarching national challenges faced by each of our top 5.

Each of these leaders responded to the challenges differently, and their skills and approaches make a leadership whole greater than the sum of their parts. Each of the top 5 is examined in more detail below (and in separate articles in this magazine) but first let us examine the criteria by which they were judged.

Richard E. Neustadt, adviser to every Democratic president from Harry Truman to Bill Clinton and author of Presidential Power, the most influential book on the theory and practice of presidential leadership (“Presidential power is the power to persuade”), assessed presidents on four criteria. Evaluating an American president and a Canadian premier is not an exactly comparable process — Neustadt emphasizes foreign policy and the president’s stance under pressure in our nuclear age.

But three elements of the Neustadt criteria were adopted and adapted by Policy Options to fit the Canadian context. The first was political winability and the ability to persuade. There is a role for prophets and John F. Kennedy, in Profiles in Courage, wrote about leaders who were willing to lose over principle. But Neustadt rightly emphasizes that great leaders win elections, keep winning them and leave a record that allows their party to at least survive if not thrive (the truly great masters like Sir John A. Macdonald or Franklin Roosevelt realign the electorate).

What were the leaders’ purposes, asks Neustadt, “and did they run with or against the grain of history”? Canada’s premiers deal with the problems that most affect the daily lives of our citizens — health, education, infrastructure, clean water and social assistance. Premiers were therefore evaluated on their vision for their province, fiscal management and social infrastructure like hospital and higher education. A premier’s contribution to the national debate, both defending his province’s interest while thinking of Canada as a whole, is also a critical part of a premier’s “purposes.”

Lastly, Neustadt discusses the “feel” of a leader — his understanding of the nature of the power in the reality of his time and how this understanding of himself and others contributes to his legacy or the impact left on his province and country, its character and public standing. Superior leadership of any type is to be admired. But not all legacies are the same.

Three of our best premiers chosen by the jury — Davis, Blakeney and Bourassa — were “transactional,” to use the description by James MacGregor Burns in his book Leadership. Such leaders are skilled at understanding their electorates and making the exchanges and compromises necessary to keep the political system working and their parties in power. More rarely, there are also “transformational” leaders, who change the value system of their followers and by so doing change definitions of the public interest. Frank McKenna was transformational in New Brunswick; Peter Lougheed was transformational in Alberta and in Canada as a whole.

So dominant has been the Conservative Party provincially in Alberta since the Lougheed era that it is difficult to recall how miniscule Lougheed’s political base was when he became leader of the Alberta Progressive Conservative Party in 1965.

Each of the other premiers selected by the Policy Options panel inherited either a ruling dynasty or a party that had recently governed. Not Peter Lougheed — he started virtually from scratch. The Conservatives had never formed a government in Alberta and had no seats in the legislature; surveys gave them support in the low teens.

But Lougheed saw that Alberta was changing: the rurally dominated “back to the bible” era of Ernest Manning (when we lived in Edmonton, our family used to listen to Manning, who still had a religious radio show even as premier) was giving way to the urban concerns of Calgary and Edmonton. In the 1967 election, Lougheed won six seats (five of them in Edmonton and Calgary) and 26 percent of the popular vote. Ernest Manning was still a dominant figure but Lougheed had established the Progressive Conservatives as the party of the new emerging urban middle class. With Manning retired, in the 1971 election under the slogan “NOW,” Lougheed won 49 seats to the Social Credit Party’s 25 seats. In the 1975, 1979 and 1982 elections, he led the Progressive Conservative Party to landslide victories. In 1982, for example, he won 75 seats out of 79. This record is simply one of the most impressive in Canadian party history.

Lougheed himself personified the new Alberta he so strongly represented. His grandfather was a federal cabinet minister, but like most westerners, his family fortune declined during the Depression. Education was the way to move up and Lougheed enrolled at the University of Alberta, where he combined his academic pursuits with playing football for the Edmonton Eskimos and becoming president of the student union. In 1954, he went to Harvard to earn an MBA and returned to Calgary to practise law and work in business.

Upon becoming premier in 1971, Lougheed began by re-organizing government from the unstructured, informal style of the Socreds into a rational model based on current business practices. A cabinet committee system was created, the executive council machinery became the organizing centre and over time the Alberta public service was nearly doubled. An Alberta version of the “Quiet Revolution” ensued.

The hodgepodge of past royalty regimes were replaced by a uniform 12.5 percent, which greatly increased revenues. These enhanced revenues in turn were spent on investments in education, health and medical research. Lougheed’s goal was to use resource revenue to create an enduring provincial economy based on learning and technology. In 1976, he created the Heritage Fund (now worth $15 billion) to put aside current reserves for future use. Also, as part of his pan-Canadian approach, Lougheed encouraged the other provinces to borrow from the fund for their capital needs.

