Unlike most advanced industrialized countries, Canada does not have a national child care program. As a result, child care across the country varies considerably. The provinces and territories have their own rules and policies, each according different weight to the role of governments, commercial child care operators and parents. There is a wide range of programs and services with differences in standards, quality and fees depending on available resources and political will in each province. Quebec is the only province where child care policy provides for regulated, subsidized centre-based care.

The OECD report Starting Strong II ranked Canada last among 14 countries in spending on early learning and child care programs. As well, UNICEF’s report The Child Care Transition: Innocenti Report Card 8 concluded that Canada met only one of 10 benchmarks in setting minimum standards for early childhood education and care programs in the areas of quality, access, financing and policy. However, according to Statistics Canada there has been an increase in the employment rate of women with children in the past three decades. In 2010, the employment rate for women with children under six years was 66.9 percent, up from 31.4 percent in 1976. Notwithstanding the trend, some mothers do not work. For some women, this is a personal choice, while for others the key issue is unavailability of affordable and reliable child care. According to the Childcare Research and Resource Unit, in 2008 there were regulated spaces for only 20 percent of young children in Canada, despite the fact that more than 70 percent of Canadian mothers are in the paid labour force.

This article begins with an overview of child care policy in Canada and then reviews the programs in Alberta, Manitoba and Quebec. Based on this analysis and in light of the significance of government funding of child care for women’s labour market participation and the well-being of children, it is argued that greater governmental intervention and support are required.

In addition to being a liberal welfare state where child care is often market-based, Canada is a federation. The federal, provincial and territorial governments all share responsibility in providing benefit programs and services for child care. Publicly funded child care includes programs and services that are funded and regulated by government and offered at a low cost to parents.

The federal government plays a direct role in funding early childhood programs on First Nations reserves and for immigrants, refugees and the Armed Forces. Apart from that, its role is limited to providing tax credits, child benefit programs and transfer payments to provincial governments. The provinces have the responsibility for legislating standards with respect to quality of child care services such as staff-to-child ratios, health and safety standards, and early childhood educators’ credentials, among others.

The Child Care Expense Deduction, established by the federal government in 1972, allows a single parent who works or the lowest income earner in a family to deduct the cost of nearly any form of nonparental care (up to a limit of $7,000 for a child under 7 and $4,000 for a child between 7 and 16 years) from taxable income. The Harper Conservative government, elected in 2006, is opposed to a national child care program. Its emphasis is on parental choice, traditional child-rearing arrangements and gender equity. It introduced the Universal Child Care Benefit, which provides $100 a month to families with children under the age of six; this is considered taxable income for the lower-earning spouse.

At present, two federal initiatives provide funding to the provinces for regulated child care: the Multilateral Framework Agreement on Early Learning and Childcare, which promotes services to children under age six by providing funds directed at improving quality, affordability and accessibility of regulated care; and the Childcare Spaces Initiative announced in the 2007 budget. In response to the needs of families, the Child Care Spaces Initiative provide incentives to businesses, communities and nonprofit organizations to create up to 25,000 child care spaces each year. These initiatives provide $350 million and $250 million, respectively, to provinces annually through the Canada Health and Social Transfer. Under the Early Childhood Development Initiative beginning in 2001-02, $500 million is also provided annually to provinces and territories to invest in healthy pregnancy and infant care, early development and child care programs.

There is also the Canada Child Tax Benefit, which is a tax-free monthly payment available to eligible Canadian families to help with the cost of raising children under age 18. In addition, there is the policy on maternity and parental leave, which is paid through the Employment Insurance program; it is a contributory fund financed by both employers and employees.

In Alberta, child care is mainly market-based; the state plays a minimal role. According to Statistics Canada, in 2005 Alberta was the only province where the number of children aged 0 to 5 had increased since 1999. Yet it had the smallest proportion of children in daycare. At 64.9 percent, the labour participation rate for mothers in Alberta was also the lowest.

Manitoba’s approach is primarily nonprofit, and fees are provincially set and not determined by the market. According to Early Years Study 3, in 200910, 95 percent of early learning and child care centres in Manitoba were nonprofit. However, there is less than one child care space for every six children in Manitoba; this gap is wider for infants and school-aged children from rural and northern communities. In 2008 the Government of Manitoba announced its five-year strategy, Family Choices: Manitoba’s Five-Year Agenda for Early Learning and Childcare. This included the creation of 6,500 new spaces, conversion of surplus school space to child care, development of an age-appropriate early childhood education and care curriculum, increased training and access to service for diverse cultural communities and increasing wages and benefits for staff by 20 percent.

In 1997, the Government of Quebec announced a new family policy. The policy phased in affordable child care by setting a standard rate of $5 a day; this was increased to $7 a day in 2004. The fee is paid by parents, regardless of their employment income, for full-time daycare of up to 10 hours a day. In order to fund the program, subsidies to parents for daycare fees were eliminated, parents could no longer claim any child care expense deductions and all the public funding was provided directly to regulated child care providers. Since the introduction of the program, there has been a high demand for the low-fee spaces, and the program has not been able to meet the demand.

