As part of an in-depth look at the policy priorities of Canadians, the IRPP partnered with Nanos Research to examine the views of Canadians on many of the challenges we face as a nation. Two broad forces — the importance of issues closest to the day-to-day lives of Canadians, and the greater focus of elected officials on issues with possible solutions, may be the hallmarks of the public policy environment for the foreseeable future.

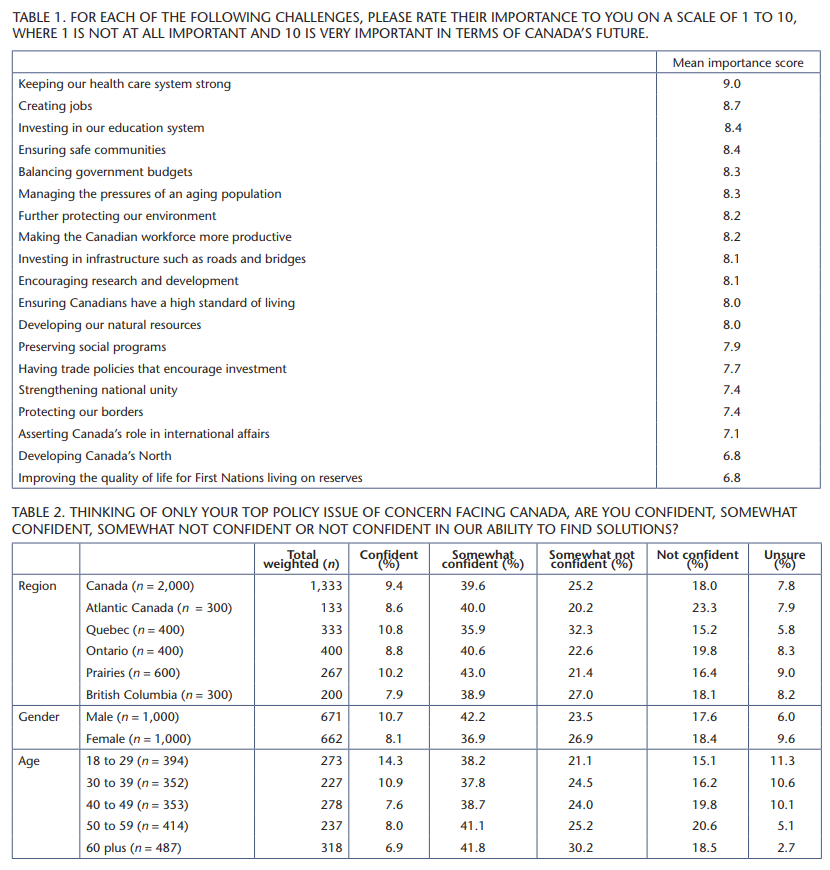

While a majority of Canadians thought that all of the public policy issues tested were important, two clear clusters of opinion emerged. We asked Canadians to rate the importance to Canada’s future of a series of policy challenges, on a scale of 1 to 10 (where 1 was not at all important and 10 very important; see table 1). The policy issues closest to the day-today lives of Canadians were more likely to receive higher importance scores than those that were distant. Keeping our health care system strong held the top spot, with a resounding 9 out of 10 in terms of importance. Regardless of the pull and tug between the federal and provincial governments over the Health Accord, and other discussions about the future of health care for Canadians, health care stands at the top of the importance hierarchy. Whether it is access to general practitioners in rural Canada or emergency room wait times in cities, this one issue has a very high level of importance that cuts across region, gender and generation.

Not surprisingly, in an era of economic uncertainty, creating jobs was very important, rating 8.7 out of 10. Although Canada has weathered the global recession better than most countries, it is clear that the petro-economy, while smoothing the turbulence, has produced a certain economic asymmetry. The Prairie provinces remain economic drivers, while the manufacturing sector in Central Canada continues to stall. Even with this asymmetry, a majority across Canada, and in the economically hot Prairies, rated creating jobs a 9 or 10 out of 10 in importance. Rounding out the top four issues of importance to the future are investing in education (8.4 out of 10) and ensuring safe communities (8.4 out of 10).

