It might sound like a trick question for Trivial Pursuit, and it is this: How many premiers in Canada have become prime minister? The short answer may seem surprising: only one, Sir Charles Tupper, and he served only a short time period in this august office, and his role as premier of Nova Scotia had little to do with his assuming the leadership of the Conservative Party. From before Confederation in 1867, Tupper was a close friend and confident of Sir John A. Macdonald, and he had served as minister in numerous portfolios in the federal government. Tupper also had been High Commissioner to the UK after a dispute with John A. (curiously, he also was minister of finance in 1887-88) without surrendering his post in London). Tupper was seen as a natural successor to John A., and after Macdonald’s death in 1891, a succession of leaders floundered, and the party and cabinet pressed Tupper to return. He became prime minister in May 1896, only to face election defeat to Wilfrid Laurier’s rising Liberal Party. He stayed in Ottawa for four years as Opposition leader, then returned to London, where he died in 1915.

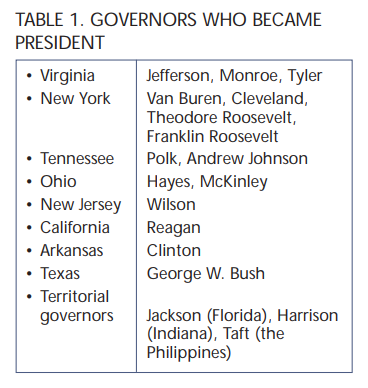

The fact that premiers haven’t climbed to what Disraeli called the “top of the greasy pole” may seem a true oddity of the Canadian political landscape in a federal system, where many provinces are proportionally bigger than US states. Indeed, Canadian political history stands in stark contrast to the US system, where 18 governors have become president, and 16 presidents, including the present incumbent, were US senators (see table 1). Why the difference? In general, most US states have budgets much smaller than the economies and budgets of the biggest Canadian provinces, although several presidents, including Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, were governors of very large states, California and Texas. Governors gain executive experience and they learn to work with both sides of the political aisle. More recently, US governors on the rise have taken on national roles, including as spokesmen for all US governors on such issues as education, infrastructure and health, gaining widespread media exposure, financial campaign support and clever media use of the incumbent’s weaknesses — Ronald Reagan’s attacks on Jimmy Carter, or Bill Clinton’s laser beam attacks on economic policies and the foreign policy forays of the two George Bushes.

There are factors why governors have an inside edge on the way to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The US election system is actually 50 state elections, because the tortuous Electoral College determines who becomes president, and many states are safe elections either for the Democrats (e.g., New York and California) or for the Republicans (e.g., Texas and Utah). Indeed, recent national elections for president show that the actual swing states are quite few, especially Ohio, so despite widespread national campaigning, presidential campaigns are really tied to the swing states and the US primary system to seek a party leader is dedicated to finding a candidate who can win the swing states. In theory, at least, governors are a natural fit.

This US model is in sharp contrast with the parliamentary system, with the modern version of party discipline, highly organized political parties and the special role of the elected caucus as the front line system of checks and balances. Indeed, most Commonwealth prime ministerial leadership races date from the model used in Britain. Historically, the key deciding actors are the monarchy, the elected caucus and the party at large. One might argue that Britain has changed the least among Commonwealth countries, and Canada is the most advanced, even Americanized, in how to choose a party leader.

Even in the 20th century, British party leaders came not from the party at large, but from their support in the caucus, elected members of the House of Commons and caucus leaders in the House of Lords. Winston Churchill — owing to his trenchant criticism of various policy positions and more directly to party leaders like Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain — was chosen as leader by the triumvirate of Chamberlain, Lord Halifax and Churchill. This was because Halifax was in the House of Lords, not the Commons, an unlikely situation for a wartime prime minister. More recently, Margaret Thatcher’s downfall as prime minister, however much disguised as caucus and cabinet solidarity, came from her loss of real authority in her cabinet, and John Major assumed the role as party leader and prime minister. All done in a leadership putsch in 24 hours!