Lougheed’s vision was that a stronger West would make for a better Canada. The West “will be a strong part of Canada a decade from now” (quoted in David Kilgour’s 1988 book Uneasy Patriots). “I think the West will have more confidence and hopefully more input into decision-making nationally…Canada will be a stronger nation, because we’ll be a stronger West.” So it has proved.

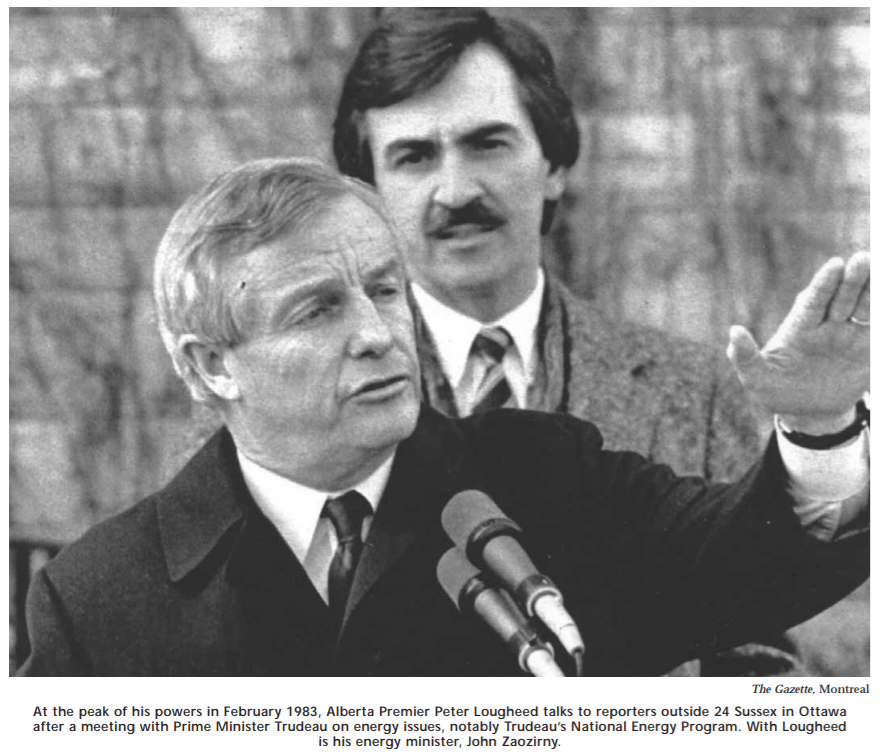

Lougheed’s determination to have the new West play a large national role was one of the pivots on which the great constitutional debate turned. Lougheed and Allan Blakeney had fought the federal government’s attempt to balance its own budget through imposing an export tax on oil in the 1970s and by a petroleum and gas revenue tax in 1980, known to this day in the West as the National Energy Program (NEP).

Lougheed and Blakeney made the case that Ottawa was not taxing Quebec’s exports of hydro, so why was it taxing resources in the West? (The Mulroney government, elected in 1984, repealed the NEP and since that time the federal government has not sought a share of oil and gas royalties.)

The energy battle led Lougheed to be a leader of the “Gang of Eight” premiers in opposition to Trudeau’s repatriation package. Lougheed especially disliked the regional “Victoria” amendment proposal, which gave vetoes to Quebec, Ontario and the regions of the West and Atlantic Canada. Instead, Alberta led the charge for a formula based more on provincial equality: most amendments would require the agreement of the federal government and seven of the provinces representing half the population — the 7/50 rule. It was Lougheed’s formula and the eventual constitutional deal was a swap — the provinces accepted the Charter of Rights and the federal government accepted Alberta’s amendment formula.

Peter Lougheed’s legacy is not only the head offices crowding into Calgary; it is also the enshrining of the provisions by which future generations of Canadians will decide their constitutional fate.

Allan Blakeney writes that “Premier Lougheed and Premier Davis of Ontario were both gentlemen, and able gentlemen. In my view, neither province has seen their equal to this date.” The experts consulted by Policy Options agree with Blakeney, as Bill Davis was a strong second to Lougheed as the best premier.

Davis’s electoral achievements are not as stunning as Lougheed’s — Davis’s majority in 1971 was followed by minority governments in the elections of 1975 and 1977, with a majority again in 1981, but four victories in four tries is still very impressive. Davis had inherited in 1971 a Tory dynasty that stretched back to George Drew in 1943, but Davis made that legacy his own, creating the fabled “Big Blue Machine.” Rosemary Speirs, of the Toronto Star, a newspaper not usually seen as a cheerleader for Conservatives, writes about the affable Davis, “His Tories proved adaptable, imposing restraint where once they had been expansive, while selling the voters the idea there was still no better place to go than Ontar-i-o. Davis’s image as a reassuring father figure for difficult times grew on the electorate.”