What is interesting is that all of these issues are quite close to the day-to-day lives of Canadians. Can my mother get her hip replaced? Can I keep my job? Will our children have the education they need to prosper? Are we safe in our communities? These are the types of questions that are preoccupying Canadians.

Those issues that seemed the most distant to many respondents improving the quality of life for First Nations living on Reserve, developing Canada’s North and asserting Canada’s role in international affairs -— all received lower importance scores (6.8, 6.8 and 7.1 out of 10, respectively). Perhaps, in terms of public opinion, being out of sight is also being out of mind.

Individually, the issues all scored as important. But when respondents were asked to name the most important issue, health care and job creation clearly dominated. Asked to choose the most important issue, keeping our health care system strong was identified by 24.9 percent of Canadians as the top issue, followed by creating jobs, at 19.7 percent, and balancing government budgets a distant third, at 9.7 percent.

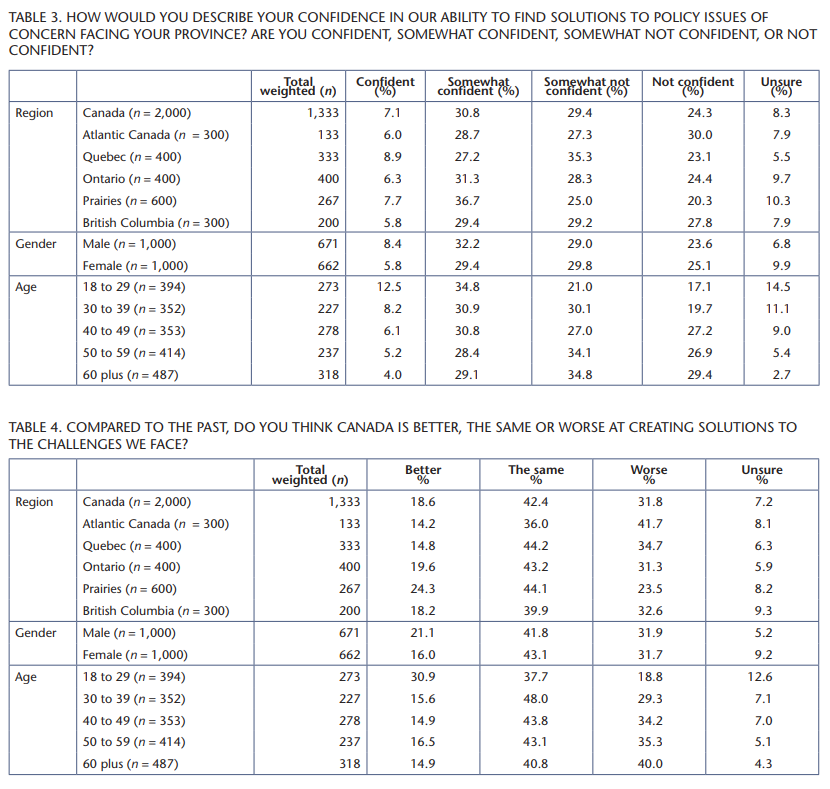

Canadians were generally split in their level of confidence in terms of our ability to solve national or provincial policy issues of concern. On the national level (table 2), Canadians were twice as likely to be not confident (18.0 percent) as confident (9.4 percent) in our ability to solve policy issues of concern. On the provincial front (table 3), the confidence deficit increases from a two-to-one to a three-to-one ratio. Only 7.1 percent of Canadians were confident in our ability to find solutions to top policy issues facing their province, compared with 24.3 percent who were not confident. For both of these measures the rest of Canadians were in the mushy middle — either somewhat confident or somewhat not confident.

A generational pattern did emerge on the provincial and national levels: younger Canadians, although still a minority, were comparatively more confident in our abilities to solve problems compared with older Canadians.