Until the late 20th century, at a superficial level, Canadian party leadership models emulated the British system, with some differences. Clearly, the Crown played almost no role, direct or indirect, even when the governor general was a British citizen. (Some did influence policy direction.) The Liberals were the dominant party, ruling in Ottawa for most of the 20th century with a carefully calibrated rotation of francophone and anglophone leaders. Starting in 1919, the Liberal Party actually changed leaders only six times (1919, 1948, 1958, 1968, 1984 and 1990), and cabinet insiders had a huge strategic advantage because the new leader would immediately become prime minister. Public displays of openness and democratic rule were political slogans for what was a closed leadership model of the national governing party.

Canadian political history stands in stark contrast to the US system, where 18 governors have become president, and 16 presidents, including the present incumbent, were US senators.

Jean Chrétien, also serving as Opposition Leader, won his first majority in 1993. Indeed, in the Liberal Party, sitting cabinet ministers as leaders-in-waiting account for the long Canadian experience where leaders don’t come from premiers’ offices. Only Lester Pearson became prime minister after serving as Opposition leader, and it took two defeats, in 1958 and 1962, to gain the prime minister’s top job in the East Block, where the PM’s office was then located.

Clearly, the other parties had tried a different model to break the electoral stranglehold of the mighty Liberal fortress in the two largest provinces, Ontario and Quebec, with enough swing ridings elsewhere to gain a comfortable majority. This pattern of Liberal rule in Ottawa cultivated a truism of political science in Canada that the real checks and balances come from provinces that elected a government of a different party stripe than the government in Ottawa. As they used to say in Quebec: “Bleu à Québec, rouge à Ottawa.” They said the same thing in Ontario during the 42-year Conservative reign from 1943 to 1985, which pretty much coincided with a Liberal hegemony in Ottawa.

Like many truisms, it has an air of truth, but there are as many examples with the opposite position: elect a government that works closely with our cousins in Ottawa. In recent years, for instance, there were seven provinces with a Progressive Conservative Party banner during Brian Mulroney’s huge 1984 majority. Jean Chrétien’s Liberal government in Ottawa had Liberal governments in Ontario, Quebec, BC, New Brunswick and PEI. Even today, with a majority Conservative government in Ottawa, four provinces have governments of the same political stripe.

In short, sitting premiers or past premiers face huge obstacles on the national scene. One obvious reason is that the role of premier forces the incumbent to take a “me-too” advocacy role for their province, often using Ottawa or neighbouring provinces as a punching bag to gain more provincial advantages. Quebec has long played this advocacy role, not only in constitutional fights with Ottawa, but on issues of reducing interprovincial trade barriers, energy policy against Newfoundland and Labrador, even on US-Canada free trade in the 1988 election, when Ontario’s premier, David Peterson, and PEI’s Robert Ghiz tried to play the traditional nationalist card in favour of anti-free trader John Turner.

A second, more subtle reason is the format of leadership selection. In the 19th century, the two main parties, MacDonald’s Conservatives and the Liberals choosing Laurier, followed the British tradition of choosing their leaders from members of the caucus. This old-boy system often favoured not the elected members of the caucus, but peers from the House of Lords, a practice followed by the British Conservative Party until Douglas Hume faced defeat by Labour’s Harold Wilson in 1964. Today, it is inconceivable that a member of the House of Lords would lead a political party in Britain, the very reason why Lord Halifax didn’t become prime minister in May 1940, when Neville Chamberlain lost real authority in the House of Commons, and Winston Churchill assumed the vital role as prime minister. Ironically, it was only late in the war that he became leader of the Conservative Party itself and faced defeat in the election of 1945.