On the bread and butter issues, all the premiers highlighted in the survey have had to cope with the impact of the baby boomers, the “big generation.” Like a tidal wave, they engulf any of the public institutions they meet on their passage. None coped better than Bill Davis. As education minister in 1965, he created Ontario’s system of community colleges, and during his time as premier (1971-85) he funded and expanded this creation.

With Manning retired, in the 1971 election under the slogan “NOW,” Lougheed won 49 seats to the Social Credit Party’s 25 seats. In the 1975, 1979 and 1982 elections, he led the Progressive Conservative Party to landslide victories. In 1982, for example, he won 75 seats out of 79. This record is simply one of the most impressive in Canadian party history.

In 1984, in his last significant initiative as premier, he reversed a longheld position and announced that his government would extend funding to all grades of the Catholic separate school system. He told Eddie Goodman, a close adviser who feared alienating the Conservative Party’s Protestant base that “we cannot have a bifurcated system of financial aid any longer in Ontario…The fact is that almost half our students are in danger of receiving an inferior education and I don’t accept that.” Davis was the education premier par excellence! “Show me a good doctor, a good lawyer,” he told the Toronto City Alliance in 2003, “and I’ll show you a good kindergarten teacher, a good high school teacher and a good university professor. There is no more important commitment that a government can make than to educate. There really isn’t.”

Allan Blakeney, premier of Saskatchewan from 1971 to 1982, was not cut from the same heroic cloth as Tommy Douglas, the CCF-NDP icon, who introduced public medicine to Canada. But as a civil servant for the Douglas government, then a minister of health, and finally premier, Blakeney believed that Saskatchewan had exerted an influence out of all proportion to its size and that this influence was directed toward “making Canada the tolerant and relatively just society that it has become.”

Lougheed started with the premise that the free enterprise system would produce development and that this in turn would provide the necessary resources for social advancement. Blakeney began with a desire for social justice and was determined to show that a more caring society was also one that could thrive economically. The two men often ended up in the same place but they started from different ends of the political spectrum.

One of the achievements of Blakeney in advancing social democracy was fiscal probity. His government balanced its budget every year during his tenure, a record far superior to that of his Conservative Party successor. His government eradicated deterrent fees for medicare, established the University of Regina and created a successful Crown corporation in the potash industry.

But in one key priority area, Blakeney felt like “King Canute trying to hold back the tide.” Blakeney came to office determined to pursue a “vision of a new revitalized rural Saskatchewan consisting of the largest possible number of family farms.” His government introduced a host of initiatives — the Land Bank, supply management, Farm Start to encourage diversification and so on, but the economic forces leading to more mechanization and larger farms were stronger than any provincial initiative.

In another area, however, Blakeney was more aligned with the onrush of history. His government created the Department of Northern Saskatchewan to animate Aboriginal and Metis citizens to make life choices that would end dependency. It was rare for a government to try and implement Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals but Blakeney knew that the one-size-fits-all approach to public administration was not working for northerners. Blakeney identified early on that “the single greatest issue in Saskatchewan’s future is the development of relations between aboriginal and non-aboriginal people.”

Blakeney’s devotion to Aboriginal causes had a significant impact on the constitutional settlement of 1981-82. As the sides hardened on the Trudeau package, Blakeney kept lines of communication open with both camps. Though Blakeney eventually joined the Gang of Eight, largely because of his opposition to an entrenched Charter of Rights, Roy Romanow, his deputy premier, was given leeway to negotiate with Jean Chrétien, the federal minister of justice, and Roy McMurtry, attorney general of Ontario, to see if there were grounds for a compromise.

Blakeney himself spoke frequently with Lougheed and Davis. A new provincial position (not supported by Quebec) was put together in Blakeney’s suite at the Château Laurier during the evening of November 4, 1981, prior to breakfast with the Gang of Eight in the morning.

Bill Davis was also instrumental in the compromise. I was present at 24 Sussex on the evening of November 4, 1981, with Jean Chrétien and others to review the progress of the negotiations. Trudeau was noncommittal. He then took a call from Bill Davis at 10 p.m., who told the PM that he should compromise rather than fight a referendum. Following the call, Trudeau told Chrétien to see how many provinces he could get to sign on.