Asked about whether we are better or worse now at creating solutions, Canadians were more likely to believe that we were worse (31.8 percent) than better (18.6 percent) compared with the past (table 4). The one outlier on this measure was Canadians from the Prairies (Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta). Just as many Canadians in that region (24.3 percent) thought we were better, compared with those who thought we were worse (23.5 percent) at finding solutions to challenges compared with the past. It’s likely that the economic mood is a key lens many look through to assess our ability to find solutions.

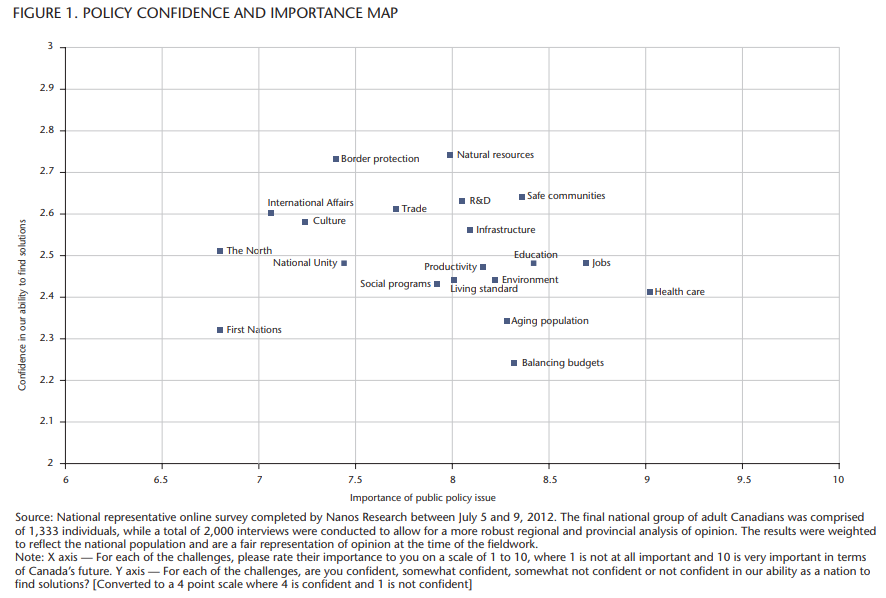

Mapping the data on the importance of an issue as well as those on the confidence in our ability to find solutions provides an interesting view of the relationship and clusters of opinion.

To do that we created the “Policy Confidence and Importance Map” (figure 1 below). At a glance, one can see the relative positioning of issues on the grid in terms of importance (X axis) and confidence (Y axis). The exhibit in this article zooms in on the right part of the map because realistically all the issues were gauged to have some sort of importance to Canadians.

A number of things stand out. Health care is clearly the most important issue, positioned as it is the farthest to the right, but the confidence in finding solutions is lower than for a number of other issues. A cluster of social issues such as aging population, social programs and living standards are reasonably important, but confidence in finding solutions to them is low.

Interestingly, balancing budgets is important, but it received the lowest comparative confidence score even though federal and provincial governments have balanced the books at one point or another. This suggests that the short-term optimism on balanced budgets is low.

The most significant finding is the cluster of issues near the top in terms of confidence — natural resources, border protection, safe communities, research and development (R&D), trade and international affairs. The importance of these issues varies, but they are the ones in which Canadians have a comparably higher degree of confidence in our ability to find solutions.

One could argue that many of these issues seem to be aligned with the current priorities of the Harper government — energy and the oil sands, border security, crime and trade.

This brings into focus the factors that have a major impact on the policy development process. Consider this: If our elected politicians are interested in their own political ends, they will tend to focus on issues that Canadians believe can be solved, while not focusing on issues that Canadians believe are more difficult to solve.

The challenge is that many public policy pressures that demand attention are complex and distant, not just in terms of geography, but also in time and money. Canadians have a lower confidence in our ability to find solutions to the issues of our aging population and the living conditions of First Nations on reserve.

Does that mean that our officeholders should not explore solutions? I think not. This study does bring into clarity one factor — we must understand the views of Canadians, and how these views are likely to influence elected officials as they look to balance political expediency with more complex policy imperatives.

Photo: Shutterstock