The first modern convention in Canada when party members, not caucus supporters, chose the leader was the 1956 Conservative Party leadership convention. Thanks to new forms of media, particularly television, this Ottawa convention served as more than a leadership race: it became a recruitment vehicle for the party, an astonishing new pulpit for the new prairie populist and a rallying cry for a national party stranded in the political wilderness, not only out of power in Ottawa since Bennett’s demise in 1935, but with few Conservative governments in the provinces — none in Atlantic Canada, zero support in Quebec and little backing in western Canada. Only Ontario stood as a bulwark for the Conservative Party, which had an implicit bargain: change leaders, not parties, a formula not unlike what has just happened in Alberta. In 1956, not too surprisingly, there were no Conservative premiers who offered themselves as a candidate for the national party, because there were only two Conservative premiers, one in Ontario, who preferred incumbency, and one who just got elected, Hugh John Flemming in New Brunswick. More to the point, the two previous national leaders, John Bracken and George Drew, had been premiers of Manitoba and Ontario and lost federal elections in 1945, 1948 and 1953. At that time, the Canadian political landscape smacked of Liberal Red from sea to sea.

This US model is in sharp contrast with the parliamentary system, with the modern version of party discipline, highly organized political parties and the special role of the elected caucus as the front line system of checks and balances.

As a result, there were only two opportunities for a sitting premier to lead a federal political party, with a remote chance of becoming prime minister. On both occasions, in 1967 and in 1983, that opportunity was the leadership race of the Progressive Conservative Party. Both races had a former prime minister wanting to reclaim his party’s mantle. Both lost. In both cases, there was a party outsider, both wanting to become leader and prime minister — Dalton Camp, party president, in 1967, and Brian Mulroney, in 1983, a failed candidate in the leadership race in 1976 and never elected to the House of Commons.

These two races form an important lesson for political aficionados of all parties but they also explain much about the evolution of Canada’s political system. The leadership races in 1967 and 1983 forever closed the backroom choices of party elites, lessened the role of insider caucus favourites and allowed the party to elect members from every riding in Canada, thus greatly diminishing the role of former elected officials, members of Parliament and senators. Indeed, starting with the 1956 leadership convention, and continuing to this day for all parties, the role of elected youth as delegates and university campus clubs became a powerful force in the party, reflecting a new demographic that US candidates like the Kennedys first cultivated (and candidate Barack Obama perfected, using the tool of social media), and became a source of ideas, recruitment, party staff and policy networking.

Various accounts have been written of both leadership races, especially a brilliant, inside view in a McGill University master’s thesis by Michael Vineberg, “The Progressive Conservative Leadership Convention of 1967.” In that race, the leadership battle between Manitoba’s sitting premier, Duff Roblin, and Nova Scotia premier Robert Stanfield was a case study in why premiers face huge obstacles, not only to win the leadership race but to win a national election. By most standards, Duff Roblin was the favourite, well known on the national stage, fluently bilingual and very popular in Quebec, and an assumed favourite successor in western Canada to the irascible John Diefenbaker. Robert Stanfield, scion of the wealthy Stanfield family in Truro, Nova Scotia, was unilingual, knew little about national issues, but was immensely popular in his native province. Indeed, he entered the race after winning another huge majority in Nova Scotia. Dalton Camp, who ran his provincial campaigns and his leadership race, once said that Stanfield was a son of a bitch to get elected, but once in power, he would be there forever.

Both premiers became leadership candidates but from very different positions. Stanfield was the most reluctant, personally favouring Roblin because he was bilingual and he could unite the fractious Diefenbaker element in the party. Roblin wanted to run, despite government problems at home, and he was not clear about who would enter the race, making him appear to some supporters as too indecisive. His problems became worse because of a little-known meeting in June 1967 in Winnipeg with Dalton Camp. At this secret meeting, Camp offered his help with Roblin’s leadership campaign and the national election to follow, but he was given a deadline of July 10. Roblin, worried about adverse publicity, kept this session secret except for close confidants, but waited past the deadline. Roblin also ignored his supporters’ desire for a large roll-out agenda. Camp returned to Nova Scotia, offered the same support to Stanfield, but implied strongly that Duff Roblin would not be a candidate.

Thus persuaded, Stanfield announced his candidacy a week later, on July 19. Roblin, caught by surprise, tested his own support in southern Ontario and Montreal, but decided to wait. For his part, he did not want to be seen as the candidate of choice for Dalton Camp and his followers, a widespread group assembled for his leadership for presidency of the PC Party against Arthur Maloney in a contentious fight the previous November. True, while Roblin thought that being seen as too close to Camp would alienate Diefenbaker loyalists, he was also persuaded that being a “reluctant” candidate would win a huge following in the party at large, on the assumption that a lead on the first ballot would lead to a winner on the last ballot.