After the accord was signed on November 5, 1981, the debate was not quite over. When many women’s organizations objected to the fact that the notwithstanding clause would apply to equal rights, several of the premiers agreed to change this provision of the pact. Blakeney saw his opportunity: if the accord was to be opened up for women’s rights, he argued, why not for Aboriginals? He proposed a constitutional amendment to recognize treaty rights. Lougheed agreed, if “existing” was added to the section. So was born section 35, which says that “existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal people of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

Frank McKenna’s biographer, Harvey Sawler, describes McKenna as “the Lougheed of the East” and when McKenna surpassed Lougheed’s electoral landslides by winning every New Brunswick seat — 58 of 58 — in becoming premier in 1987, Lougheed called: “I wanted him to know I was distressed,” Lougheed joked. After three majority governments, McKenna left office in 1997 with an approval rating almost as high as when he became premier.

Rarely has New Brunswick, as a small province, made much impact on the national scene, but this changed with McKenna. McKenna had to deal with the emerging issues of debt and recession. He passed balanced budget legislation and achieved this goal before leaving office. If Davis was the “education premier,” McKenna was the “entrepreneurial premier,” personally visiting CEOs to persuade them to locate in his province and established a 1-800-McKenna phone line, where he would answer the calls of business leaders personally. He introduced New Brunswick Works to train long-term recipients of welfare. He was a business-oriented premier from a region that had traditionally had the reputation of relying excessively on government largesse.

If Saskatchewan led the way on social programs in the era of the CCF, New Brunswick under McKenna was the source of innovation as Canada grappled with the forces of globalization and the demise of the old social welfare Keynesian consensus in the 1990s. McKenna’s devotion to his home province was total: Jeffrey Simpson, the noted columnist who comments on national politics, wrote in January 2006 that “Frank McKenna had the Liberal leadership almost for the asking. Except that he didn’t ask.” This surprised many, but not me.

Years ago, Frank McKenna were students together at Queen’s. After a regular game of Thursday night baseball, we gathered to settle the problems of the world and our place in it. Ambitions were pretty standard as these things go — some wanted to be prime minister, others to head up UN development agencies, etc. (I wanted to play third base for the Expos, easily the least realistic goal of the lot). When we asked Frank what he planned to be, the answer came back instantly: “I want to be premier of New Brunswick.” He achieved that goal and, in so doing, put his province on the map and changed its self-definition.

Robert Bourassa just edged out René Lévesque for the fifth position as Canada’s Best Premier of the Last 40 Years. Once again the tortoise bested the hare. Bourassa won his first provincial election in 1970, was returned in 1973, lost to René Léveque in 1976, retired as leader of the Liberal Party only to return and win again in 1985 and 1989. L. Ian MacDonald captures this perseverance with his history of Quebec politics entitled From Bourassa to Bourassa. In general, our best premiers enjoyed strong support from their electorates. Not so Robert Bourassa. Although he won substantial majorities of seats, the Parti Québécois was always a formidable opponent and the national dream of an independent state of Quebec created a division in Quebec politics far more severe than in any other province. Bourassa’s reputation as a “trickster” (the title of Jean-François Lisée’s 1994 book) was necessitated by the juggling he had to do to stay afloat in a world of opposing demands by the federal government, the Parti Québécois opposition and Quebec’s vigorous civil society. Bourassa had the most difficult political challenge of any of our five top premiers.

Lougheed started with the premise that the free enterprise system would produce development and that this in turn would provide the necessary resources for social advancement. Blakeney began with a desire for social justice and was determined to show that a more caring society was also one that could thrive economically. The two men often ended up in the same place but they started from different ends of the political spectrum.

Abbé Sieyès, one of the chief theorists of the French Revolution, when asked about his greatest accomplishment said: “I survived.” Bourassa might have said the same. He had many accomplishments such as initiating the James Bay hydro project in 1971, but was cruelly tested by tragic events like the 1970 October Crisis. He came close to achieving the Meech Lake Accord in partnership with Brian Mulroney but his use of the notwithstanding clause to override the Supreme Court decision on signs gave his Meech opponents much ammunition.

He was a rational man in an emotional time. Before the provincial election in 1985, I invited him to my seminar at Harvard. He spoke expertly on his study of monetary policy in the European Union and how many of the dreams of the Parti Québécois were unattainable according to the laws of economics. He enjoyed the give and take with the professors, especially the economists, and was generous in answering the questions by his American hosts. A good man in a tough profession.

If politics is the art of compromise, Davis, Blakeney and Bourassa were masters of the trade. They understood their electorates, appreciated the motivations of their opponents and were creative in finding solutions to paper over the divisions and to keep things working. Frank McKenna was transformative in getting his province to think about itself in a very different way. During his time in office, New Brunswick was the place to go to see innovative public policy at work.

Peter Lougheed is the standard against which every premier in the country is measured. He transformed his province, and in so doing, he transformed the country. He was the premier in the last 40 years whose purposes ran most in tandem with the grain of history.

Photo: Shutterstock