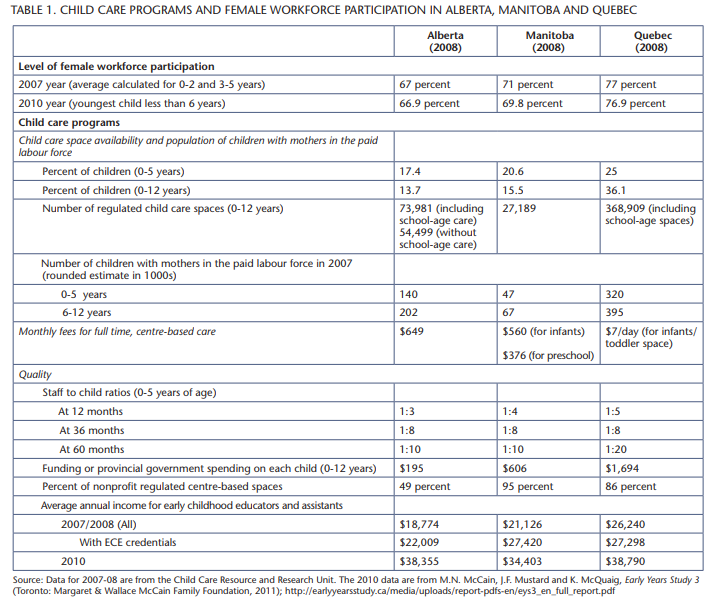

In 2008, Quebec had the highest percentage of child care space availability for both 0-5 and 0-12 year age groups, at 25 percent and 36.1 percent, respectively, while in Manitoba the rates were 20.6 percent and 15.5 percent, respectively. The rates in Alberta were the lowest, at 17.4 percent and 13.7 percent; at $649 a month it had the highest fees for provincially approved child care. Quebec’s fees were the lowest at $7 a day, while Manitoba’s set fees were $560 a month for infants and $376 a month for preschool children. In Manitoba, 95 percent of regulated centre-based spaces were nonprofit, compared with 86 percent in Quebec. In Alberta, only 49 percent were nonprofit. Quebec was the highest spender, allocating $1,694 to regulated child care for each child. Alberta was the lowest, spending $195 per child, while Manitoba spent $606 per child for 0-12 years of age.

Quebec’s early childhood educators and assistants had the highest salaries, $26,240 per year in 2008; Manitoba’s were at $21,126, and Alberta’s at $18,774. By 2010, these salary levels had increased to $38,790 in Quebec, $34,403 in Manitoba and $38,355 in Alberta. Alberta stands apart from other provinces due to a combination of low spending and high fees, even though, since 2008, 20,000 additional child care spaces were added by the Government of Alberta, surpassing the goal of 14,000 spaces (for additional information on the programs in the three provinces, see table 1). In sum, Quebec and Manitoba have been making the most progress in the area of child care due to the provincial governments’ intervention to ensure low or provincially set fees, reasonable quality and funding (although there is still a lack of regulated child care spaces).

Parents have the responsibility of ensuring that children receive optimal care while governments also have a responsibility to provide access to resources and opportunities to assist parents in contributing to the overall well-being and development of our youngest citizens.

In 2007, Quebec had the highest percentage of mothers in the workforce at 77 percent, followed by Manitoba at 71 percent and Alberta at 67 percent. These remained about the same in 2010. Although the proportion of women who were employed and had preschool-aged children has grown, they are still less likely to be employed than women with school-aged children or women without children. Statistics Canada reported that in 2009, 66.5 percent of women with children under six were employed, compared with 78.5 percent of those whose youngest child was aged six to 15. About 80.4 percent of women under age 55 without children were employed, compared with 72.9 percent of women with children under 16. This suggests that child care or schooling outside the home has a positive influence on female labour market participation.

Child care has been and remains a challenging issue in Canada. Not only is it a political matter, with Canada being a liberal regime and a federation with a division of powers, but there are differing social beliefs about families and children and a range of views on child care provision. Some parents may want more publicly funded child care services, but many also want the opportunity for one parent to be able to stay at home and raise their preschool children without sacrificing employment earnings — a finding from The Future Families Project: A Survey of Canadian Hopes and Dreams by sociologist Reginald Bibby from the Vanier Institute of the Family.

The current child care policy of tax credits and allowances does not sufficiently meet the needs of parents with young children. It does not help create child care spaces, and the lack of available, affordable and high-quality child care will remain a problem. Leadership and intergovernmental cooperation are needed in order to make more publicly funded child care available. The provinces have legislative authority over child care services; however, funding is required from the federal government or the provinces to be able to provide and strengthen child care.

More government intervention and support are essential in funding child care services, whether they are universal or targeted. Along with direct funding, services should be publicly managed and have assured operating funds and provincially established rates and fees. Parents should share the cost, which should be reasonable and affordable, as in Quebec. In addition, a maximum fee can be set, as in Manitoba, for consistency, quality and accountability from all care providers.

Further research is needed for a cross-country comparison of all the provinces’ and territories’ child care policies and how they affect female labour force participation. According to the OECD report Female Labour Force Participation: Past Trends and Main Determinants in OECD Countries, child care alone does not determine labour force participation of women; other factors need to be considered, including the level of female education, labour market conditions, leave provisions and cultural attitudes. Therefore, it is important to examine a range of factors and barriers to maternal employment in order to understand more fully how child care policy in Canada influences female labour force participation.

Achieving more publicly funded child care or a national child care program will continue to be a struggle. However, it is not impossible; there needs to be stronger social solidarity, determination, good governance and political will. Parents have the responsibility of ensuring that children receive optimal care while governments also have a responsibility to provide access to resources and opportunities to assist parents in contributing to the overall well-being and development of our youngest citizens.

Photo: Shutterstock