Roblin and his followers also didn’t realize, until too late, that the leadership campaign wasn’t about the national media or about how many party brass or caucus members were on side. It was a delegate race, riding by riding. Despite Stanfield’s terrible media interviews, or even smaller campaign appearances, he travelled the country meeting delegates one on one. His campaign was run from Toronto, close to the convention site at Maple Leaf Gardens, and there was a separate campaign organization for convention week. Camp and his followers, shrewd operatives like Eddie Goodman, Finlay MacDonald, Norm Atkins, Jean Wadds, Lowell Murray and a team of young university recruits, but including caucus supporters, cultivated their national tentacles, including with other leadership campaigns, especially that of Davie Fulton. By the time the convention opened to the national media spotlight, the Stanfield campaign was operating on all cylinders. The convention went five ballots, but Stanfield led Roblin on all five by a comfortable margin. Stanfield lost three elections, in 1968, 1972 and 1974, to a new force in Canadian politics, Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

Stanfield was replaced in 1976 by Joe Clark, who beat Trudeau in 1979, only to lose power on a budget vote, and Trudeau, Lazarus-like, returned to power in February 1980. The Conservatives returned to their fractious party ways, and at the national convention in Winnipeg, January 1983, even though he won a support of confidence vote by 66.9 percent, Joe Clark stunned the party by calling for a leadership race in June 1983 (in part because he knew how weak his real caucus support had become). That spring, two premiers, Peter Lougheed of Alberta and William Davis of Ontario, were huge media favourites, supported on paper by regional groups, by certain caucus supporters, by Bay Street and the regional media, as well as by various sections of the party. But both decided in the end, despite soundings of their staff and caucus supporters, not to become leadership candidates. For both, it was a game of chicken: one would run only if the other ran.

Several members of Clark’s cabinet decided to enter the race, hoping to bring unity to a deeply divided caucus and party. As noted, Dalton Camp and his celebrated Big Blue Machine again had their favourite candidate in place, Ontario Premier William Davis. The only problem was that this candidate, Premier Davis, was not sure of his own standing across the country, and he knew first-hand its fatal weaknesses among French Canadians at large and in Quebec in particular, and his public criticisms of John Crosbie’s 18-cent gasoline would not go down well in western Canada or with John Crosbie and his followers.

In Alberta, Premier Peter Lougheed’s winning formula for elections made him a natural media darling, and despite Joe Clark’s Alberta roots, many political operatives in western Canada saw the Alberta premier picking up a huge delegate count outside western Canada. But these premiers also knew personally that behind the scenes, another candidate had devised his own winning formula for the leadership convention. Unlike in 1967, and with the lesson he learned from 1976, Brian Mulroney knew that becoming the secondchoice preference was the key to winning a multicandidate convention. Lougheed became a quiet supporter, and Mulroney was careful never to attack William Davis, the Ontario Conservative Party or their supporters, meanwhile slogging it out with Joe Clark for delegates in Quebec and across the country. Mulroney emerged victorious, winning the leadership race on the fourth ballot against Joe Clark. Despite taking over a fractious caucus and a party divided, 15 months later he won the largest electoral victory in Canadian history.

The lessons from the leadership races show that a sitting premier, even from a very large province or one with strong regional support, is unlikely ever to win a national leadership race, let alone win a national election. Federal issues are national in scope, but increasingly they are international and global. It takes hard work, travel and prodigious industry to learn the substance and nuances of federal issues, and that leaves little time to cultivate a national following from the incessant demands of the premier’s office. No majority election wins can come from a regional base only, so outsiders to Parliament (Brian Mulroney was an exception, cultivating a national Rolodex from birth and active in politics since his university student days at St. Francis Xavier) or successful premiers face massive electoral barriers. And it remains today an open question whether being a successful governor leads to the keys of the White House.

Photo: Shutterstock