When it comes to jobs, western Canada gets a lot of glowing attention. Much of it is justified. With labour markets operating at or above full employment and in the midst of an extended commodities cycle, it is undeniable that Alberta and Saskatchewan have been significant contributors to Canada’s economic performance over the last decade. Between 2000 and 2013, growth in total employment was nearly 40 percent in Alberta, which is approximately double that in Canada as a whole. As Livio Di Matteo, a Lakehead University economist, blogged in March on Worthwhile Canadian Initiatives, Alberta’s employment “juggernaut” is the Canadian economic “story of the 21st century.” And the Globe and Mail’s John Ibbitson echoed that view in a column, also in March, declaring that Alberta, and by extension the West, is now “the beating heart of Canada’s economic future.”

Versions of this refrain, and its corollary about challenging economic realities everywhere else in the country, are often repeated. There has been an obvious shift in economic activity, population and political influence toward the western provinces over the last decade. But the underlying question is whether national labour market realities are, in fact, diverging in ways that create regional inequalities that should concern us. In a highly regionalized economy such as Canada’s it bears asking: How do regional labour markets differ from each other?

Apart from their structures, how do regional economies vary when it comes to landing a job or the incentives to get one? Is western Canada the “story” behind the changing dynamics of jobs and income across the country?

To properly examine these questions we need to take a much longer view than the last 12 months, or even the last five years. Given the cyclical nature of commodities (important to western Canada) and longer-run changes in goods production (important to central Canada), we need to look at change over many decades.

The charts in the following pages begin to tell an interesting story.

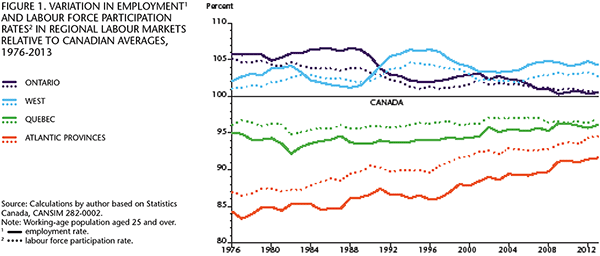

In figure 1, I plot the changes in two key indicators of labour market performance — the labour force participation rate (the share of the population employed or looking for work) and the overall employment rate (the share of the population that is employed) — across regions, and how they have changed over time relative to the national average. I have defined the working-age population as being 25 and higher in order to really focus on the period when people pursue career-related work. For purposes of comparison, I have subdivided Canada into four regions: the four western provinces, Ontario, Quebec and the four Atlantic provinces.

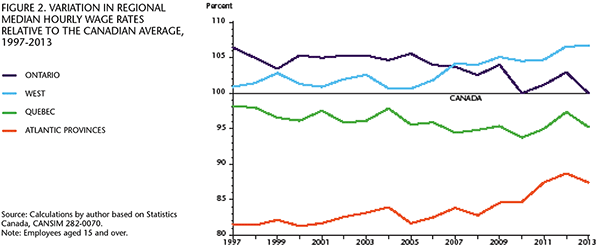

In figure 2, I compare changes in median hourly wages relative to the national average across these regions. Because of limitations in the data, we can only look at the period since 1997. The trend lines are broadly the same in the two charts.

The shifting pole-position between Ontario and western Canada is plainly obvious and of no surprise to anyone. However the following much more important observations can also be made from this simple analysis:

- Atlantic Canada, while still considerably below the national average over the full period, has seen significant improvements on all the metrics relative to the other regions of the country.

- The gap between the top and bottom performing regions appears to be shrinking, suggesting we are seeing less variance than in the past.

For all we hear about the surging economic performance of western Canada and the need to find supporting labour and investment to encourage growth, the greatest relative improvement in labour force performance over the last four decades has actually been in some of the poorest provinces in the Confederation. Clearly, much of this shift began after the mid-1990s and is likely a response to major structural reforms in employment insurance during that time. But this is not the full story. The persistence of this upward trend over the long term also suggests that this is about more than the offshore oil development in Newfoundland and Labrador.

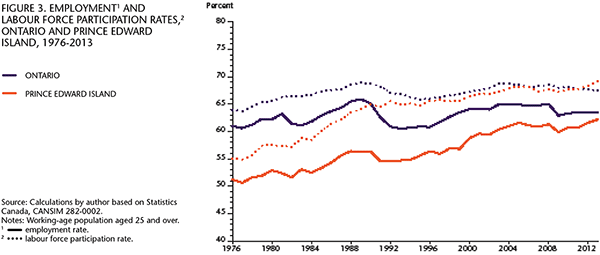

The significance of the regional shift in Atlantic Canada is particularly striking when we compare Prince Edward Island and Ontario over the same period. As I show in figure 3, the labour force participation rate of PEI, the smallest province in the country and one that is so dependent on seasonal employment, has moved from being approximately 9 percentage points below Ontario’s in 1976 to being higher than Ontario’s by nearly 2 full percentage points. The closing of the gap between the largest and smallest provinces is equally noticeable on the employment side.

The extent of Atlantic Canada’s improvement is remarkable for many reasons. The fact that more residents in Atlantic Canada are joining the labour force and finding employment represents real hope for a region that has come to be viewed as a source of labour for other parts of Canada.

Considering that the region has historically had an older population and slower population growth than the rest of Canada, the Atlantic provinces’ experience may also have lessons for the rest of the country as it begins to deal with similar challenges over the next two decades. If provinces that are further ahead on the curve of population aging have been able to adjust to some of these pressures while still raising their game and closing some of the gap with the best performing regions, the rest of the country should take notice.

That’s a good news story for the economic union, and it should remind us that we are in fact more than a collection of regions with distinct cultural and economic realities. While the challenges facing Ontario and Quebec should concern us all, and western Canada is indeed an ever more important engine of growth, we can’t lose sight of what’s happening in the aggregate. Over the long term, the top-line data suggests we are seeing greater convergence of the national average across all regions, as well as faster wage growth and better employment prospects in some poorer provinces.

And it means that to understand how to deal with future labour market challenges, policy-makers must start to look East just as much as they now look West.

Photo: Shutterstock by Ronnie Chua